Hu’s Delicate Power Trip

- Share via

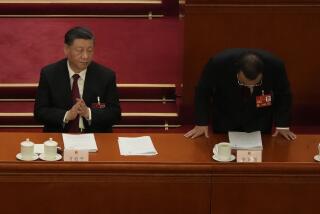

When Hu Jintao took over the top spot in the Chinese Communist Party from Jiang Zemin a year ago, it was unclear how much power he would actually have. In March, he secured a second major post, president of the People’s Republic, once again replacing Jiang. But Jiang has hung on to the chairmanship of the Central Military Commission, retaining his position as the highest-ranking civilian leader of the military.

On the most basic political level, Hu will be successful as a national leader to the extent that he can ease Jiang out of his last official position and move the country in a new direction, one that aims to close a widening income gap among Chinese citizens and embraces a bit more political liberalization.

One of Hu’s greatest successes in shifting the way the government operates came from a rather strange place last year: the SARS epidemic. News of the disease broke just as Hu was taking over the reins of the Communist Party. At the outset, it seemed a setback for the new leader. The government’s first reaction was to deny and lie its way through months of spreading contagion. It appeared that the new leadership team was falling into the all-too-familiar old guard practice of relying on flimsy propaganda to deflect attention from a serious social problem.

In the end, though, the government’s initial failure to respond to the SARS outbreak created a political opportunity that Hu seized. When the full extent of the health crisis could no longer be ignored, Chinese authorities were forced to change their tune. They acknowledged the problem and worked, in a relatively open manner, with the World Health Organization and other medical authorities to find solutions. Hu was able to blame the initial failure on holdovers from the Jiang regime. The minister of health, a Jiang loyalist, was fired. However, Hu too paid a political price: The mayor of Beijing, a Hu ally, was sacked. But when the disease was finally brought under control, Hu got the state media to herald the great victory, a triumph credited to his administration.

On balance, it was a political win for Hu.

If SARS gave Hu an unexpected political boost, the war in Iraq presented a new challenge for his fledgling leadership. The overwhelming American military assault on Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein’s frontline forces demonstrated to the Chinese just how far behind the U.S. they were in terms of military power. Talk of transformation, of paring down the number of military personnel and enhancing technological capabilities, gained new momentum in China, just as had happened after the 1991 Gulf War.

The primary political winner in this discussion was the man at the top of the military hierarchy: Jiang. It was he who announced a new modernization plan for the Chinese military, reminding the world that although Hu may be president, he is not commander in chief.

The unusual cohabitation of Hu and Jiang at the very top of China’s political structure has made for tension on economic and social policy. Over the course of his 14 years in power, Jiang came to emphasize economic growth as the leading national priority. And growth happened to a remarkable degree, topping 10% in some years during the 1990s. But the cost of explosive growth has been rising inequality, as rural incomes have failed to keep up with urban wealth, and increasing numbers of underemployed workers have fallen behind upwardly mobile professionals. Today, the greatest problem facing China is how to control the rising number of protests by poor farmers and demonstrations by out-of-work laborers. With little in the way of a social safety net, the situation could explode into large-scale public disorder.

Since becoming party chief, Hu has articulated a different national vision, one that shifts attention to the have-nots. He has made well-publicized visits to impoverished areas and crafted government pronouncements to aid the disadvantaged. He has invested significant political capital in creating an image of himself as champion of the common man.

It is not at all clear whether he can engineer a major redistribution of wealth. If new regulations limit growth too much, social unrest would be all but certain. For this same reason, Hu cannot give the U.S. what it has asked for: an upward adjustment of the Chinese national currency in relation to the dollar. Too much appreciation of the yuan might undermine the formidable export machine that keeps the Chinese economy afloat. Hu cannot wander too far from Jiang’s high-growth, export-oriented orthodoxy, but he seems determined to shift what resources he can toward lower-income groups.

Whatever his intentions, however, Hu has not yet been able to turn the sprawling bureaucracy in the direction he desires. Some of the problem is institutional inertia: It takes time to move such a vast organization. But politics are also an impediment. Implicit in Hu’s plan is a critique of Jiang’s growth-at-all-costs view and a weakening of Jiang’s immediate political power. Jiang is aware of this and, therefore, before stepping down, he packed key party committees with functionaries loyal to him and his pro-growth ideology. As long as he can hold onto his position as overseer of the military, Jiang can use his influence to keep his cronies in line and limit Hu’s efforts to take the country in a new direction.

The political standoff provides some insight into Hu’s recent call for democratic change in China. In an Oct. 1 speech, he said: “We must enrich the forms of democracy, make democratic procedures complete, expand citizens’ orderly political participation and ensure that the people can exercise democratic elections, democratic decision-making, democratic administration and democratic scrutiny.” This statement must have worried Jiang, who was the chief beneficiary of the violent suppression of the 1989 Chinese democracy movement. And although Americans would certainly warm to Hu’s apparent embrace of democratic values, we should not expect a sweeping transformation of Chinese politics.

In high-level party meetings after his call for democracy, Hu has worked to change parliamentary and decision-making procedures in order to reduce Jiang’s power. Under the banner of instituting “inner-party” democracy, Hu is trying to encourage his supporters to back his leadership more fervently and, when the time is right, to vote to oust Jiang from his last official position.

It is a delicate political maneuver, much of which will play out behind closed doors, but it is a contest that could determine a whole range of economic and social policies in the coming years.

And who knows, if Hu’s efforts at “inner-party” democracy prevail, perhaps political liberalization will expand from the top administrative echelons to the citizenry at large. Thus far, Hu has not shown himself to be a committed democrat, as evidenced by continuing limits on free speech and other civil rights. But if he finds himself more secure in his position, he would at least have the opportunity to respond to China’s modernization with a self-confident step toward genuine democracy.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.