With a ‘Goodbye, Denver,’ City Loses Longtime Voice

- Share via

DENVER — In a city focused on the future, Gene Amole was the elegant spokesman for the past.

Change made him cranky. Sprawl made him cross. As a columnist for 24 years at the Rocky Mountain News, he played the role of nostalgic old-timer in a town swarming with newcomers.

He could be stubborn, contrary, out of step with the times. But his abiding decency and generous spirit made him the dean of Denver journalists, the city’s answer to Herb Caen or Mike Royko.

The typical Amole column was a diatribe against the taxpayer-funded airport, or a screed against taxpayer-funded stadiums, or a wistful paean to the old days, when Denver’s air and water were clean, its politics dirty. (Colorado’s governor in the 1950s pulled a gun on Amole, a memory he treasured.)

Change was Amole’s subject, his constant foe, until October, when he encountered one change he couldn’t fight: His own mortality. In a memorable column that caught even his colleagues by surprise, the 78-year-old columnist announced that he was dying and that he would cover his last days as a story.

For months Amole wrote about the pain of death, the humor of it, the inconvenience. He rambled and rhapsodized and wept on the page, and described the dying of the light. During one 17-week span he wrote a column every day the newspaper published, outworking colleagues a third his age.

His chronicle of a death foretold drew thousands of e-mails and letters and phone calls, and his long-standing connection with the city grew even deeper.

On Monday, the chronicle ended. One day after Amole died of “multi-system failure,” the News published his farewell, one last column Amole had left in reserve.

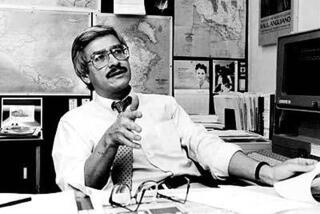

“Goodbye, Denver,” read the front-page headline, above the familiar photo of Amole, hand to his temple, smiling wistfully. It was a sterling piece of journalism, more for what it was than for what it said. Even in death the consummate newspaperman had managed to make one last deadline.

On Friday, capping a week of remembrance, Denver honored Amole by doing what it seldom does, what Amole was forever telling it to do: It paused. Hundreds gathered in Civic Center Park for a reading of Amole’s finest columns, an unusual tribute for a man who didn’t consider himself a great writer.

Tom Gavin, a friend and former managing editor of the News, told the crowd that Amole would be sorely annoyed to see them all there. “If ever there was a man noisily intent on slipping quietly away,” Gavin said. “Yet here we all are, trampling his careful plans.”

He closed with a fitting send-off for a curmudgeon: “May flights of angels sing him to his rest,” Gavin grumbled. “Whether he likes it or not.”

Amole was born in Denver, and seemingly born to newspapers. He learned to read by studying the News through his grandfather’s magnifying glass.

In his inaugural column, and often thereafter, he spoke of the newsroom as his paradise, his home, his destiny. “Everyone has to be somewhere,” he wrote in 1993. “My somewhere is the newsroom.”

That may be why he treated the News as he treated people, with a cherishing tenderness, an old-fashioned courtliness. Sometimes, referring to the News, he would adopt a reverent tone normally reserved for his wife, Trish, his four children and his grandson.

Long before he walked into the newsroom, however, Amole was already a household name in Denver. Popular disc jockey, pioneering TV personality, wealthy businessman--and, above all, war hero.

Joining the 6th Armored Division when he was barely out of his teens, he fought in many of the epic battles of World War II, including the Battle of the Bulge. War formed him. War hardened his head and softened his heart. War made him permanently wistful, and writing a column helped him work out why. Readers often held their breath as he struggled with the poignancy of his war memories and tried to translate their emotional aftermath.

In 1989, nearly 44 years after the day he came home, he wrote about the scene:

“Mom, Pop and Grandpa were waiting for me at the top of the passenger ramp at Denver Union Station. I tried to hug them all at the same time and still keep my duffle bag on my shoulder. My mother was crying as she counted the battle stars on my ETO ribbon. I was alive and home. The war was over and I wanted nothing more than to put it behind me forever.

“It wasn’t long, though, before I began to realize that it would never be over for me.”

The young veteran suffered flashbacks and nightmares and insomnia, which lasted for decades. He also endured bouts of survivor’s guilt, as one of only three young men from his neighborhood who returned from the battlefields. He never forgot the five who didn’t.

Still, the war columns were rare. He much preferred writing about autumn, Dvorak or dinner. He could make a column from a beautiful sunrise and the smell of fresh-brewed coffee. He was a renaissance man, equally able to discuss French impressionists, Colorado poet laureate Thomas Hornsby Ferril or the proper way to cook a meatball. In one of his best-known columns he divulged his secret recipe for Thanksgiving stuffing, mixing the ingredients with references to Lao-tse and Gertrude Stein.

“The authenticity of Gene Amole really spoke to people,” said Patricia Raybon, associate professor of journalism at the University of Colorado-Boulder. “When we talk about writing a personal essay, the name Montaigne always comes up, and one of the things about the Montaigne model that Gene practiced is an element of self-abrasion, a kind of dismissive quality about yourself and your own importance.”

Read one after another, Amole’s columns could also be viewed as a series of 600-word love letters to a vanished Denver. For a 1991 column, he simply walked downtown, sat on a bench and closed his eyes, recalling how everything looked and smelled half a century before. He could remember every bar, every brothel, every barbershop, and he evoked them all with a mapmaker’s precision.

“I can still hear streetcars clanging their way from one intersection to the next,” he wrote. “Joe ‘Awful’ Coffee, owner of the Ringside Lounge on lower 17th Street, would shadowbox with you as he escorted you to a booth for dinner.... Clark’s Drug Store in the Albany poured the richest, thickest chocolate shakes in Denver. The ‘Mayor of 17th Street’ was Danny Abeyta, whose shine parlor was right next door. Every morning, bookies, horse players, stock brokers and other gamblers lined up for a Kiwi luster on their Florsheims while Danny’s wife blocked Stetsons at the rear of the store.”

Some read Amole’s columns as the diary of an honest man’s life. So it made perfect sense that he would attempt an honest diary of dying--though a few colleagues cringed, fearing readers would recoil.

Instead, the response was “almost overwhelming,” said News editor and publisher John Temple. “Wherever I went in this city, I heard, ‘Thank you for letting Gene Amole write this column.’”

Most of the final columns were written from home, in the study where he would die. No longer strong enough to visit his beloved newsroom every day, he made one last trip to the newspaper, in December, for a ceremony in which Mayor Wellington E. Webb officially renamed the street outside the News: Gene Amole Way.

Dapper in a tan hat and trench coat, Amole choked up as he told the crowd, “I’ll always be here,” then walked off on the arm of his daughter, a former reporter at the News.

Many who gathered Friday at Civic Center Park agreed that Amole would always be in the News. Some said he would also always be in their lives.

“It kind of kept my dad alive for me to read his column,” said Evelyn Drake, a retired teacher, wiping tears from her eyes.

But the columns became something more, she added, when she realized each one might be the last.

“He made us realize that dying is a part of living,” she said. “There’s nothing to be afraid of, but you have to face these things. There’s nothing to fear, but you just have to help those you love get through it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.