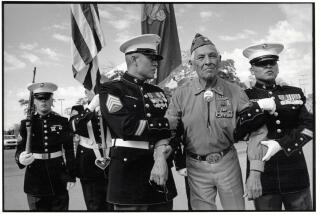

Ex-Marine Seeks Place in Iwo Jima History

- Share via

SOUTH LAKE TAHOE, Calif. — The old man gazes at the photo of the flag flying over Iwo Jima and sees himself 60 years younger, a Marine in uniform with a radio on his back and his head tilted up at the Stars and Stripes.

It’s not the photo known the world over of six men struggling to raise Old Glory. No, this is a black-and-white of the smaller American flag first raised by Marines atop Mt. Suribachi earlier the same day. But because of the iconic later picture, this event is largely lost to history.

And as another anniversary of the flag-raising arrives Wednesday, Raymond Jacobs, 79, says he has been similarly overlooked all this time.

The young radioman in the photo is himself, Jacobs insists. Armed with pictures, news clippings, correspondence and his own account of the siege on the extinct volcano, the white-haired former Marine has been rounding up veterans, members of Congress and authors as allies in his fight for recognition.

“When the folks in Washington, D.C., kept saying, ‘No, no, no,’ I got a little bit pushed so I said, ‘I’m going to prove it to them,’ ” he said. “I understand their skepticism because there have been any number of people who’ve claimed to have been part of this group and they weren’t; they were just telling sea stories.”

*

Jacobs’ story begins Feb. 19, 1945, when he and thousands of Marines were pinned down on the black sand beach as bullets, mortars and artillery rained down from an invisible enemy burrowed in the island. Iwo Jima would be the deadliest battle in Marine Corps history, killing nearly 7,000 Americans.

On the morning of Feb. 23, after a four-man reconnaissance patrol returned from the 550-foot summit of Suribachi, Jacobs says he was ordered to fill in for Easy Company’s radioman on a combat patrol up the mountain. With a 40-pound radio strapped to his back and carrying an M-1 rifle, Jacobs says, he made a nerve-racking scramble up the rugged peak with 40 strangers.

“The amount of fire that they poured down on us in previous days was so incredible that you were twitchy,” he said. “All the time you’re moving, you’re looking around waiting for the first round to hit.”

After making it to the summit without resistance, the men tied a small flag to a length of pipe found in the debris and hoisted it. When it was aloft, a spontaneous roar rose from the shore.

“All of a sudden, you could hear voices down below screaming and yelling and cheering,” Jacobs said. “It was an incredible feeling, a very emotional feeling. The boats who were beached and the big ships at sea started blowing whistles and horns and all the rest of it.”

Lou Lowery, a photographer for Leatherneck magazine, captured the moment from several vantage points. But those photos were not published for two years. That piece of history was shelved when a second patrol planted a replacement flag.

The reason for the swap is not clear. Some suggest that the first flag was taken as a souvenir; others said it was too small.

For whatever reason, a larger flag was run up the hill, and Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal forever defined the moment as five Marines and a Navy corpsman pushed the second flagpole skyward.

Jacobs says he was off the mountain when the second flag went up but spoke with reporters after the first flag-raising. The Feb. 24 front page of the now-defunct Los Angeles Herald-Express says: “Pfc. Raymond E. Jacobs of the Twenty-eighth Marines was revealed in an Associated Press dispatch today as being a member of the patrol of 14 leathernecks who proudly raised the flag on rugged Mt. Suribachi, on the southern tip of Iwo Jima yesterday.” The Los Angeles Times incorrectly put Jacobs’ name in the caption of the Rosenthal photo on its front page the following day.

Jacobs remained in the battle for another two weeks until he was hit with shrapnel from a Japanese mortar and evacuated with wounds that earned him a Purple Heart.

*

Jacobs became aware of the Rosenthal photo only after returning home -- and was puzzled at first because it didn’t depict what he witnessed. It was not until 1947 that Lowery’s picture of the first flag-raising was published in Leatherneck. In response to an inquiry from Jacobs, Lowery wrote that his story had been kept secret because Rosenthal’s shot provided good publicity for the Marines.

Over the years, many others claimed that they were there.

But Jacobs says he was not a glory seeker. “The flag-raising and the patrol became just another event,” he said. “We didn’t see it as a defining moment in our lives. It was just something we had done, and we were happy about it.”

Retired Col. Dave Severance, commander of the company that raised the initial flag, says he’s documented about 50 phony claims by men who said they were there. He says he doesn’t buy Jacobs’ story. Tactically, he doesn’t think that Jacobs’ commander would have released his radioman for the mission.

“We thought we were going to storm that mountain,” Severance said. “If my radioman had left me, he’d still be in jail.”

It was specifically because Severance kept the Easy Company radioman at the command post that a replacement was sent. Severance acknowledges that someone went up Suribachi with a radio, but he disputes that it was Jacobs.

Retired Col. Walt Ford, editor of Leatherneck, says Jacobs was a hero for being on Iwo Jima, but he adds that some people have wondered why he waited so long to raise his voice and why he didn’t attend Iwo Jima reunions when more living veterans could have verified his account.

Ford says the sole recognized survivor of either flag-raising, Charles Lindberg, said he didn’t remember Jacobs. Attempts to reach Lindberg were unsuccessful. But Jacobs and Lindberg both spoke at an event three years ago in Long Prairie, Minn., dedicating a memorial to the first flag-raising. It names both of them. Jacobs also points to the 1947 letter from Lowery as marking his earliest effort for recognition.

Jacobs’ daughter, Nancy, took up her father’s cause 20 years ago. She has made several inquiries over the years but has always been met with polite rejection. Members of Congress who have written on his behalf have been told that while as many as 10 Marines are pictured near the flagpole, only six have been identified as flag raisers. Jacobs says only that he was at the raising.

After retiring in 1992 from KTVU-TV in Oakland, where he worked 34 years as a reporter, anchor and news director, Jacobs began more thorough research. His effort took a leap forward when Leatherneck ran more of Lowery’s photos a few years ago, revealing the shadowy face of the radioman who was out of view in the original photo. Jacobs said he recognized himself immediately.

Forensic photographic expert James Ebert compared pictures of Jacobs with the Lowery photos and found his claim convincing.

Others have recently lent their support.

Parker Albee Jr., a University of Southern Maine history professor and coauthor of “Shadow of Suribachi: Raising the Flags on Iwo Jima,” plans to identify Jacobs as the radioman in an upcoming paperback edition.

James Bradley, son of John Bradley, the corpsman celebrated for raising the second flag, says he can’t prove that Jacobs was the man in the Lowery photos, but he thinks that he was there. Bradley, author of the best-selling “Flags of Our Fathers,” put a link to the Jacobs controversy on his website.

The Marines officially say the radioman near the flagpole remains unidentified. Chuck Melson, chief historian for the Marine Corps Historical Center in Washington, says he believes Jacobs but is remaining neutral.

“His story rings true with us,” he said, “but we’re not going to bless it because we can’t.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.