WRITTEN IN PAIN

- Share via

Gary Webb planned his death with polite precision.

He typed out four lengthy suicide notes and put them in the mail to family members. He placed his prearranged cremation certificate and Social Security card on the kitchen counter of his suburban Sacramento home. He put the keys to his cars and motorcycles in an envelope addressed to his oldest son.

All his belongings -- among them numerous awards from his years as an investigative reporter -- were packed and neatly stacked in boxes in a corner of his living room. He left a note on the door. “Please do not enter. Call 911 for assistance. Thank you.”

Then, sometime during the evening of Dec. 9, Webb, age 49, went into his bedroom. He put his driver’s license on the bed next to him and placed an old .38-caliber revolver near his right ear.

When he pulled the trigger, the bullet sliced down through his face, exiting at his left cheek, a non-fatal wound. He pulled the trigger again. The second shot, coroner’s investigators believe, nicked an artery.

His body was found the following day.

For weeks after, Internet bloggers buzzed with the news of Webb’s death. Perhaps Webb -- a controversial figure in American journalism -- was murdered. Some saw reason to suspect a plot by the U.S. government; the former San Jose Mercury News reporter gained folk hero status among left-wing conspiracy theorists for writing scathingly about the CIA nine years ago.

Suddenly, the journalist known for unearthing incredible stories had become one.

Two Hollywood agents called Webb’s family to ask about the movie rights. A television station in France sent a crew to file a report. Esquire magazine ran a tribute article.

Inundated with inquiries, Sacramento County coroner’s deputies spent weeks investigating Webb’s death and concluded that his wounds were self-inflicted. (They plan to release their final autopsy results later this month.)

Webb’s suicide has left friends and loved ones trying to sort through tangled feelings about a man who was known not so much for the triumphs of a high-impact journalism career as for what he is accused of getting wrong.

In 1996, Webb produced a series of stories for the San Jose Mercury News that suggested the CIA was involved in the nation’s crack cocaine epidemic in the 1980s as a means of helping Nicaraguan drug dealers funnel money to the Contras. His premise that the government knew about and even encouraged the drug sales -- with South Los Angeles as ground zero -- sparked outrage, especially among members of the African American community.

Government agencies and the media, most notably the Los Angeles Times, launched their own investigations into Webb’s report. Resoundingly -- and some believed venomously -- they dismissed Webb’s thesis. Later, his bosses at the Mercury News all but disavowed the piece, with a front-page editor’s note stating that the series had largely overstated its provocative findings. Eventually, Webb was forced to resign.

As the CIA story began to unravel, so did Webb’s life, sending him down a self-destructive path. While many of his supporters believe that the mainstream media’s condemnation was largely to blame for the journalist’s demise, those closest to him say Webb’s downward spiral is far more complicated.

For more than a decade, the journalist struggled with clinical depression, sometimes so profound that he sought solace in reckless and dangerous behavior. He crashed cars and motorcycles, he had illicit affairs and he took journalistic risks -- beyond what his research could support -- in his stories. (He was sued for libel four times, two of the suits resulting in settlements.)

On the surface, Webb seemed confident and determined. Admired and even idolized by some of his colleagues who later abandoned him, he could dig up any public document, a talent that helped him win more than 30 journalism awards and earned him a national reputation as a dogged investigative reporter.

However, his cocky street-smart style concealed a core sadness that few ever saw.

“By the end of his life he was just in a lot of pain,” said Webb’s ex-wife, Susan Bell. “He was sleeping more, he hated to get up in the morning, he started having a lot of motorcycle accidents.

“I kept saying, ‘Gary has a death wish.’ ”

Isolated yet scared of being alone, Webb tried a cocktail of antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs, prescribed by a doctor. He took Prozac for a while. He mixed Lexapro with Klonopin. He gave up the medications altogether last spring, after complaining to his close friends that they made him feel worse.

With his ego dependent on his job, Webb needed a good story to lift his mood. But after the CIA scandal, no major newspaper would hire him.

