Cigarettes, Greed and Betrayal: An Insider’s Saga

- Share via

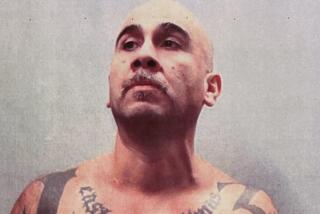

Les Thompson was a self-made man. He grew up poor in a small town in Ontario and got no further than high school. Still, he fashioned a nice career in the cigarette business, rising through the ranks at the Canadian arm of R.J. Reynolds.

In the early 1990s, he took on a big and risky assignment: helping the company gain a foothold in Canada’s exploding market for contraband cigarettes. As a regional field manager for RJR-MacDonald Inc., he supplied cigarettes to U.S. distributors, who had them smuggled back into Canada across the St. Lawrence River to avoid Canadian taxes.

With Thompson’s help, the company amassed more than $600 million in revenue and more than $100 million in profit from contraband sales, Canadian authorities have alleged.

Thompson’s superiors rewarded him with a promotion and lavish praise. Then, some of the distributors were arrested. And they began pointing fingers at him.

He pleaded guilty to money laundering and spent two years in a U.S. prison. He became the most notorious figure in the smuggling boom that prompted Canada to rescind a steep tax increase meant to curb smoking.

An obscure unit of R.J. Reynolds pleaded guilty to a smuggling-related offense and paid $15 million in fines. But the company emerged otherwise unscathed. It portrayed Thompson as a rogue employee who had strayed from its law-abiding corporate culture by, among other things, accepting improper gifts from the distributors.

Though he was hauled off in disgrace, Thompson didn’t really go away. Released from prison in January, he has emerged as a key figure in civil suits and criminal investigations into the global trade in contraband smokes. He has been cooperating with investigators from the United States and the European Union.

“I’m looking forward to going to court and telling the story under oath,” he said in an interview.

Information provided by Thompson was central to a lawsuit by the Canadian government that sought to recover $1 billion in lost taxes and law enforcement costs from RJR. The case, dismissed last year by a U.S. court, is expected to be refiled in Canada.

Thompson has also told his insider’s story to Canadian investigators in a probe that is expected to result in criminal charges against tobacco firms, officials and suppliers -- possibly including his former superiors at RJR-MacDonald.

Thompson, who traded a good career and the promise of a bountiful retirement for a rap sheet, said he has never stopped wondering: Why only me?

Interviewed at his home in Canada, Thompson portrayed himself not as a renegade but as an obliging cog in a wheel of corruption. There was no way a mid-level executive could fill multimillion-dollar orders for cigarettes without the approval of superiors, he said. Prosecutors on both sides of the border have said the same thing.

Representatives of R.J. Reynolds referred questions about Thompson to Japan Tobacco International, which acquired Reynolds’ international business in 1999. A spokesman for Japan Tobacco, Guy Cote, said the company could not comment because of the Canadian investigation. But he cautioned against taking the word of “a convicted felon” who took kickbacks.

If Canadian authorities bring new charges against tobacco executives, Thompson could be a key witness -- a situation he would relish.

“I’m not asking anyone to pass me a handkerchief here,” he said. “But it’s important to me that the story doesn’t end with Les Thompson.”

Diverted Exports

Experts say a quarter to a third of cigarette exports worldwide winds up getting diverted from legal channels and smuggled across international boundaries. This cheats governments of tax revenue and encourages smoking by keeping supplies of cheap cigarettes on the market.

In addition, cigarettes have been used around the world as common currency for laundering profits from drug trafficking and other crimes, allegedly with the collusion of tobacco companies, according to a suit filed last month by the European Union against R.J. Reynolds. The company called the charge “absurd.”

As for their purported role in cigarette smuggling, tobacco companies have vigorously denied responsibility, saying they sell their products legally and can’t track them through every twist and turn of the distribution chain. At the same time, the firms have used smuggling as a powerful argument against cigarette tax hikes.

