Idun Hopes Nobel Attracts Financing

- Share via

What is a Nobel Prize worth to Idun Pharmaceuticals?

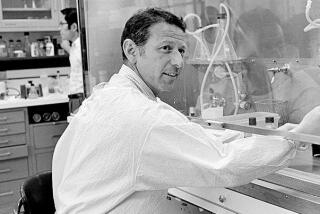

The small San Diego company has an exclusive license on the discoveries by Massachusetts Institute of Technology scientist H. Robert Horvitz, including his breakthrough work on the “cell death” gene that on Monday won the Nobel Prize in medicine. Horvitz co-founded Idun, named for the Norse goddess of eternal youth, in 1994 to transform his science into medicines for heart attack, stroke and cancer.

The company, with just 55 employees, is several years and many millions of dollars from delivering a drug to patients. Harnessing the biology that controls cell death into a single pill has proved extraordinarily difficult. Persuading investors to back a visionary but risky technology that only recently has received attention from big pharmaceutical companies has been just as tough.

The privately held company is preparing to close a round of financing that took six months longer than expected and values the company at one-tenth the amount it commanded in 1999. Idun lost 20% of its employees in the last year because of a salary freeze implemented to conserve cash.

The company hopes that the Nobel Prize will assist its fund-raising efforts. “With this level of validation, hopefully, they will pay attention and realize this may be really important,” said Chief Executive Steven J. Mento.

Still, there is evidence that even a Nobel Prize isn’t a sure bet in biotechnology, where it takes many years to translate a laboratory observation into a mass-produced drug. Colorado-based Ribozyme Pharmaceuticals Inc. is testing a drug that uses Nobel Prize-winning cell-replication technology, but the company is out of favor with investors. Its shares closed Monday at 33 cents on Nasdaq.

“It takes 10 to 15 years to go from cutting-edge research to drug development,” said John McCamant of the Medical Technology Stock Letter in Berkeley. “A lot of things can happen when you take a drug from the laboratory to the human body.”

Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis ended a collaboration with Idun in 1998 after the companies found that a drug that appeared to prevent brain cell death in the laboratory would not work in people.

Idun’s lead drug candidate is designed to prevent the death of cells damaged by liver disease. Mento said Idun chose liver disease because the company has the technology to direct cells to that organ. The drug is about to enter the second of three phases of human testing required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Idun, like many California biotechnology companies, was born of invention and frustration. Horvitz and co-founder John C. Reed formed the firm after big pharmaceutical companies rejected cell-death technologies as too risky.

“The Mercks, the Pfizers, they thought it was all too early stage, and they did not want to take the first steps,” said Reed, president of the Burnham Institute, a San Diego-based cancer research center. “It was really out of that frustration that we decided to seek more open-minded investors.”

The company has raised a total of about $75 million since its inception, with $15 million of that from venture capitalists and the rest from pharmaceutical companies such as Novartis.

Horvitz’s discovery of the cell-death gene anchors an intellectual property portfolio that includes 100 patents related to the mechanisms that cause cells to commit suicide. Though Horvitz studied a worm, humans have a similar gene that triggers production of an enzyme that causes cells to die.

Horvitz is chairman of Idun’s scientific advisory board and attends its board meetings, though he is not a corporate director. He belongs to a group of founders who will own less than 10% of the company when the latest round of financing is completed, probably before the end of the year.

Idun is using the technology in two ways. Relying on Horvitz’s expertise, it is developing drugs to halt the death of cells threatened by injury or disease. It also is developing drugs that hasten the death of cancer cells, Reed’s specialty.