He learned a hard lesson: There is no regulatory agency overseeing American journalism, no hearing committee or moderator to sort out disputes. Historically, and without any formal coordination, the profession polices itself, largely because a reporter’s reputation rests on his credibility. Discredited, Webb was ostracized and there was no court of appeal.

Alone, in debt and on the verge of losing his house, Webb told family members in his suicide notes that he was done.

“He told us if he couldn’t write, then what was the sense of going on,” Bell said. “He had just given up.”

Childhood ambition

Since he was in grade school in North Carolina, Gary Webb wanted to be a newspaper reporter. The son of a career Marine sergeant who constantly moved his family, Webb became an avid reader with an interest in government. Coming of age during Vietnam, he believed reporters were duty-bound to act as watchdogs.

In high school in Indianapolis, he joined the newspaper. It wasn’t long before he caused a stir. He wrote an editorial criticizing the drill team for dressing up in military uniforms and twirling rifles and battle flags at halftime during the football games to show their support for the troops in Vietnam.

“I thought it was one of the silliest things I’d ever seen,” Webb later told an audience during a speech in Eugene, Ore., in 1999. The next day at school, the newspaper advisor told Webb to apologize for what he wrote. He refused. Fifteen members of the drill team showed up at the newspaper office.

“They all went around one by one telling me what a scumbag I was, what a terrible guy I was, and how I’d ruined their dates, ruined their complexions, and all sorts of things,” he told the audience, eliciting laughter. “And at that moment I decided, ‘Man, this is what I want to do for a living.’ ”

After finishing high school, he went to Indiana University on a journalism scholarship. He was there about a year before he transferred to Northern Kentucky University, joining the staff of the college paper.

Webb looked like the ultimate 1970s dude, his sandy blond hair cut and feathered into a shag, a style he wore long after it was outdated. He loved horror movies, motorcycles, hockey -- anything for a thrill.

Cigarette dangling from his mouth, Webb could rebuild a car engine, put down a hardwood floor and argue politics with equal passion. Once, wielding a.22-caliber rifle, he chased down a man who tried to break into his Triumph sports car outside his house in Covington, Ky. He fired off a shot, grazing the man’s buttocks as he tried to escape.

His reporting style was equally brazen. Strong-willed and stubborn, Webb relished the idea of being an investigative reporter, one of the fighter pilots of the journalism world. The “I teams” are among the last bastions of male dominance in American newspapers, and Webb enjoyed his place in the elite fraternity of characters known for their macho swagger.

Working as an investigative reporter at small and medium-sized papers, Webb could be the star -- and the editor’s nightmare.

“He wasn’t exactly the kind of person who was crippled with a whole lot of self-doubt,” said Tom Loftus, a friend and former colleague from the Kentucky Post. “I don’t think I would want to engage in a debate over the veracity and solidness of a story with Gary Webb unless you had done your homework.”

If allowed, Webb would infuse his stories with over-the-top language, such as referring to the Contras as “the CIA’s army” in his controversial Mercury News series. Cutting the rhetoric meant a fight.

“All his research was meticulous, but when it came to writing he pushed the envelope,” said Mary Ann Sharkey, who edited Webb early in his career. “I would always find myself deleting adjectives and adverbs. We had quite a few jousts.”

Occasionally, however, Webb offered a glimpse of his softer side: He kept a box of mementos -- his baby shoes, sand from Hawaii, homemade Christmas ornaments. And he married his high school sweetheart.

“His mom used to tell me that I was the only one who could put up with him,” said Bell. “But he had a great sense of humor. He was intelligent and intriguing. He knew a lot about everything.

“He was just interesting.”

Getting his start

Webb was well on his way to getting a degree in journalism when crisis struck. His parents divorced and his mother needed money. With his college newspaper clips in hand, he walked into the editor’s office at the Kentucky Post and asked for a job. The editor, a cantankerous man who liked to call his staff late at night to tell them their stories were awful, took a chance and hired him.

