Corporation Oils Government Gears

- Share via

TURA, Russia — After a calamitous winter three years ago, Lyudmila Trippel thought she and her husband might leave this remote Siberian region where winter temperatures frequently plunge to minus 60 degrees.

That year, Trippel had to sleep wearing a winter overcoat because the district ran out of heating fuel due to cuts in federal subsidies.

Then, in early 2001, Yukos Oil Co. moved in, buying control of a regional oil firm that held licenses for huge but hard-to-access oil deposits. Months later, Yukos executive Boris Zolotaryov was elected governor. Thanks to tax revenue from Yukos and the company’s charitable donations, many towns and villages enjoyed satellite communications and Internet access. Trippel opened a grocery store here in Tura, the region’s capital, and as her customers prospered, so did she.

“I know the governor cares, and the governor is connected to Yukos,” Trippel said. “And I know my life has gotten so much better that I’m not planning to leave anymore.”

Once a place of bright hopes, the Evenk Autonomous District -- a region about the size of France and Britain combined -- is gripped by newer fears. Trippel, like nearly everyone here, is afraid that the good times may be destroyed by fallout from the October arrest of Yukos’ chief shareholder and former head, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who is in jail on fraud and tax evasion charges.

Khodorkovsky, a possible rival to Russian President Vladimir V. Putin, is expected to remain behind bars until after the March 14 presidential election.

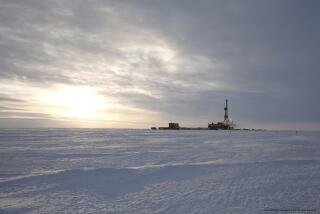

Located in the geographic center of Russia, Evenkia is a land of thick pine and birch forests in the south and tundra in the north, with oil, gas, gold and diamond reserves, and wildlife including bears, elk and reindeer. Its economic future depends on Yukos’ ability to pump oil. Many of the 16,600 people who live here fear that the Russian government will so cripple Yukos that the company will abandon the effort, returning Evenkia to destitution.

Without Yukos, “we would go right back to the Stone Age,” said Sergei Kogachyov, deputy director of the Evenkia telephone exchange.

*

Long Arm of Business

The strategy by major corporations such as Yukos to seize the reins of government extends beyond Evenkia. In the past few years, business tycoons or their close associates have become governors or district heads in a number of Siberian territories. Billionaire Roman Abramovich’s December 2000 election as governor of Chukotka -- the region across the Bering Strait from Alaska -- was another notable example.

Such positions have also been steppingstones to Russia’s parliament, which in addition to prestige carries the benefit of immunity from criminal prosecution -- a privilege that can be more valuable than money to people who became rich through corrupt privatization of state assets in the 1990s.

Some view the phenomenon as an effort to take political control of mineral resources. Others see a sincere attempt to improve the overall social and political environment for business and raise fellow citizens’ standard of living. Whatever their motives, the newly dominant businesspeople in such districts also take over the role of the central government -- from improving schools to saving reindeer.

During czarist and Soviet times, Moscow promoted the growth of settlements in Siberia and northern regions to reinforce Russia’s claim to these vast territories. Under the Soviet Union’s economy, with production decisions determined by central planning, it was expedient to run money-losing operations to achieve goals such as populating these areas and ensuring Moscow’s dominance.

Post-Soviet life remains enormously difficult in most of what Russians loosely define as “the North” -- the Arctic regions of European Russia and everything east of the Ural Mountains, home to about 11 million people.

During the past decade, many unprofitable factories and heavily subsidized settlements have been abandoned, with the central government subsidizing relocation. About 1.5 million people have migrated south or west from the most frigid areas.

“For a period of 10 years before 2000, nothing had been built here, nothing was repaired,” said Vladimir Odnolko, first deputy chairman of Evenkia’s Legislative Assembly. “Everything was standing still. Life was frozen. All the industries, all the social infrastructure, were dilapidated and out of order. That’s why additional funding was needed to stabilize the situation.”

The arrival of Yukos changed everything. The entire district became something of a company town. Taxes on Yukos’ operations allowed government spending to triple, improving the district’s sparse infrastructure.

Yukos also boosted education, furnishing local high schools with computer equipment and Internet access. The company also granted dozens of scholarships -- and paid transportation expenses -- for students attending university outside Evenkia. Various towns and villages received gifts of dental equipment from Yukos.

Asked at a Moscow news conference about the close relationship between the oil company and Evenkia’s government, Yukos financial director Bruce Misamore said that “there is a business rationale for anything we do in the regions.”

Anatoly Amosov, chairman of Evenkia’s Legislative Assembly, said that once elected, the new governor struck an agreement with the local government “that we would be rendering services to each other and do all kinds of favors.” Evenkia simply cannot get by without some outside help, he said.

“All the farms that existed in the district were planned to be money-losing, because of the high cost of production,” he said. “The government had to subsidize the production of meat or fish or fur or anything else.”

*

Indigenous Initiative

The Evenki people, who compose about 20% of the district’s population and give it its name, traditionally herded reindeer, hunted, trapped and fished. Some still do, though the old ways of life have mostly faded into memory.

“With help from Yukos, Evenkia’s government has made some efforts to fend off the complete destruction of traditional life, which is inescapably linked to reindeer herding,” said Vice Governor Nina Kuleshova.

“There is even a proverb in Evenkia: ‘Without reindeer, there can be no Evenki,’ ” continued the vice governor, who is half Evenki and half Yakutian. Two decades ago, there were 30,000 reindeer in Evenkia, but by the end of the 1990s their number had plummeted to about 2,000, and “nobody was happy with it,” she said.

Early this year, 1,000 reindeer were purchased in the neighboring region of Yakutia but were too weak to be herded many hundreds of miles to their destinations in Evenkia, she said. Aside from frozen rivers that are kept open with snow plows and then used by trucks in the depths of winter, there are no roads that cross the region. Yukos flew in the herd as far as Tura, then the animals walked the rest of the way on the river ice to reach their spring grazing pastures, she said.

Now Evenkia’s reindeer population is back above 4,000, and the old occupation has a future, she said.

There were trade-offs. Evenkia’s indigenous reindeer were big and wild, with a tendency to run away on their own, while animals from the new stock brought in from Yakutia are smaller and tend to herd together, she said.

There is no particular conflict between the oil industry and reindeer herding because the activities take place in separate areas, but there has been some disruption to the hunting of fur-bearing animals, she said.

Odnolko, the deputy legislative head, said Evenkia has plenty of room to develop oil while preserving some of the wildest open spaces on Earth.

There have been suggestions “to preserve this land in its most natural condition, and develop industry only in those areas where oil has been found,” he said.

“I believe our mentality will change so that people will realize the importance of organizing a natural preserve here.”

Evenkia’s future is best served by “a merger between politics and business” that allows the district to help Yukos grow and Yukos to help the district become rich, Odnolko said.

“This kind of participation and cooperation doesn’t hurt anyone,” he said. “It only makes things easier for everybody.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.