Anachronistic Altruist

- Share via

Beijing — He secretly washes other people’s socks, scrubs public toilets and fixes potholes in his spare time. He mails his meager savings to poor peasants, helps strangers carry their luggage home, even slips off his own padded pants to warm a shivering child.

He does this because “life is limited,” he once said. “But to serve the people is limitless.”

He is Lei Feng, a ghost from communist China’s past.

Four decades after Mao Tse-tung made the young soldier a household name, the late Lei Feng’s brand of ultra-altruism is back, dusted off and repackaged to serve a populace in search of a new moral compass.

To celebrate the 40th anniversary this month of his elevation to national icon, official media honored him with the equivalent of MTV specials, running daily documentaries and news reports about his life and interviews with his army buddies. College students took to the streets to give free computer and legal consultations, soldiers fanned out to scrub highway dividers, and little children held study sessions, all in the name of the soldier who died unceremoniously in 1962 at age 22 after being struck by a falling telephone pole.

But today’s China is so removed from even the illusions of a communist utopia that Lei’s selfless deeds appear hopelessly out of date, especially to an Internet-savvy generation increasingly alienated from the idea of worshiping a socialist saint.

“Lei Feng is a pathetic bug,” wrote one Netizen. “When he was alive he made a fool of himself. Now that he’s dead, they still parade him around for public ridicule. He is the saddest and silliest figure in recent Chinese history.”

“You can’t force the Lei Feng spirit on us,” wrote another. “Society must move forward. Our generation should pay more attention to the spirit of Bill Gates.”

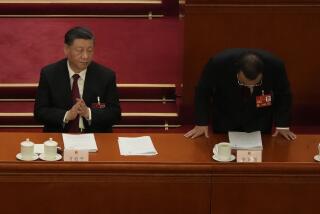

To the geriatric rulers of the most populous nation, however, Lei represents an evergreen model of exemplary citizenship and an all-purpose tonic for society’s changing needs. The government, which underwent a sweeping leadership reshuffle last weekend, faces daunting social problems resulting from two decades of mind-boggling economic reforms.

The resurrection now of Lei is a reminder that however much China changes, some things remain conveniently stuck in the past.

“I’ve watched this thing come back again and again and again,” said Orville Schell, a longtime China watcher and dean at the Graduate School of Journalism at UC Berkeley. “Every time, it gets a little more laughable, because China gets a little further away from this naive socialist model worker, model soldier campaign.

“It suggests the utter bankruptcy of imagination in terms of solutions to very real problems -- in this case, greed, corruption, selfishness, embezzlement of state property and public funds,” he said.

Looking back, it seems that every time the Communist Party needed a simple public relations campaign to paper over serious cracks in the system, it counted on the loyal soldier to do the job.

Right for the Times

In 1963, Mao plucked Lei out of obscurity to help distract the nation in the aftermath of the disastrous Great Leap Forward. The campaign to collectivize farms and industrialize the country at all cost, begun in 1958, had resulted in a famine that killed at least 30 million people.

In the government’s eyes, Lei made an ideal role model because he never questioned authority. A poor orphan from a peasant family, he owed his life to the communist revolution. Among other things, he was indebted to the People’s Liberation Army for bending its enlistment rules; at 5 feet tall, he was too short to qualify.

His goal was to do anything the party said. He famously likened himself to “a tiny screw” in the great socialist machinery. That spirit has since been immortalized in his diary of good deeds, reprinted during various “Learn From Lei Feng” campaigns.

“Today is Chinese New Year’s Day,” read an entry from February 1961. “Everybody else went to see a play. I want to do something good for the people. So after breakfast, I went to shovel manure. I collected about 300 pounds of manure and offered them as a gift to the [local] people’s commune.”

“‘Some people call me a fool,” he wrote in 1960. “I want to be useful to the people, useful to the country. If that makes me a fool, then the revolution needs fools like me. The country’s development needs fools like me.”