One of his duties included stopping by the police stations and the courthouses to pick up reports and check filings. His curiosity was piqued one day by a police report he discovered. On the surface it seemed like just another homicide: The owner of an adult video store was found dead. Webb dug for months and was able to write an investigative piece that linked the man’s death to organized crime in Kentucky’s coal industry.

Hooked, Webb decided to focus his career on uncovering the misdeeds of the powerful. He went to work for the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s capital bureau in Columbus.

“I well remember coming into the bureau in the mid-morning and stopping by Gary’s office to find him there,” said Sharkey, former statehouse bureau chief for the Plain Dealer. “He had been there all night poring over some arcane records, whether telephone printouts or state leases or whatever document might be the smoking one.”

With the high-profile stories came problems. Webb was sued four times for libel during his stints in Kentucky and Ohio. The first suit, against the Kentucky Post, was dismissed, as was a subsequent suit against the Plain Dealer.

The Ohio paper later settled two additional lawsuits, for undisclosed sums.

One of the suits was filed by a former chief justice of the Ohio Supreme Court, who claimed that Webb’s story -- “Mob-Linked Groups Donate to Chief Justice” -- cost him his reelection. Another case involved two Cleveland Grand Prix promoters, who sued the paper after Webb wrote a story claiming that the promoters took auto-race money that should have gone to charity and to the city. A jury sided with the promoters, awarding them $13.6 million. The paper appealed the decision and eventually settled out of court.

Webb maintained that the stories were backed up by public documents. He was hurt and angry that the paper decided to settle, Sharkey said.

She said he soon came to see legal problems as part of the job. Certainly, the libel allegations did not impede his career. Reporters from all over the country started to call Webb for tips on how to dig up documents and investigate public officials. He was happy to help.

“He was very generous with people, especially young reporters,” Sharkey said.

In 1988, the editors at the Mercury News phoned. The paper wanted to establish a stronger investigative presence. Webb seemed like the perfect fit.

Webb was interested in working for the Mercury News, but he had some conditions. He and his wife did not want to live in San Jose because they thought it was too expensive. He asked if he could work in the paper’s Sacramento bureau instead, and the editors agreed.

“From his clips, he looked like he had tremendous potential,” said Scott Herhold, one of the editors who interviewed Webb. “When he was passionate about a story, he was willing to do the things that we go into journalism for -- to look power in the face and question it.”

On Pulitzer-winning team

Webb’s early years at the paper included an impressive run of stories, though not without controversy. He was part of a large group of reporters and editors that won the Pulitzer in 1990 for spot-news coverage of the Loma Prieta earthquake. He irked his colleagues when he started referring to himself as a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, leading some people to believe that the award went solely to him.

“For Gary to do that smacked of self-aggrandizement,” Herhold said.

He also caused a stir when he wrote a series of stories that blamed Tandem Computers Inc. for failures in a program to modernize a computer system at the California Department of Motor Vehicles. After Tandem complained, the paper assigned a second reporter to look into the matter. The reporter concluded, in a memo to senior editors, that Webb’s series was “in all its major elements, incorrect.”

The paper ran two corrections, and Tandem -- which later was cleared by a state audit -- bought a full-page advertisement attacking the stories and Webb.

But there were other stories that Webb nailed. For example, he wrote a series of stories about police in California taking people’s property under the guise of cracking down on drug traffickers. The state Legislature ended up abolishing the program.

“In his prime, he was the most fearless reporter I’d ever met,” remembers Los Angeles Times reporter Ralph Frammolino, who became friends with Webb while working in Sacramento.

With a nice house, young children -- two sons and a daughter -- and an attractive wife, Webb seemed to have everything going for him. Privately, Webb was struggling. In 1991, a doctor confirmed what he and his wife already suspected: He was clinically depressed.

Bell said she worried about her husband but knew that when he found a good story he would perk up. High-stakes journalism was Webb’s most effective antidepressant.

