Detainee Pleads Not Guilty as He Challenges His Judges

- Share via

GUANTANAMO BAY, Cuba — Australian David Hicks pleaded not guilty to terrorism-related charges Wednesday, as a second day of military commission hearings brought a second wave of efforts to oust panel members and to throw out the commission system.

As Hicks, 29, dressed in the first suit he had even worn, sat quietly a dozen feet from the family he had not seen in five years, his lawyers challenged the fitness of the presiding officer, Army Col. Peter Brownback, and other panel members. The unusual challenge echoed efforts the day before, by the lawyer for another detainee, to oust the same members.

Hicks’ international defense team -- an American civilian lawyer, an Australian consultant and two Pentagon-appointed military lawyers -- expanded a broad attack, begun Tuesday by the lawyer for detainee Salim Ahmed Salim Hamdan, on the panel’s fitness to serve and on the military commission system. They sought to disqualify the entire panel for lack of legal expertise, noting that only Brownback was a lawyer and that panel members had had trouble defining such basic legal terms as “jurisdiction” and “jurisprudence.”

The legal assault, which grew increasingly heated Wednesday, occurred as representatives of U.S. nongovernmental organizations united in the conclusion that the military commission trials -- the first held since World War II -- were fundamentally unfair, because rules of evidence that allowed hearsay and other rules that barred an appeal to any court outside the Pentagon’s own internal appeals panel.

Anthony Romero, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union, noted that unlike the Yemeni who went before the commission Tuesday, Hicks had four lawyers.

“The best efforts of their counsel are not going to fix a fundamentally flawed process,” Romero said.

“If it can’t work in the case of Mr. Hicks, it raises serious doubts about whether it can work for anybody.”

Lex Lasy of the Law Council of Australia, who joined an Australian government organization to observe the Hicks case, called the military commission’s procedures “unusual and foreign.”

“My main area of surprise is about this combination of judge and jury on the panel,” Lasy said. “How that is going to work out, to me, is a bit of a mystery.”

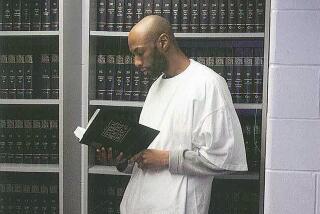

The second day of the little-used brand of military justice began with Hicks, a convert to Islam, walking in leg irons and an ill-fitting dark suit into a room near the courtroom, greeting the father and stepmother he had not seen since disappearing five years ago. He was captured in Afghanistan in late 2001 and taken to Guantanamo in January 2002.

“It was an emotional parting,” the defendant’s father, Terry Hicks, told reporters afterward.

The elder Hicks described his son as having been beaten by American soldiers in Afghanistan, mirroring the tales of three recently released British detainees, and suffering mental abuse here that has left him struggling to cope emotionally.

“He’s been abused in not very pleasant ways,” the elder Hicks, red-eyed and choking back tears, told reporters.

Asked in court how he pleaded to charges of conspiracy, attempted murder and aiding the enemy, Hicks leaned over the defense table and said, “Sir, to all charges not guilty.” His trial was scheduled to start Jan. 10. He could be sentenced to life in prison if convicted of the charges.

A spokesman for the Australian Embassy to the United States said the two nations had agreed that, if Hicks and another Australian held at Guantanamo, Mamdouh Habib, were found guilty, they would serve their time in an Australian prison.

Yet Australia has not asked for Hicks to be sent home, as Britain has done with five of its citizens, on the reasoning that Australia accepts the United States’ description of Hicks as a Taliban fighter but has no law that would allow him to be detained in his home country, spokesman Matt Francis said.

Hicks’ team filed notice of 17 motions to have the charges against their client dropped, in a series of arguments that one defense lawyer, Marine Maj. Michael Mori, said “attack the whole structure of the commission.”

They argued, among other things, that the panel was not authorized under the Constitution, that the charges against Hicks were not violations of the laws of war and that because the commissions tried only foreigners, they violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution.

Hicks’ lawyers also contend that there is a conflict of interest involving Brownback and the head of the Office of Military Commissions, retired Army Maj. Gen. John D. Altenburg, who appointed the members of the panel. Brownback acknowledged under aggressive questioning that Altenburg was a close friend.

Joshua Dratel, a New York criminal lawyer on Hicks’ team, also alleged a conflict because Brownback’s legal assistant works for the Department of Homeland Security -- a situation Dratel said was akin to hiring a prosecutor as a court clerk. He and Mori also sought to oust Brownback as presiding officer by arguing that the judge’s instructions on matters of law to the other commissioners, none of whom had legal training, would likely result in “unlawful command influence.”

As Hamdan’s attorney did on Tuesday, Hicks’ lawyers challenged the qualifications of other commission members, noting that at least two had participated in the war in Afghanistan.

One was an intelligence officer near the site where Hicks was captured, and another was responsible for moving detainees from Afghanistan to Guantanamo and acknowledged recognizing Hicks’ name.

Two more commission members were challenged on other grounds. One had once commanded a Marine reservist firefighter killed in the attack on the World Trade Center and had attended his funeral and visited ground zero. The other could not explain the Geneva Convention -- the guiding principles of international law during wartime -- and admitted that the attacks angered him.

Defense lawyers expressed astonishment that the military could not find members of the panel -- who serve as judge and jury -- with fewer apparent conflicts of interest.

“It’s inconceivable to me that the United States military cannot find a panel of five that does not have two people who are so intimately involved” in the war in Afghanistan, Dratel said.

A military spokesman noted that combat experience or command experience were criteria for panel members, selected out of a pool of 100, and that as many as 40% of U.S. military personnel have participated in some way in the Bush administration’s war on terror.

Dratel sought to invalidate the entire panel, arguing that the five nonlawyers lacked the necessary legal training and that Brownback was not a current member of the bar in his home state of Virginia, and therefore would not be eligible even as a lawyer in the case.

“I think that several challenges could -- and I think should -- be upheld,” said Neal Sonnett, an observer here for the American Bar Assn.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.