Out of Step

When the decade-long Cultural Revolution began in 1966, the good soldier’s total obedience faded to the background. It didn’t match the rebellious, break-everything spirit of the Red Guards.

After the once-purged Deng Xiaoping became “paramount leader” in the late 1970s, Lei resurfaced. The campaign signaled the nation’s nostalgia for a relatively kinder and gentler society, back to the days when Lei inspired young people to help old ladies across the street and moved strangers to return lost wallets to the police.

The lessons of Lei’s total submission to the party were particularly useful following the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, during which hundreds, perhaps thousands, of demonstrators were slain by troops. His familiar face was trotted out again to glorify soldiers who died crushing the protests.

Beginning in the 1990s, however, economic reforms shifted into overdrive and the nation became obsessed with making and spending money. The economy has come to depend on people’s ability to junk the frugality of Lei, who showed his love of country by darning old socks and worn-out bedsheets for himself and comrades.

That makes Lei’s current revival difficult to interpret.

Some see it as part of newly installed President Hu Jintao’s drive to tout the old revolutionary virtues of plain living and hard struggle and set himself apart from corrupt officials in the party.

Others wonder whether another power struggle is on the horizon and whether Hu’s call to old ideals is being used to attack the party’s landmark decision last year to welcome capitalists into its ranks.

More generally, it speaks to Beijing’s worries about social instability, rising unemployment and the growing gap between rich and poor. It also shows the generational divide between the country’s top leaders and a rapidly changing society.

“It’s a reminder this government and Communist Party come from another time and the ideology of the time has not been completely overthrown,” said Schell. “That’s why reform is so difficult. Without getting rid of the past and canceling all of the symbols like Lei Feng, it’s very difficult to move to the future with a new agenda.”

But there are small signs of progress in this latest resurrection. Officials clearly are attempting to give the old hero a more realistic make-over.

For the first time since Lei died, authorities have made public a picture of him wearing a wristwatch while in his army uniform. That hint of materialism would have scandalized old China; now it gives him a touch of humanity.

Authorities also allowed the media to zero in on other aspects of his life previously considered taboo: that he owned a leather jacket, liked keeping his bangs long and enjoyed being photographed.

“The new government realizes that there is a moral vacuum in today’s society and there has been too much attention paid to the pursuit of material wealth,” said Zhao Xiao, an economist at Beijing University. “If learning from Lei Feng could help restore our lost moral boundaries, even the symbolic quest to do good, then he deserves our praise.”

That’s a tall order for a mothballed soldier. In fact, the death of Mao, the general absence of religion and the emergence of a generation of self-centered “little emperors,” born of the country’s one-child policy, have made China more inhospitable than ever to the spirit of Lei Feng.

“You have lots of Mother Teresa figures in the West,” said Zhou. “You also have nonprofit organizations and a tradition for volunteerism. We have very little of that. That’s why Lei Feng stands out.”

The state also doesn’t have the same power it once did to police people’s thoughts. In fact, it appears to have little control over how official propaganda about Lei is digested and lampooned.

Used as Salesman

One barbershop in central China saw Lei as a great advertising ploy. It ran a “Learn From Lei Feng and Do Foolish Things Sale.” It slashed its prices and even hired a Lei look-alike, in uniform and carrying a fake machine gun, to stand guard outside the store.

To draw attention to Lei’s days of service in the northern province of Liaoning, locals have applied to the Guinness Book of Records to recognize him as the most eulogized soldier in the world.

For those who have little to gain from acting out a tired old script, the seasonal return of contrived generosity amounts to little more than sheer nuisance.

One reporter from a central Chinese city wrote of his efforts to learn from Lei. He went to the local train station and tried to help passersby with their bags. Not one person would let go of their possessions; all accused him of either being crazy or trying to steal their belongings.

“Lei Feng was a product of his time,” according to one Internet posting. “He didn’t have to think about losing his job, paying the rent or medical bills. He could afford to be generous. We live in a different world now.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.