This is the scenario that played out in Canada, where the government waged war on smoking by imposing tax increases that nearly doubled the price of a pack.

In the early 1990s, cigarette exports to the United States from Canada rose more than tenfold. Americans had not suddenly developed a taste for Canadian brands. The Canadian cigarettes, exported tax-free to U.S. distributors, were smuggled back into Canada, without the baggage of more than $3 a pack in federal and provincial taxes.

The tobacco companies themselves didn’t do the smuggling. They supplied middlemen, who supplied the smugglers, court records show. Insulated by intermediaries from the dirty work, tobacco executives described theirs as a “gray market” business, Thompson recalled.

The hub for this traffic was the Akwesasne Mohawk Indian Reservation, which straddles the border in upstate New York and southern Ontario, stretching across a narrow reach of the St. Lawrence River that can be crossed by small boats throughout the year.

In 1989 and 1990, the reservation was convulsed by violence involving feuding tribal factions and police. To cool things down, police reduced their presence. For cigarette smugglers, it was wide-open turf.

A Lucrative Enterprise

As the contraband market exploded, RJR-MacDonald’s American parent, RJR Nabisco, was staggering under $26 billion in debt resulting from a leveraged buyout by a group of investors. It needed all the help its far-flung units could give. Yet of the three big cigarette makers in Canada, RJR-MacDonald was a distant third behind Imperial Tobacco Ltd. and Rothmans, Benson & Hedges Inc. If those competitors prevailed in the contraband market, the gap could widen.

From his sales office in a Toronto suburb, Les Thompson saw the problem firsthand. His otherwise-loyal secretary smoked Players, a rival brand, for a simple reason. At the bingo hall, where cigarettes were cheap, Players was the only brand in stock.

“In defense of Reynolds, they didn’t invent that business,” Thompson said. “It wasn’t a new concept by any stretch of the imagination.”

Thompson said that in March 1992 -- on orders from Ed Lang, then chief executive of RJR-MacDonald, and Stan Smith, then vice president of sales -- he had lunch at the Como Restaurant in Niagara Falls, N.Y., with three men who would become his biggest customers. (Lang, Smith and their lawyers declined to be interviewed.)

The three, Larry Miller and brothers Robert and Lewis Tavano, had colorful pasts. Robert Tavano, a former Republican Party chairman of Niagara County, went to prison in the 1970s for stealing county insurance premiums. Lewis Tavano, a sports bookmaker in Las Vegas, had been indicted with several others, including former Buffalo crime boss Stefano Maggadino, in a gambling case -- though charges were dismissed because of an illegal wiretap.

The men had formed a partnership, named LBL Importing (for Larry, Bob and Lewis), to sell Canadian cigarettes to Indian traders on the Mohawk reservation. They were moving large volumes of Rothmans cigarettes to warehouses there, Thompson recalled. And they were sure they would have similar success with Export A, RJR-MacDonald’s top brand.

Thompson said he reported to Smith that this looked like a great opportunity.

“The mind-set was that you’ve got an underperforming business unit,” he said. “Here were some people who were making very strong statements that they could deliver the types of volumes that were expected of the operation.”

Approval of new customers at RJR-MacDonald was usually a long, laborious process, but LBL was fast-tracked, according to Thompson and the Canadian lawsuit.

Within weeks, the cigarette maker and LBL were doing a brisk business.

About the same time, the lawsuit said, RJR-MacDonald took further steps to penetrate the black market.

Early in ‘92, the Canadian government briefly imposed a cigarette export tax as an anti-smuggling measure. Anticipating the move, the company shifted two production lines from its Montreal factory to a cigarette plant in Puerto Rico.

For the next several years, the offshore plant made Export A’s for the contraband market. According to Thompson and the Canadian lawsuit, when the Puerto Rican plant opened, Miller and the Tavanos were among the guests given tours.

