Callaway Said to Be Target of Takeover Drive

- Share via

Callaway Golf Co. is quietly weighing an all-cash, $1.2-billion takeover bid that would take the nation’s largest manufacturer of golf clubs private, according to sources close to the situation.

The unsolicited takeover offer from buyout firm Thomas H. Lee Partners and insurance mogul William Foley II was submitted to Callaway’s board May 20, sources say. It comes amid an industrywide slump in golf equipment sales and turmoil at Callaway.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. June 24, 2005 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Friday June 24, 2005 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 59 words Type of Material: Correction

Callaway Golf -- An article in Thursday’s Business section about Callaway Golf Co.’s weighing a takeover bid said that Carl Karcher, founder of CKE Restaurants Inc., which owns Carl’s Jr., was dead. He is still alive. The article should have referred to the 1992 death of Karcher’s younger brother, Donald Karcher, who was president of Carl Karcher Enterprises Inc.

The Carlsbad, Calif.-based company, best known for its Big Bertha drivers, has struggled to fill a leadership void since charismatic founder Ely Callaway died in 2001.

Sources say the buyout offer has prompted a pitched battle within the money-losing company between top management and a faction of the seven-member board of directors.

During a meeting Monday of a board committee formed to review the offer, Callaway’s top executive team unanimously endorsed the bid, according to people with knowledge of the discussion. Leading that effort was Callaway Chairman William Baker, 71, a board member since 1994 who has been serving as chief executive since a management shake-up in August.

The board, however, is said to be divided over the offer, with some campaigning to oust Baker as CEO in favor of Anthony Thornley.

Sources say Thornley, who joined the board last year, is angling to get Baker’s job after being passed over in March to run Qualcomm Inc., the San Diego-based wireless equipment company from which he is due to step down as president on July 1.

Shortly after receiving the takeover offer, Callaway’s board asked New York investment bank Lazard Ltd. to explore options and to assess Callaway’s value, people close to the situation said.

A spokesman for the company declined to comment.

Phone calls to Baker, Thornley and Ronald Beard, Callaway’s lead independent director, were not returned Wednesday. Foley and representatives from Thomas Lee also did not respond to requests for comment.

Although the company has not disclosed the offer to shareholders, there were indications that Wall Street had gotten wind of the bid. After hitting a 2005 low in April of $10.78 a share, Callaway’s stock has been drifting upward, closing Wednesday at $13.58, up 18 cents. Analysts said that rally could not be attributed to any changes in the company’s performance or outlook.

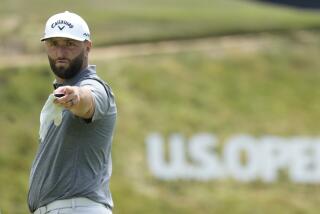

“Even the ratings for the U.S. Open were lackluster,” said Dennis McAlpine of McAlpine Associates, referring to the number of TV viewers who watched the Open, won Sunday by Michael Campbell, using Callaway clubs.

The stock price is still below the value of the takeover offer, which sources say is $16 a share. That represented a 35% premium above the closing price of the shares the day before the bid was said to have been submitted.

On Wednesday, the board had yet to respond to the offer, the sources said.

With $14 billion in funds to invest, Boston-based Thomas H. Lee Partners is among the nation’s largest private equity firms and has taken part in takeovers of such companies as Houghton Mifflin, Nortek Holdings and Warner Music Co. Among its most storied investments was its $135-million purchase in 1992 of Snapple, which it sold two years later for $1.7 billion.

Foley, the insurance mogul, is a veteran deal maker. As chief executive of Fidelity National Financial Inc., he built the company through acquisitions into a leader in title and real estate services. An accomplished golfer, Foley also is chairman of CKE Restaurants, which owns Carl’s Jr., Hardee’s and other food chains.

Foley took control of the restaurant chain in 1994, two years after the death of the company’s founder, Carl Karcher. Through a succession of acquisitions, he pushed the stock to a peak of $40 in 1998, up from $4 a share. By 2000, however, shares had plummeted to $6. Foley soon stepped down as CEO to devote more time to Fidelity.

Foley and Thomas Lee would take Callaway private, cut costs and try to revitalize its brands, sources say. Top Callaway executives back the idea because they believe that product quality and innovation have suffered because of the quarter-to-quarter growth demanded by Wall Street, insiders say. In their view, removing such pressures would revive the spirit of innovation that distinguished the company under its late founder.

Callaway had already retired from a career as a textile executive when, in the early 1970s, he put Temecula on the wine map, founding the region’s first serious winery. He sold Callaway Vineyard and Winery at the end of the decade and ventured into golf manufacturing in the mid-1980s.

By the early 1990s, Callaway Golf had made a name for itself by developing a stainless steel driver dubbed Big Bertha that featured a larger, more forgiving head than other clubs on the market. The company sold stock to the public beginning in 1992 under the symbol ELY, a nod to Callaway’s first name. By 1993, Annika Sorenstam had joined Callaway as a so-called staff golf professional, and three years later, the company had become the world’s largest club manufacturer. Today, Arnold Palmer and Phil Mickelson are also part of the Callaway team.

But the company’s profits have been squeezed by lower-priced models from such rivals as TaylorMade. Sales of Callaway’s clubs have declined 11% since 2002.

Callaway, thanks to the 2003 acquisition of prominent ball manufacturer Top-Flite Golf Co., derived nearly as much revenue last year from balls as from drivers and woods, the products for which it is best known. Golf balls have driven up Callaway’s overall sales since 2002 by 18%, to $934.6 million last year, when the company lost $10 million.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.