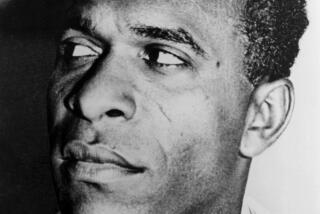

Ba Jin, 100; Chinese Writer’s Faith in Anarchism Helped Fuel Communist Revolution

- Share via

Ba Jin, a giant of 20th century Chinese literature and a staunch anarchist whose writings inspired a generation of youth to join the Communist Revolution, died Monday of cancer in Shanghai, the official Xinhua News Agency reported. He was 100. Ba made it his life’s goal to speak his conscience, but failing health left him unable to speak or write in his last years. His strong anarchist convictions were anathema after the Communist takeover in 1949.

“He was the longest-standing, most influential of China’s anarchists,” said Nanjing University anarchism expert Lu Zhe.

Although he denied it, Ba Jin reportedly was a pen name formed from the Chinese transliterations of the names Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin, the seminal Russian anarchists whose thought deeply influenced his life.

During the first two decades of the 20th century, anarchism captivated China’s intellectual avant-garde, eclipsing even Marxism. Despite debates between the two schools, anarchism helped pave the way for communism’s rise by radicalizing China’s intelligentsia. In talks with U.S. journalist Edgar Snow in 1936, Mao Tse-tung said anarchism had played a profound role in his intellectual development.

Ba’s real name was Li Yaotang. He was born Nov. 24, 1904, near the end of the Qing Dynasty, into a large wealthy family in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. His mother died when he was 10 and his father died when he was 13, and Ba escaped from his sadness into the world of books, memorizing Chinese literary classics and studying English.

At 16, Ba discovered anarchism in Kropotkin’s writings, which he later translated into Chinese, and those of radical feminist Emma Goldman, with whom Ba corresponded. He called Goldman his “spiritual mother.”

Those influences launched his career as a propagandist for anarchy. Though Ba’s writings expressed his genuine convictions, they were standard anarchist fare. He called for revolution and the abolition of private property. He saw patriotism as the root of war. He advocated the use of Esperanto, the universal language, and supported the Industrial Workers of the World, the radical union known as the Wobblies.

He rejected Marxism, saying that its dictatorship of the proletariat was “at its marrow just the dictatorship of a small number of Communist Party members.” He also wrote: “We oppose the Communist Party because it is not communal, not radical and smacks of class compromise.”

Ba’s commitment to anarchism led him to Paris in 1927, where he translated anarchist works into Chinese, published propaganda pamphlets and participated in anarchist activities, including the movement to free Italian labor organizers Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti from jail in Boston. The two were executed in August 1927.

Back in Shanghai and Sichuan Province in the 1930s and ‘40s, Ba wrote his most influential works: the novels “Spring,” “Autumn” and “Family.” The semi-autobiographical “Family,” about a young man’s rebellion against his stiflingly oppressive feudal family, spurred other youths to similar action. During the time they were hiding in the caves of Yanan, Communist officials asked young idealists why they had joined their cause. Many replied that it was because they had read Ba’s novels.

Throughout this period, Ba associated closely with leftist writers and signed their petitions against the ruling Nationalist Party’s persecution of intellectuals. But Ba preferred to remain independent and never joined leftist organizations.

When the Communists took power in 1949, they made Ba a vice chairman of Parliament. Biographer Li Cunguang said that Ba never accepted compensation for this position, relying solely on royalties for income.

Despite his early criticism of communism, Ba was “truly honored” by the Communists’ treatment of him, Li said, and “in the early 1950s, Ba thought he saw the society of his ideals” emerging under Chairman Mao’s leadership.

Ba largely abandoned critical writing about society, instead eulogizing China’s socialist road and producing propaganda in support of the Soviet Union, Vietnam and North Korea. He accepted the party’s drive to ideologically remold intellectuals and purge from among them the corrupt, bourgeois influences of the old China.

In 1954, Ba publicly renounced his faith in anarchism, although many scholars, including Nanjing University’s Lu, believe that in his heart he maintained his anarchist beliefs to the end.

“Everyone who went through it understands that, at that time, nobody dared to say he believed in anarchism,” Lu said.

By the mid-1950s, Mao’s distrust of intellectuals led to political purges. As the head of several official literary organizations, Ba was pressured to denounce veteran leftist authors, starting with Hu Feng, against whom Mao launched a nationwide negative campaign in 1955.

During the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, Ba became a prime target of the Red Guards. They ransacked his home and beat his wife. They maligned him for his previous anarchist writings. The party’s flagship People’s Daily lambasted his works as “anti-party, anti-socialist poisonous weeds.”

The attacks culminated in 1968 in a “struggle session,” in which Ba was put on stage at the Shanghai Acrobatic Arena and maligned for two hours as a “mortal enemy of the dictatorship of the proletariat.” The session became one of China’s first live television broadcasts.

For four years, Ba was confined to the Shanghai Writers Assn. reading rooms, boiler rooms and hallways. Later he was sent to work in rural communes and labor camps. During that time, Ba sometimes sought solace in reading an Italian edition of Dante’s “Inferno.”

Ba returned to Shanghai in 1972 to be with his wife, Xiao Shan, when she died of cancer. As the wife of a “counterrevolutionary,” she had been denied proper medical treatment.

After the Cultural Revolution, Ba gradually resumed his writing and his previous official status.

During the early 1980s, Ba struggled to come to terms with the pain and guilt left over from the Cultural Revolution. In a rambling 900-page series of essays, “A Record of Random Thoughts,” he tried to “dissect himself” using “pen as scalpel” in an attempt to figure out how he had come to deceive and be deceived, to inflict and submit to cruelty.

He said of his criticism of Hu during the 1950s: “I feel disgusted and ashamed of my performance, even though I had no choice about it. Looking at my words of 30 years ago, I still cannot forgive myself.”

His conclusion: Speak the truth.

“When I say speak the truth, I don’t mean an absolute truth or correct words,” Ba wrote in 1982. “What you think is what you say -- that’s speaking the truth.”

Among Ba’s contemporaries, few intellectuals managed to see through the lies and hysteria of the Maoist era until it was too late.

On that score, Ba’s radical views won out over his intellectual and political independence.

Ba was twice nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature. But as a writer, he could not match the biting satire of Lu Xun or the earthy humor of Lao She, two other greats of 20th century Chinese literature. Influenced by Kropotkin, Ba created art not for art’s sake, but as a tool for social change.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.