Vaccines as a First Line of Defense

- Share via

ATLANTA -- Officially, smallpox strains exist only in the legitimate World Health Organization repositories of Vector in Novosibirsk, Russia, and the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. But the people most familiar with the disease say they almost certainly exist in other places as well. Intelligence reports place the virus at the Russian military laboratories of Sergiyev Posad and perhaps elsewhere in Russia. Many believe North Korea has stores of the virus -- perhaps alluded to in that nation’s announcement last week that it has continued to pursue nuclear weapons “and more.”

About Iraq’s bioweapons program there has been little but hints and rumors. Bioterror expert Michael Osterholm, formerly of the Minnesota Department of Health, reports that Jordan’s late King Hussein told him “on his deathbed” that Iraq has the smallpox virus. Laboratory equipment labeled “smallpox” was found in 1994 by United Nations Special Commission inspectors, although Iraqi scientists said the equipment was used only to prepare smallpox vaccine. They admitted, however, to working with camelpox, a related virus that can be used as a stand-in for smallpox in the laboratory.

A declassified 1994 U.S. intelligence report states that the Soviets passed “technology relating to smallpox and anthrax” to North Korea and Iraq. The author of that report, a former intelligence officer who wishes to remain anonymous, told me that he did not mean that the virus itself had been passed to Iraq; “they wouldn’t have done that,” he insists.

Maybe. But, in any event, all this is circumstantial evidence, reported in the press for years. Now there is reason to believe the Bush administration has new cause for alarm about smallpox and Iraq. This alarm, whispered about in high circles, has caused a major policy change, quietly implemented in the last couple of weeks.

Despite the clear risks of the live smallpox vaccine, the Bush administration is moving as quickly as supplies become available toward offering voluntary smallpox vaccinations to the entire country.

Whatever the government now knows or suspects, the threat is real enough to eliminate most informed opposition to rapid voluntary immunization. The CDC, which has long promoted a strategy of “ring vaccination” aimed at containing an epidemic after it occurs, has dropped its reflexive opposition to the idea of pre-attack vaccination.

Even Donald A. Henderson, director of the World Health Organization smallpox eradication campaign that eliminated smallpox from nature in 1977, who is a longtime opponent of mass vaccination, may be changing his position. He has publicly stated that the Bush administration, in which he is a top public health advisor, is “very worried” that Iraq has smallpox samples.

Peter B. Jahrling, a chief smallpox scientist for the Department of Defense, puts it more bluntly: “I think we’re nuts not to offer vaccination to the public immediately if we’re about to go to war.” Israel has already begun vaccinating emergency workers based, presumably, on intelligence estimates of its own.

There are still holdouts against offering the vaccine to all Americans. In last week’s issue of the Journal of the American Medical Assn., professor of pediatrics John M. Neff and his co-authors presented a new analysis of adverse reactions among 11.8 million people vaccinated for the first time against smallpox in the 1960s, before routine vaccinations ceased.

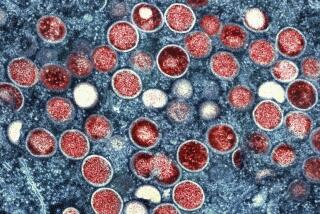

Smallpox vaccinations contain a live virus (vaccinia), which is closely enough related to smallpox that it confers smallpox immunity to anyone vaccinated. Most people have little or no adverse reaction to the virus contained in the vaccination, but some -- particularly those with weakened immune systems or even the common skin disease eczema -- can develop full-blown vaccinia infections from the injections.

Moreover, the virus can spread from person to person. Neff and his colleagues found that for every 100,000 vaccinations, there were between two and six instances of the virus spreading to unvaccinated people, and some of these transmitted infections were fatal.

Routine vaccination stopped in 1972 because scientists felt that the risks from the vaccine were greater than the threat of smallpox.

But in the eyes of the Bush administration, the threat of smallpox now outweighs the risk of vaccination, with its possible attendant liabilities of lawsuits and public anger. Would mass vaccinations actually protect us from whatever it is the Iraqis have? Jahrling says yes, that vaccinating even 60% of the population would dramatically curb the virus’ value as a weapon.

“There’s no point in launching a weapon that doesn’t have a target,” he says. Furthermore, “even if we don’t reach the entire population, significant herd immunity would blunt epidemic spread of the virus.”

But this assumes that what the Iraqis have is what Jahrling calls “your mother’s smallpox,” the virus as we knew it before its eradication. What if modern technologies have allowed Iraqi bioweaponeers to produce a new, modified form that would evade vaccine-induced immunity altogether?

Such constructs have been created using related viruses: An Australian team reported last year that it had inadvertently created a deadly altered form of the virus -- a chimera -- by introducing a gene for a mammalian immune protein, interleukin 4, into mousepox.

Among mice that were genetically resistant to mousepox and who were immunized with a weakened strain of the same disease, 60% (three of five) died after they were injected with the new chimera. This startling result -- a genetic modification to a virus that appeared to overcome vaccine-induced and natural immunity -- worried many experts, who feared that the same results could be achieved with the smallpox virus.

Furthermore, as I reported in this section a year ago, Sergei Popov, a former Soviet bioweapons researcher at the Vector Laboratory, hand-synthesized the DNA for a number of human immune chemicals in the mid-1980s, introducing it into smallpox vaccine and into mousepox as a stand-in for smallpox.

He had every intention, he says, of marching through all the interleukins, but he stopped after interleukin 2 when he left Vector. The technology to make smallpox chimeras with interleukins, therefore, has existed for a long time, and it is not unreasonable to suppose that Iraq could have this capacity.

But, as former Soviet bioweaponeer Igor Domaradskij puts it, “It is not so simple” to make a workable genetically altered bioweapon.

Attempts to repeat the Australian experiment with mousepox have been ambiguous. Mark Buller of St. Louis University replicated the experiment -- but he gave his genetically resistant mice stronger vaccine-induced immunity before infecting them with interleukin 4 mousepox. His mice did not die. “It’s one thing to engineer the construct,” says Buller. “It’s another to get the result you are looking for.”

We also don’t know what would happen if someone added interleukin 4 to smallpox. “The disease course of [smallpox] in man is totally different from [mousepox] in mice,” says Buller. We don’t even know what happens to a chimeric virus in a population: Would the added genes drop out, or would the disease fail to transmit at all?

Buller plans to test his construct’s staying power by introducing it into a mouse colony and letting it spread -- if it does spread. But even those results won’t mean much for smallpox, as the diseases are spread through entirely different routes.

“I don’t think any of these concerns should preclude mass vaccination right now,” says Jahrling. Chimeric viruses may represent a threat in the future, as science better understands how to make stable constructs that can spread.

It is possible that someday the smallpox vaccine may not be enough. We may need more sophisticated vaccines, or antiviral drugs, as a critical second line of defense. But until then, it would be very foolish not to protect against a real danger for fear of a chimerical one.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.