Plant DNA in Fabrics May Catch Smugglers

- Share via

For more than a decade, DNA has helped investigators find and convict criminals wanted for murder, robbery or rape.

Now the double helix can help uncover a different sort of crime, albeit a less deadly one: smuggling.

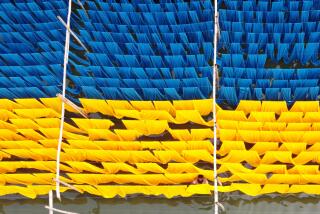

A unique code of plant DNA is being used experimentally in apparel and yarn, allowing U.S. customs inspectors to detect the origin of imported raw materials, the source of the finished garment, and even where the shipment is heading.

Officials can confirm facts in invoices by using a simple, quick test on the textiles. The technology also can be used to authenticate brand labels and to bust counterfeiters, its developers say.

The United States offers duty and tariff breaks to some countries where clothing is manufactured using yarns and textiles produced in this country. Some carriers and brokers falsely claim to meet that criterion to avoid fees.

“The original intent was to be able to ascertain whether or not this product that comes back into the States that says it’s using U.S. yarn and fabric is in fact doing so,” said Jim Leonard, deputy assistant secretary for textiles, apparel and consumer goods industries at the U.S. Commerce Department.

The new technology could have a big impact on operations at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the busiest on the West Coast, which handle about 3 million containers a year and where $4.5 billion in duties and tariffs was collected last year.

For years, the textile industry has been pushing what is now called the U.S. Bureau of Customs and Border Protection to take more aggressive action against smuggling at the ports, said Cass Johnson, senior vice president of the American Textile Manufacturers Institute.

In 2002, customs agents seized $9.3-million worth of apparel being shipped into the country illegally, said Janet Labuda, director of textile enforcement and operations at the customs bureau. But Johnson estimates that that is only a fraction of the goods -- most of which come from China -- that are successfully smuggled into the United States.

“People don’t seem to believe how big the problem is; you can’t wrap your mind around it,” he said.

He cited one case in which 5,000 containers of apparel worth up to $500 million arrived in Los Angeles in February. Because the containers were marked for export, about $60 million in fees that would have been levied over three years were not.

“They ended up in the States,” Labuda said. “But where, we’re not sure. They may be in your closet.”

Another way to avoid fees is to falsely label containers holding apparel with the names of goods that have lower tariffs, such as stating that a load contains lawn furniture when it contains clothing, she said.

Johnson said the odds of getting away with that kind of deception are good, because customs officials examine only 4% of all cargo arriving at U.S. ports.

“This is a huge invitation for lots of nefarious stuff to happen,” said Johnson. “It’s very easy to smuggle goods in. There are people in the Far East who are aware of it; they use it and we lose jobs because of it.”

To help combat the problem, the government began a review of textile-tracking technologies earlier this year. The Oak Ridge National Laboratory selected three possibilities, including the use of plant DNA, a technique developed by Applied DNA Science of Los Angeles.

In the next phase of the project, Oak Ridge will recommend the most affordable technology to the textile and apparel industry and then conduct plant trials and deployment, said Dr. Glen Allgood of Oak Ridge.

Nano-barcodes -- about the diameter of a hydrogen atom -- and ultraviolet fluorescent marks invisible to the naked eye are two other methods being considered, Allgood said.

The use of ultraviolet markings not visible in ordinary light was developed by Oak Ridge, he said. For the nano-barcodes, tiny particles would be structured to form a code, and special optical readers would be used to read them on textiles, Allgood said.

Although these technologies were originally sought to help the government, they can also be used to authenticate designer-brand clothes.

“One of the beautiful things about these technologies is that they have multiple layers. You can design them for all sorts of things,” said Leonard of the Commerce Department. “So it would be there ... for quality control,” and to authenticate brands, he said.

Many designers send materials and patterns overseas, where the finished product can be assembled cheaply. But sometimes the materials are tampered with before they are returned, said Kristin Gabriel, an Applied DNA Sciences spokeswoman.

Larry Lee, chief executive of Applied DNA Sciences, said the idea of embedding DNA in textiles is not new.

“A lot of companies in the ‘90s tried to do this,” he said. “But once they put it in, it only lasted two weeks to three months.”

The problem, he said, was in stabilizing the DNA -- which is sensitive to ultraviolet light -- so that water, heat, sunlight and solvents, among other elements of manufacturing processes, would not make it deteriorate.

Applied DNA’s partner, Biowell Technology Inc. in the Philippines, found a way of stabilizing the DNA for up to 100 years. It can be sprayed onto fabric during various steps of the production process, or a label with DNA in it can be applied.

Inspectors can swab a DNA label that -- when authentic -- turns pink for 10 seconds, then returns to its original blue. Currently in the works are hand-held scanners that will give a more thorough read.

Could the product be cloned?

“It would be virtually impossible for a counterfeiter to replicate or counterfeit the DNA. There are multiple barriers,” Lee said. “They would first have to have a biotech lab and understand the technology of how to decode and stabilize DNA, and then they would have to have the technology of how to detect DNA.”

Despite Lee’s assurances, Allgood says no security technology is foolproof.

“There are a lot of smart people in the world,” Allgood said. Given enough time, he said, someone might be able to break the textile marker technologies.

The key, he said, is to make the prospect of cloning so tough that it would be cost prohibitive.

Applied DNA Sciences’ visions go far beyond the world of fashion. The company is also looking at ways of authenticating pharmaceuticals, artwork, airplane parts, computer software and food.

“If there’s any attempt within the legitimate process to bastardize the product, you can check it and know whether your manufacturer is doing what it’s supposed to do,” said Julia Hunter, a company spokeswoman.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.