RJR-MacDonald also contracted with a North Carolina factory to produce Export A “fine cut,” the loose tobacco used to hand-roll cigarettes. The fine cut also was smuggled into Canada, according to the government lawsuit.

Thompson said that on numerous occasions, his superiors reassured him that he was not putting himself in legal peril. He said a lawyer who sat on the RJR-MacDonald board told him: “It’s a gray business. It’s a loophole. It’s not pretty, but we’ve got to be there.”

Thompson said his superiors provided more than $1 million a year for high-end junkets for the black marketeers and company executives.

He said the special customers were taken bonefishing in the Bahamas, to luxurious golf clubs and to the major league baseball World Series in Toronto -- always flying first class and staying in the finest digs. They were frequent guests at the Sonora Island Lodge, a $1,000-a-day fishing resort on a remote island off the coast of British Columbia, according to Thompson and the lodge’s owner at the time, Michael Gallant.

“They loved to fish, they liked to party,” Thompson said. His superiors saw it as “an opportunity to keep the momentum going and satisfy the appetite of the customer,” he said.

Thompson said he took part in about 15 of these junkets -- and felt as if he had entered a parallel universe of the rich and famous.

He recalled a reception at a Formula One race in Montreal, where guests rubbed elbows with race car driver Niki Lauda. Thompson said he considered himself the kind of guy who should be sitting in the bleachers “with a hot dog and warm beer ... and here we are entertaining RJR’s gray marketeers in the paddock areas with awning-type suites.”

Though Thompson enjoyed himself, he said, he was somewhat troubled by the excess.

But he did not let this interfere with the business at hand.

“I bought into the program with little, if any, hesitation,” he said. “I wanted to do what’s expected of me, and I wanted to succeed.”

At the peak, Thompson said, RJR-MacDonald made a weekly profit of $1.2 million to $1.3 million from the contraband trade and saw an increase in its market share.

When a member of his sales team toured Akwesasne in 1993, the numbers told it all.

The salesman visited six tobacco warehouses on the reservation to see how stocks of Export A compared with those of rival brands. At all six warehouses, Export A volumes were as high as, or higher than, those of any of the competitors’ cigarettes.

“The availability of black market cigarettes ... in Canada has increased tenfold over the last two years,” the salesman told Thompson in a memo, a copy of which was obtained by The Times. The salesman described such cigarettes as “easily available at virtually every street corner to a hungry smoking population.”

By this time, contraband busts had become a staple of TV news -- the Canadian version of police pursuits on L.A. freeways. Thompson recalled two RJR-MacDonald vice presidents bantering as they watched a report of a seizure of rival brands. One of them teased Thompson about not having any “market share” in the bust, while the other quipped that Thompson’s customers were just better at not getting caught.

Even so, company executives feared embarrassment or worse if the footprints led to RJR-MacDonald’s door. So, Thompson said, they created a separate company to feed the contraband market. They called it Northern Brands International, and they located it far from Canada.

The company was incorporated in Delaware at the end of 1992 and headquartered in Winston-Salem, N.C. It operated out of 401 N. Main St., the Art Deco office tower that also served as headquarters for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. and R.J. Reynolds International.

Officers and directors of the fledgling firm included at least two senior vice presidents of the international unit.

Early in 1993, Thompson and a colleague, Peter MacGregor, were sent to Winston-Salem to run NBI -- Thompson as head of sales and MacGregor as finance director. MacGregor and his lawyer declined to be interviewed. Along with a third employee, they constituted the entire work force.

At his send-off in Canada, Thompson’s colleagues gave him a special going-away gift -- an Indian headdress.

The contraband business grew even bigger under NBI.

In 1993, 5 billion of the 8 billion cigarettes produced by RJR-MacDonald were sold through NBI to black-market suppliers and then funneled back to Canada, according to Canada’s lawsuit.

