Poppy Farmers Have Barren Fields and Empty Purses

- Share via

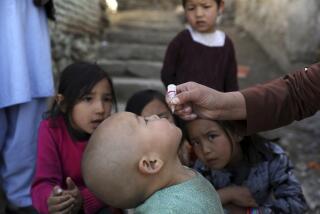

KAPISA PROVINCE, Afghanistan — As Aqa Sherin watched soldiers destroy his $3,000 opium poppy crop in July, he was told he would soon receive humanitarian aid to tide him over until he could reap a legitimate harvest.

Six months later, with winter and hunger biting him, his wife and nine children, Sherin is still empty-handed.

The plight of Sherin and hundreds of farmers like him illustrates a sticking point in the Afghan government’s anti-drug campaign. The lack of compensation for many poppy farmers is creating problems for President Hamid Karzai’s political allies and friction in his relations with donor nations over how the war on drugs should be waged.

The dispute is the residue of a nationwide crop eradication effort that by most accounts was more successful than expected, with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration reporting the destruction of up to 25% of poppies planted last year -- though the harvest was still far larger than in 2001. On Monday, a U.N. agency reported that Afghanistan is still the world’s biggest producer of opium poppies.

Karzai’s national security advisor, Zalmai Rassoul, last month said his government’s position is that donors should make more aid available to farmers like Sherin, if not in the form of direct compensation, then with quick-impact public works projects that would put farmers to work, pump money into rural economies and provide visible signs of progress in the drug fight.

Such projects might give farmers financial alternatives to cultivating poppies, stave off the influence of organized crime and, not least important, maintain Karzai’s credibility with the Afghan people.

“When they destroyed my poppies, they told us they would give us something,” said Sherin, a 35-year-old disabled former guerrilla who fought with the Northern Alliance, which helped bring Karzai to power. “Now our life is zero. The same thing happened with my gun. They came and took it from me, told me I would get $200, and I have nothing.”

International backers of Karzai’s anti-drug effort never promised to pay for an open-ended program of direct compensation to farmers whose poppy crops are destroyed. Though the donors, led by Britain, initially came up with money for such efforts, they now favor a more comprehensive approach to fighting drugs that includes creating reliable police forces and court systems and funding long-term economic and infrastructure development.

Under current circumstances, fresh cash infusions to poppy farmers would be drained away by corruption and inefficiency, said a top Western official who asked not to be identified.

“There is a need to design a larger program, and there is a need for aid workers to be present in these areas to monitor and supervise the progress,” the official said. “But much of the country remains inaccessible because of poor security.”

Long-term strategy aside, the failure of the Karzai government to come through with economic assistance for farmers is jeopardizing future eradication efforts, said Sayed Ahmad Haqbin, governor here in Kapisa province, where 100 farmers share Sherin’s plight.

“It was logical for people to expect humanitarian help, and we did expect it from the international community,” Haqbin said. “But the government is telling us they have nothing. I can’t even pay the drivers we hired to haul the poppies away to be burned.”

Karzai and his international allies are working on a 10-year program that will involve several ministries and hundreds of millions of dollars in aid directed at fighting poppy production, several sources said. The government is hoping for sizable anti-drug funding from the U.S. this year as part of a $3.3-billion Afghan assistance bill approved by Congress in November.

“But President Karzai is impatient that international aid come quicker in the short term,” Rassoul said. “If you don’t act quickly, organized crime sets in, eradication efforts suffer, and you will see a rise in drug addiction in Afghanistan.”

The dispute simmers after a year in which poppy production boomed in Afghanistan, despite the eradication effort’s successes, and is expected to expand again this year. Poppy cultivation in 2002 rose to 180,000 acres before the eradication effort began. According to the United Nations, that was nine times the farmland dedicated to the plants the previous year under the Taliban, which outlawed opium growing in July 2000 and imposed the death penalty for its cultivation.

The U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime reported Monday that opium production here hit 3,770 tons last year, still below the peak of about 5,030 tons in 1999, just before the Taliban edict.

“There is a problem with being able to enforce the rule of law there,” a DEA spokesman said of Afghanistan, adding that about 80% of the heroin produced from raw opium in Afghanistan and its neighbors goes to markets in Western Europe and Russia.

With their traditional agricultural economy based on fruit and nuts left a shambles by drought and more than two decades of war, many Afghan farmers trying to survive tough times see poppy as an easy cash crop. The plants need relatively less water and fertilizer than many other crops. Opium and heroin have long shelf lives.

“Last year was my first time planting poppy,” Sherin said, scooping up a handful of leftover poppy seed on his now-barren two-acre farm. “I was wounded in the leg by the Taliban, and I couldn’t do any other business.”

Karzai is under pressure from Western nations to carry out the anti-drug campaign but lacks the police and military forces in the rural areas to impose his authority. A new national army and police force are in training but at least two years from reaching critical mass, the government acknowledges.

That is why the success that the eradication campaign achieved surprised so many. But implicit in those accomplishments, Afghan government officials say, was the belief that international donors would foot the bill for aid to farmers.

The British put up more than $60 million for such help. However, the money was spent elsewhere in Afghanistan long before it might have reached Sherin and his farm on the Shomali Plain, about 50 miles northeast of the capital, Kabul, and the funding was not renewed.

Sherin and several farmers in the plain have sent petitions to Karzai demanding assistance. Angry farmers also have demonstrated in Helmand and Nangarhar provinces, whose governors in turn have come to Kabul to plead with the central government for financial help.

The Karzai administration is pressing ahead with a comprehensive policy to fight poppy cultivation that will include not just eradication tactics, law enforcement and “alternative livelihood” aid but also rural economic development and infrastructure projects, from road-building to health and education.

But with the government struggling to deal with crises on numerous fronts -- from the return of 2 million refugees, to unbridled warlords and replacement of the nation’s obliterated infrastructure -- the long-term anti-drug effort, which will cost hundreds of millions of dollars, is months from implementation.

At the insistence of the British, overall authority for the counter-narcotics campaign was turned over to the National Security Council, a panel of advisors that Karzai set up in October to exert more control over a government that includes about 30 ministries. Mirwais Yasini was named anti-drug czar.

Although the British have taken the lead among countries helping Afghanistan shape its anti-drug policy, the U.S. has provided nearly $75 million.

That includes an $11.5-million “cash-for-work” project aimed at putting farmers to work eradicating poppies. It also includes $1.7 million for a U.N. effort to build the Afghan government’s drug enforcement program.

An additional $60 million in emergency funds were appropriated by Congress last year for counter-narcotics and law enforcement aid.

Sherin, meanwhile, waits for help.

“Four or five hundred dollars would have been enough for the winter,” he said. “Maybe they will reopen a factory here someday. Until then, there is nothing for me to do except follow my cow around the field.

“I am trying to be patient and not oppose the new government, but we are suffering from poverty and disaster,” he added. “Life is very hard.”

*

Kraul reported from Kapisa province and Efron from Washington. Times staff writer Maggie Farley at the United Nations contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.