“Hot stories always pulled him out of it,” Bell said. “When he was writing and into a good story, that was always his best time.”

Then in July 1995 came the tip that led Webb to the biggest story of his career.

A fateful tip

It started with a phone message, written on a palm-sized piece of pink paper and placed on the edge of Webb’s desk. A woman Webb had never heard of wanted to talk to him. She left her name and number, but no other information. Intrigued, Webb phoned back.

The woman was the girlfriend of an accused cocaine dealer. She said one of the government witnesses testifying against her boyfriend used to work for the CIA selling drugs, “tons of it.”

Webb was skeptical at first. “In 17 years of investigative reporting, I had ended up doubting the credibility of every person who ever called me with a tip about the CIA,” he would later write in a lengthy account of the conversation in his 1998 book, “Dark Alliance.”

He quizzed her: “You say you can document this?” She responded: “Absolutely.”

In the weeks and months that followed, Webb spent hundreds of hours combing through documents, interviewing dozens of sources and making trips to Central America.

In August 1996, Webb alleged in a 20,000-word Mercury News series that a Contra-connected drug gang helped fuel America’s crack cocaine epidemic in the 1980s by bringing in large supplies of Colombian cocaine and selling it to black street gangs in Los Angeles, with the knowledge and protection of the CIA.

Webb’s allegation that the CIA-supported Contra army cooperated with drug traffickers was already well known. A congressional subcommittee headed by Sen. John F. Kerry (D-Mass.) issued a 437-page report in 1989, concluding that the Reagan administration had “delayed, halted or interfered” with anti-drug investigations when they conflicted with its effort to help the Contras.

But Webb’s series included three new, and explosive, charges: that a CIA-related drug ring sent “millions” of dollars to the Contras; that it launched an epidemic in the 1980s of cocaine use in South Los Angeles and America’s other inner cities; and that the CIA either approved the scheme or deliberately turned a blind eye.

Crack cocaine -- a cheap but highly addictive street drug -- wreaked havoc in poor neighborhoods throughout the United States. African Americans were hit especially hard. The reaction to Webb’s series was immediate and emotionally charged.

The CIA assigned a special investigator to probe the matter. Congress called for hearings. The Los Angeles Times, Washington Post and New York Times launched their own investigations. One by one, they picked apart Webb and his series.

“The available evidence, based on an extensive review of court documents and more than 100 interviews in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Washington and Managua, fails to support” Webb’s allegations, was the conclusion of the Los Angeles Times’ probe, conducted by a team of two dozen reporters, including Webb’s friend Frammolino.

“Reporting by the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times produced no clear evidence of any direct line between the drug dealers and the CIA,” the New York Times noted in a follow-up story.

In May 1997, Jerry Ceppos, then editor of the Mercury News, published a stunning rebuke of the series. “We did not have proof that top CIA officials knew of the [crack-Contra] relationship,” he wrote. He added: “I believe that we fell short at every step in our process -- in the writing, editing and production of our work.”

Almost as a postscript, the CIA concluded a 17-month investigation in 1998, stating that it found no evidence that the U.S.-supported Nicaraguan rebels of the 1980s received significant financial support from drug traffickers.

Webb, who strongly believed his reporting was accurate, told friends that he felt as if he had been abandoned. Some of his colleagues blamed Webb’s bosses for not editing the series more carefully.

“Gary’s flaws were big ones, just as his talents were big ones,” said Herhold. “All along, he needed a strong editor.”

(When reached by phone recently, Ceppos declined to comment.)

The alternative press, which embraced Webb as a hero, blamed the major media, especially the Los Angeles Times, for vilifying him.

“Gary Webb’s work deserved to be taken seriously and to be closely scrutinized precisely because of the scope of the allegations,” Marc Cooper wrote recently in his weekly column for the LA Weekly. “As more-objective critics than The Times have pointed out, Webb overstated some of his conclusions, he too loosely framed some of his theses, and perhaps (perhaps) overestimated the actual amount of drug funding that fueled the Contra war. And for that he deserved to be criticized.

