Paradise Regained: Research Uncovers Cities of Amazonia

- Share via

Deep in the Amazon forest of Brazil, archeologists have found a network of 1,000-year-old towns and villages that refutes two long-held notions: that the pre-Columbian tropical rainforest was a pristine environment unaltered by humans and that the rainforest could not support a complex society.

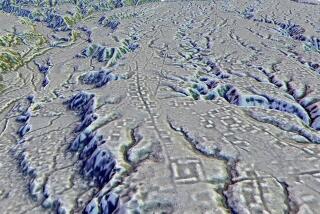

A 15-mile-square region at the headwaters of the Xingu River contains at least 19 villages that are sited at regular intervals and share the same circular design. The villages were connected by a system of broad, parallel highways, researchers report in today’s issue of Science.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Sept. 20, 2003 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Saturday September 20, 2003 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 36 words Type of Material: Correction

Amazon -- An article in Friday’s Section A about an archeological site in the Amazon region incorrectly stated that 16th century Spanish explorers brought new diseases to the area. The diseases were brought by Portuguese explorers.

The Xinguano people who occupied the area not only built the complex towns but dramatically altered the forest to meet their needs, clearing large areas to plant orchards while preserving other areas to provide them with wood, medicine and animals.

Researchers have theorized for 10 to 20 years that such societies were possible in Amazonia, said archeologist James B. Petersen of the University of Vermont, “but this is the first proof.”

The new findings are a crucial part of “a growing body of evidence that Amazonia could support reasonably large villages and complex societies,” said archeologist Robert Carneiro of the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

The region today is composed primarily of small villages with populations of less than 150 people each, and every village is independent of other settlements. Until the current study, most of the Xinguano remaining in the region were not even aware of the accomplishments of their ancestors before the population was decimated by diseases brought by the invading Spanish in the 16th century, said archeologist Michael J. Heckenberger of the University of Florida, who led the research.

Current attitudes about the region were shaped nearly 50 years ago by researchers such as archeologist Betty J. Meggers of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, whose research led her to conclude that the Amazon basin was a “counterfeit paradise.”

Despite the seeming abundance of plants and wildlife in the rainforest, she said, the soil in the region is so poor that it could not support the intensive agriculture necessary for the establishment of large communities.

Little evidence has been collected to refute that idea, Petersen said, largely because the Amazon area -- roughly the size of the United States -- is one of the “last poorly known archeological regions on the face of the Earth.”

Researchers have found bits and pieces of artifacts hinting at the presence of large populations, he said, but no firm proof -- until now.

Heckenberger has been working in the region for a decade and has lived for two years with the tribe that now occupies the area. In fact, his team included two members of the tribe who proved to be adept field researchers.

The 19 villages, which were occupied between roughly AD 800 and 1600, were arranged in two large clusters, each supporting populations of 2,500 to 5,000 people. Residential areas in the villages were dispersed in a large circle around an empty hub, which probably was ceremonial, Heckenberger said.

The individual villages were about 1 1/2 to 2 miles apart, connected by straight roadways that were as much as 150 feet wide, some with high mounds or “curbs” along their edges. The team also found man-made ditches in and around the ancient settlements, bridges, artificial river obstructions and ponds, raised causeways, canals and other structures, many of which are still in use today.

“They are organized in a way that suggests a sophisticated knowledge of mathematics, astronomy and other sciences,” Heckenberger said. “It’s not Earth-shattering compared to what was going on in the rest of the world at the same time, but nobody expected it in the Amazon.”

Heckenberger estimates that more than half of the forest in the region was cut down and replaced with fruit orchards and fields of cassava, an edible root that grows better in the poor soil than most other crops. He speculates that the Xinguano got about 80% of their calories from the cassava, which is still prepared today in much the same fashion as it was in the pre-Columbian era. The remainder of the diet was composed primarily of fruit and fish.

“They had a lot of fish, and they had the means available to harvest lots of fish,” he said. “The way they cooked manioc [cassava] may also retain more nutrients than we thought.”

The Upper Xingu region is so remote that Europeans did not reach the area until the mid-1700s, more than 200 years after the first colonists arrived in Brazil.

By then, most of the villages had been abandoned, their populace devastated by smallpox, measles and influenza brought by the Europeans.