New Malaria Vaccine May Be Lifesaver for Africa

- Share via

After more than two decades of research, scientists said Thursday that they had found the first effective vaccine against malaria. Trials in Africa showed that the vaccine blocked almost half of new infections in young children and reduced serious disease by nearly 60%.

Experts termed the results a major breakthrough in efforts to tame a disease that afflicts 400 million people each year, killing 1 million to 3 million -- most of them children in Africa. Malaria is the leading killer of children under age 5 and ranks with AIDS and tuberculosis on the list of the world’s most lethal diseases.

Researchers are not sure how long the vaccine’s protection will persist, but even a partially effective vaccine would have great value in fighting a disease that is spreading and becoming increasingly resistant to the drugs most commonly used to treat it.

More trials are needed to confirm the vaccine’s efficacy, particularly in the youngest children, who are most likely to die from infections. But it could be available for widespread use by 2010, experts said.

By that time, the World Health Organization predicts, half the world’s population will be living in areas of high exposure to the disease, compared with 41% now.

Other potential malaria vaccines have been tested, “but we have never seen results like this before,” said Dr. Pedro Alonso of the University of Barcelona, who headed the trial reported in this week’s edition of the journal Lancet. The vaccine could make a major contribution to “breaking the cycle of disease and poverty that so badly affects sub-Saharan African countries,” Alonso said.

Producing a malaria vaccine is considered the most urgent goal in controlling the disease, because it offers the safest, least expensive method. Antimalarial drugs such as Larium, known generically as mefloquine, can be used to prevent infection by killing the malaria parasite, but they are much more expensive, require regular use and can have many undesirable side effects.

Developing a malaria vaccine has been difficult because the disease is produced by a parasite with a complicated life cycle. Science has yet to come up with an effective vaccine against a parasite, said Melinda Moree, director of the Malaria Vaccine Initiative.

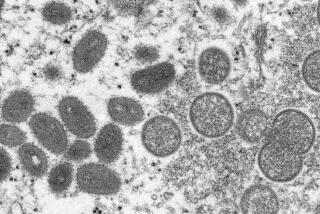

Malaria is caused by four closely related parasite strains, the most common and deadly of which is Plasmodium falciparum. The strains thrive in Anopheles mosquitoes.

The life cycle begins when infected mosquitoes bite humans, injecting them with the form of the parasite called sporozoites. These invade the liver and begin reproducing in a new form called merozoites.

Some merozoites can remain dormant in the liver for years, but most escape into the bloodstream and infect red blood cells, where they continue to replicate. Eventually, the blood cells burst, releasing more of the parasite into the bloodstream. That is what causes most of the symptoms associated with malaria.

The parasites are then ingested by mosquitoes when they bite an infected human. They reproduce in the mosquito’s gut and start the cycle all over again when the mosquito bites an uninfected person. It has proved exceptionally difficult to find a vaccine that can disrupt this complicated history.

The new vaccine, called RTS,S/AS02A, was developed by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. It uses two genetically engineered proteins from the surface of the P. falciparum sporozoites. They are fused to a large protein that is already used in the hepatitis B vaccine. The finished vaccine also contains a combination of nonbiological materials that stimulate the immune system to react more strongly to the proteins.

The trial involved more than 2,000 healthy children ages 1 to 4 living in Manhica in rural southern Mozambique. Half of the children were administered three doses of the vaccine last summer and half received conventional childhood vaccines.

Over the first six months of the trial, those receiving the new vaccine had about 30% fewer episodes of malaria and 58% fewer episodes of severe malaria.

“All malaria deaths start with severe malaria,” Alonso said, so in the long run, the vaccine should produce a significant reduction in deaths.

“That’s pretty impressive,” said Lee Hall, director of the Malaria Vaccine Development Section of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. “The other thing that is interesting, as opposed to earlier studies, is that the efficacy seemed to be sustained over time.”

In the youngest children in the group, Alonso said, there was a 78% reduction in severe illness.

He said that even in those people who contracted malaria, the vaccine appeared to help by impeding the spread of merozoites when blood cells burst.

The next step will be to test the vaccine in even younger children. They are the ultimate target of the vaccine because researchers hope to protect children before they are ever exposed to the parasite. That will require an additional clinical trial, which could take two to three years, with perhaps another two years to move the vaccine through regulatory agencies.

Jean Stephenne, president of GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, also noted in a telephone conference Thursday that it commonly takes five to six years to build a new plant to manufacture a vaccine. If the vaccine is to be available by 2010, he said construction would have to begin no later than the end of 2005.

Although Stephenne said the vaccine could theoretically cost $10 to $20 per dose, a company spokesman later noted: “We cannot yet put a price on this vaccine. It’s not an inexpensive vaccine to manufacture. We expect the price will be reasonable and accessible to those who need it most.”

That price “would obviously put a pretty tremendous burden on those countries if they are expected to pay for it themselves,” said the NIH’s Hall.

Many of the most afflicted countries spend little on healthcare. But Hall speculated that international organizations would underwrite much of the cost of a malaria vaccine.

He said the study found a 30% reduction in hospital admissions among those vaccinated. In Africa, about half of all hospital admissions are due to malaria, so a 30% reduction “could have a pretty dramatic effect,” freeing up money that could pay for further immunizations, Hall said.

The trial was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline and the Malaria Vaccine Initiative, which receives most of its funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.