“The core of his work, however, still stands.”

Webb reacted to the heavy criticism by going on radio and television, defending the series. And he continued to do so for the rest of his life. He blamed his editors for cutting important information that backed up his claims.

“The problem is the series was a lot shorter than when I wrote it,” he told one interviewer in 1997. “But as far as what actually appeared in the paper, it’s accurate, it’s truthful and we can substantiate every word of it.”

Life unravels

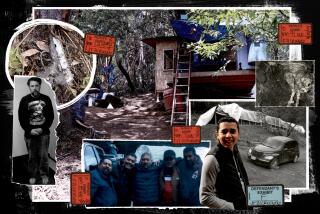

After the CIA scandal, Webb was transferred from his prestigious investigative job in Sacramento and unceremoniously placed in one of the paper’s suburban bureaus. Webb complained loudly. His editors urged him to quit. His colleagues gossiped and joked about him behind his back.

“I wish he had never gotten that call; I wish he would have never gotten that tip,” said Bell, who recalled that Webb carried his resignation letter around with him for two weeks. After he turned it in, he told his wife that he felt like he had just signed his death warrant.

After he left the Mercury News, Webb wrote a book about his CIA findings. The mainstream press largely ignored the 2-inch-thick tome. In his misery and depression, he had a series of affairs. His wife discovered Webb’s infidelities and filed for divorce in 2000. Bell said Webb found himself in a place he always feared: being alone.

He tried to get on with his life, but it wasn’t easy. Searching for a way to put his investigative skills to use, Webb went to work doing special projects and investigations for the state Assembly. He enjoyed the job, but it didn’t compare to newspaper reporting.

He started missing appointments. He lost weight. He wrecked his motorcycles. He stayed up all night playing video games, and he struggled to get up in the morning.

In February 2004, he was laid off from his Assembly job. “He was scared about what he was going to do,” said his ex-wife. Bell, who needed Webb’s help with child support, urged him to go back into journalism. He sent out 50 resumes to daily newspapers across the country. “He didn’t get any offers,” Bell said.

During the summer, a Los Angeles screenwriter called and asked him to collaborate on writing a television miniseries about gun smugglers. In August, Webb went to work as a staff writer for Sacramento’s alternative paper, the News & Review.

Things seemed to be getting better in his life. He produced a number of well-received stories for the weekly paper, and he was excited about the screenplay. But by late September, Webb received word that no one was interested in the television project. He struggled to pay his mortgage and help support his teenage kids on his News & Review salary.

In October, Webb told Bell that he had come up with a plan that would “help both of us out.”

His ex-wife now believes that Webb had been contemplating suicide for most of the year. “He had been distancing himself more and more, but we just didn’t see the signs,” she said.

Secretly, Webb signed over the titles of his motorcycles and cars to his oldest son. He made his ex-wife a beneficiary on his bank accounts. And, in late fall, he bought a cremation certificate.

Webb put his house in Carmichael on the market in November and sold it for $323,000. He promised to vacate the premises by the second week in December.

He was facing the prospect of moving back in with his mother. The night that he died, he dropped a box of mementos off at her house. He told her he didn’t think he had anything left to live for.

That was the last time anyone in his family saw him alive.

The movers arrived at Webb’s house on the morning of Dec. 10. Following his instructions on the note on the door, they called the authorities. Webb’s mother found out her son was dead when she phoned the house later that morning, reaching a coroner’s investigator.

She had the task of telling Bell and Webb’s brother, Kurt, the news.

On Dec. 11, Webb’s suicide notes -- single-spaced and several pages long -- arrived in the mail.

He told his ex-wife and children that he loved them. He also wanted them to know that he did not regret anything he had written during his journalism career.

Of everything he wrote in those suicide notes, Bell said, this point resonated the most: Webb said he was tired of being in pain.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.