In October 1993, Ed Lang, the head of RJR-MacDonald, touted NBI’s performance at a briefing with the chief executive of RJR Nabisco, the Canadian lawsuit said. According to the lawsuit, Lang said NBI’s quarterly earnings were $58 million, prompting the RJR Nabisco CEO to ask how the pipsqueak firm could possibly bring in so much cash.

Before Lang could respond, the CEO said he remembered that NBI was in the “feather” business in upstate New York -- a reference to the Indian connection -- the lawsuit states.

Although not named in the suit, RJR Nabisco’s CEO at the time was Charles Harper. Harper, 75 and retired, said in an interview that he could not recall such a conversation.

“This was a straight-up kind of company,” Harper said from his home in Omaha. “Our deal was that we were not going to do anything that was illegal.”

Always the solid performer, Thompson suddenly became something of a hero. Now, he said, Lang called him “partner,” while colleagues greeted him as the “Indian Trader” or yelled war whoops when he passed.

He was promoted to regional director and soon after, in June 1993, got a letter of thanks from RJR-MacDonald President Pierre Brunelle. “Your hard work and dedication to the company have made a significant contribution to the success we have realized over the years especially in recent months,” Brunelle wrote.

That December, at the company Christmas party at Casa Loma, an ornate castle-turned-banquet-hall in Toronto, Thompson and MacGregor were flown in from Winston-Salem as special guests. As they entered the room, Thompson recalled, they received a standing ovation.

Incentives for Crooks

The tobacco companies blamed the rampant smuggling on the Canadian government, saying excessive taxation had created irresistible incentives for crooks. But a 1993 letter that surfaced years later in U.S. tobacco litigation suggested that the companies knowingly exploited the black market.

The letter was from R. Don Brown, chairman of Imperial Tobacco, Canada’s largest cigarette maker, to his superior in London, Ulrich Herter, managing director for tobacco at Imperial’s parent, British-American Tobacco.

“As you are aware, smuggled cigarettes due to exorbitant tax levels represent nearly 30 percent of total sales in Canada, and the level is growing,” Brown wrote. “Although we agreed to support the Federal government’s effort to reduce smuggling by limiting our exports to the U.S.A., our competitors did not.

“Subsequently, we have decided to remove the limits on our exports to regain our share of Canadian smokers.... Until the smuggling issue is resolved, an increasing volume of our domestic sales in Canada will be exported, then smuggled back for sale here.”

With the market drowning in contraband cigarettes, the Canadian government in 1994 adopted the tax-cutting fix that cigarette makers had relentlessly promoted. On top of slicing 50 cents from the federal tax, the government offered to match additional cigarette tax rollbacks by the provinces.

These measures slashed cigarette taxes by $1.92 a pack in Ontario and $2.10 in Quebec. Smuggling sharply declined.

For tobacco companies, whose products were suddenly legally available at a deep discount, it was a tremendous victory. Public health groups cried foul, arguing that the tax cuts over time would re- sult in thousands of additional smoking-related deaths. Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chretien voiced bitterness too.

“The Canadian manufacturers have benefited directly from this illegal trade,” he said. “They have known perfectly well that their tobacco exports to the United States have been reentering Canada illegally.”

Meanwhile, in the U.S., cigarette makers made certain the lessons of Canada would not be lost on citizens or tax-minded politicians.

Soon after the Canadian rollback, a group with a public-interest veneer -- the National Coalition Against Crime and Tobacco Contraband -- set up shop in Washington, D.C. It was underwritten by R.J. Reynolds.

The coalition commissioned studies to draw press attention to the link between cigarette taxes and smuggling. Its top consultant and spokesman was Rod Stamler, a former officer of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who had previously done a report for Canadian cigarette makers attacking the Canadian taxes.

In August 1994, with a tax hike proposal pending in Congress, Stamler issued a new report, saying the measure could “provide organized criminals with one of their most attractive profit-making opportunities since Prohibition.”

This would be the industry’s mantra.

In April 1998, Steven F. Goldstone, chairman and chief executive of RJR Nabisco, led Big Tobacco’s campaign against a sweeping tobacco control bill that included a record increase of $1.10 in the federal cigarette tax.

