Billionaires, Beggars Pray for Luck at Muslim Shrine

- Share via

LAHORE, Pakistan — What do you desire? A bite to eat. A new job. Or perhaps the power to overthrow the government. For dictators and democrats, billionaires and beggars, a Pakistani shrine has for centuries been a magnet for anyone in need of a little help.

There are thousands of shrines of the Sufi creed throughout the Muslim world, but few enjoy the status of Data Darbar, built around the tomb of an 11th-century Afghan scholar famous for his ability to make people’s wishes come true and for his success converting millions to the Muslim faith.

Followers -- including most of Pakistan’s leaders since it gained independence in 1947 -- believe that praying and making donations of money and food to the thousands of beggars at the site in the eastern city of Lahore will bring them good luck.

Former Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was a famous visitor in the 1970s, asking for help in winning elections or in keeping his campaign promises to the poor.

Bhutto’s luck ran out, however. He was ousted in 1977 and hanged by military ruler Zia ul-Haq. Zia also made frequent visits to Data Darbar. He died in a mysterious plane crash in 1988.

More recently, the shrine has been visited by President Pervez Musharraf, a general who seized power in 1999 and exiled the civilian prime minister. Musharraf offered prayers and laid a shawl at Data Darbar before a crucial July 2001 summit with nuclear rival India, and again in April before a controversial referendum that extended his presidency by five years.

Some of Musharraf’s critics in Pakistan’s religious right, who bristle at his embrace of the U.S.-led war on terrorism, scoffed at his visits to Data Darbar, saying they were more about wooing voters than true belief.

“President Gen. Musharraf has only one school of thought, the American school of thought,” said Amir ul-Azeem, spokesman for Jamaat-e-Islami, Pakistan’s oldest and most organized radical Islamic group. “Even his countless visits to the shrines can’t change him.”

Ul-Azeem said his group’s leaders, by contrast, visit shrines to receive “spiritual satisfaction” and get inspiration by following the teachings of great scholars.

The shrine was built to house the remains of Data Ganj Bakhsh, an Islamic scholar who was believed to be a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad and who traveled to Lahore from his native Afghanistan in 1039.

Legend has it that one day, a peasant woman donated a jar of milk to him and returned to her farm to find her cows able to give endless amounts of milk. Data Darbar means “Shrine of the Giver.”

On a recent day, long lines of men waited their turn to kiss the marble mausoleum holding Data Ganj Bakhsh’s remains. Many shook and muttered to themselves as they approached, looking skyward for inspiration.

“I am just a beggar in your house,” said one man, deep in prayer, his hands pressed up against the tomb’s walls. “Please help me as you can do anything.”

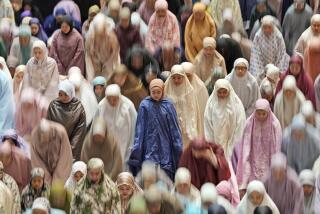

Others lighted oil lanterns and sprayed water scented with rose petals. In the sprawling marble courtyard, thousands sat and prayed, some with their heads buried in copies of the Koran, Islam’s holy book, and other religious texts.

“He is for everyone, poor and rich alike,” said Sheik Basheer Ahmed, 86, a stooped-over perfume salesman who said he has prayed at the shrine four times a day for the past 55 years. “He is a giver and a saint, the king of kings. Everything I have in life I get from here.”

The shrine’s rewards aren’t all otherworldly. Hundreds of people make their living selling trinkets, flower garlands and food outside Data Darbar’s sprawling marble courtyard. Thousands of poor people come night and day to receive rice, milk and other food donated by the wealthy. Orphans and abandoned children swarm around the holy site, begging just enough to stay alive.

Ahmed and other followers of Sufism believe that ordinary people are too sinful to address God directly and must instead make their requests through pure and learned saints, or Sufis. In Pakistan, the belief is most prevalent among the poor, many of whom pin all their hopes on the power of the Sufis.

Indeed, shrines play a vital role in helping feed the poor, both through handouts and the menial jobs that surround the sites. But critics such as Ali Akbar Mansoor, a professor at Lahore’s Punjab University who has written on the role of shrines in Muslim society, say the relief is temporary, and the cure may be worse than the disease.

“Yes, people who are hungry can get food at the shrines, but like beggars. It is not a system. It is not a long-term solution to the problem of poverty,” Mansoor said. “Ultimately, people must realize that the key to success lies within themselves and not in the power of any shrine.”

Lahore has half a dozen well-known shrines, each based on a slightly different philosophy. Many host drumming and dancing rituals that are meant to bring participants closer to God.

At the Baba Shah Jamal shrine, a few miles away from Data Darbar, the dancing runs late into the night, heavy with the smell of hashish.

At Data Darbar, worshippers brushed off the criticism of nonbelievers.

“If you go to a saint and he doesn’t relieve your pains and answer your prayers, what kind of a saint is that?” Ahmed asked, surrounded by men nodding in agreement. “None of us would come here if it didn’t work.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.