In speeches to such groups as Wall Street analysts and the National Press Club, Goldstone warned that the tax, if approved, would unleash a wave of smuggling like that seen across the border.

“If Washington creates a raging black market for cheap cigarettes on street corners and in schoolyards, the people will be furious,” Goldstone said in one speech. “And they will ask, just as they did in Canada: ‘How did we get ourselves into this terrible mess?’ ”

The tobacco bill was defeated.

A spokesman for Goldstone, who is no longer with the company, said the executive had no idea when he gave those speeches that an RJR subsidiary “would wind up ... involved in a plea related to that type of activity. He was outraged.”

A Business Collapses

To this point, authorities had not accused RJR of involvement in the Canadian smuggling. That was about to change.

Undercover agents on both sides of the border had infiltrated some of the contraband rings. In June 1997, Larry Miller, the Tavanos and 18 employees and associates were arrested and charged in Syracuse, N.Y., with numerous smuggling-related crimes. All 21 defendants would eventually plead guilty to reduced charges.

Within days of the arrests, Les Thompson got a phone call from a special agent with the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, inviting him for a chat. Thompson recalled the agent saying: “Everybody we’re talking to are offering to make a deal, and they are pointing a finger in your direction.”

“My heart was just racing like a madman,” Thompson said. In retrospect, he added, his big mistake was in not accepting the invitation and telling what he knew from day one. Instead, he kept quiet and trusted the company to protect him.

Another shock came in August, when Thompson and his wife, Kathy, came home in Winston-Salem after a round of golf to find news crews parked on their lawn. Thompson’s name had surfaced in the New York smuggling case.

In September 1997, RJR International sent Thompson on temporary assignment, to conduct a marketing study in Florida. In reality, Thompson said, it was make-work meant to keep him off the public radar. He and his wife were put up in a south Florida resort condominium at company expense. Under other circumstances, this might have been the high life.

But Thompson was filled with dread, knowing his career -- and his freedom -- were in jeopardy.

“I was a nervous wreck,” he recalled. “People would slam car doors, and I would just jump off the curb.”

Still, it was comforting to know he had a rich and powerful company behind him, and top-notch legal talent in his corner too.

A diet of rah-rah speeches from company executives calmed Thompson as well. He was told that he had nothing to worry about, that if everyone stuck together it would all come out fine. At a meeting in Toronto in April 1998, Thompson said, Paul Bourassa, then general counsel of RJR International, told him: “The government’s saber-rattling.... Stand tall.... Nobody’s leaving the boat.”

Bourassa, now general counsel of Japan Tobacco International, did not respond to requests for comment.

On Dec. 22, 1998, in federal court in Syracuse, Northern Brands left the boat -- pleading guilty to a single smuggling-related tax offense. It was the first time a major tobacco company or affiliate had been convicted of a federal crime. In exchange for the plea and $15 million in penalties, federal authorities agreed not to bring charges against the big names of the corporate family: RJR Nabisco, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., R.J. Reynolds International.

But prosecutors said there was no question NBI had done their dirty work. NBI was established “with the understanding that there was money to be made by smuggling cigarettes back into Canada,” U.S. Atty. Thomas J. Maroney said.

For Thompson, who was portrayed in the NBI indictment as a key figure in the scheme, it was the beginning of the end.

Thompson began negotiating a severance with RJR and headed back to Canada. In February 1999, while waiting in a Canadian hotel for the furniture to arrive, Thompson got a call from U.S. Customs asking him to go to the border to sign for his things. Arriving at the Customs station, he was handcuffed, whisked off to jail and soon hauled to a lockup in Syracuse.

He faced two counts of laundering profits from the smuggling scheme. Facing a possible term of 20 years and a $500,000 fine, Thompson struck a deal. He pleaded guilty to one count, was sentenced to nearly six years in prison, fined $20,000 and ordered to forfeit more than $85,000 in gifts -- including cash, a used Cadillac and golf lessons he had accepted from Miller and the Tavanos.

The sentence permitted Thompson’s transfer in two years to Canadian custody, where he was likely to be paroled quickly.

RJR fired Thompson, taking away his pension and stock options that he says would have been worth several hundred thousand dollars. He had to tap his retirement account to pay legal costs and fines.

In a proxy statement filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the company sought to distance itself from him: “Employees are prohibited from engaging in smuggling or other violations of the law. No corporate policy can eliminate the risk that dishonest individuals, including company employees, will find ways to circumvent controls for their own personal benefit.”

At a court hearing in Canada in February 2000, Thompson pleaded guilty to Canadian charges and was sentenced to probation as part of an agreement to cooperate with authorities.

Canadian prosecutor Michael Bernstein told the court: “Mr. Thompson was not on a lark of his own here. He did not commit this crime by himself. His acts were part and parcel of a corporate strategy developed largely by senior executives who closely monitored and supervised his work. It was the companies who made the huge profits here.”

Then RJR-MacDonald lawyer Douglas Hunt addressed the court, making an unsuccessful request to file “a victim impact statement.” The company had “suffered physical or emotional loss as a result of the commission of the offense,” he said.

Thompson was sent to the federal prison at Butner, N.C., so he could cooperate with a federal grand jury in Raleigh investigating whether RJR had played a role in tobacco smuggling in Europe.

In prison, Thompson, a nonsmoker, found that the best way to cope was to exhaust himself in physical activity. As a younger man, he had been a distance runner, with a personal best in the marathon of 3 hours, 16 minutes. Even past 50, he was trim and fit.

In prison, everyone had a job, and Thompson became the leader of the aerobics classes. He impressed younger inmates with the number of chin-ups he could do.

Thompson also was named third baseman on the over-40 all-star softball team. His pride was tinged with anxiety, as he had won the position over a murderer known as “Hacksaw.”

Otherwise, Thompson read everything he could get his hands on, avoided the TV room, where the fights broke out, and dreamed of better days.

Taped to the refrigerator at the Thompsons’ home is a card Les sent from prison to wife Kathy. Along with two pictures -- of a hiker silhouetted against a snowcapped peak and a pair of kayakers on a down-river run -- is a handwritten note: “A few of the activities we will plan on my return.”

Starting Over

Thompson got out of prison in January and settled in a small Canadian town that he asked not be identified. Finding a good job is never easy at 55. And it doesn’t help if an otherwise-strong resume has a mysterious three-year gap.

“The whole stigma of what I’ve been through carries huge baggage with some of these companies,” he said. “You’re really forced pretty far down the food chain.”

Finally, in early September, Thompson landed a marketing job at a small company, making a fraction of the $111,000 salary he had earned during his best year at RJR-MacDonald. It was a great relief to be back at work and productive again.

“Different things happen to us as we’re growing up,” he said. “I got through it. I’ve got my family ... I’m a healthy guy, and I’m a much better per- son.”

No matter what he might do in the future, Thompson said, “I’m going to feel better about it than what I did for Reynolds.”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

The traffic in smuggled smokes

In the early and mid-1990s, billions of cigarettes were exported from Canada and then smuggled back in to avoid steep Canadian tobacco taxes. Here is how the process typically worked, according to Canadian authorities.

Step 1: Tobacco companies in Canada export cigarettes. Since the cigarettes supposedly will not be sold in Canada, they are not subject to tobacco taxes. The shipments go to free-trade zones in U.S. border areas.

Step 2: Distributors take possession of cigarettes and transport them to the Akwesasne Mohawk Reservation in upstate New York, where they are sold to members of smuggling rings who store them in warehouses.

Step 3: Smugglers transport the cigarettes across the St. Lawrence River on small boats.

Step 4: Contraband cigarettes are sold cheaply in bingo halls, stores and parking lots.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.