Joseph Rotblat, 96; Nobel Winner Who Supported Nuclear Disarmament

- Share via

Joseph Rotblat, the Polish-born atomic scientist who quit the World War II Manhattan Project because of his horror at the prospect of nuclear wars and later won the Nobel Peace Prize for work over six decades to promote disarmament, has died. He was 96.

Rotblat died Wednesday in his sleep at his home in London, a spokesman said. No cause of death was given.

Rotblat, a founder and longtime chairman of the pro-peace Pugwash Conference, founded in 1957, was recognized by the Nobel committee in 1995, along with the organization of maverick scientists who campaigned for a world where armed conflict would one day be a memory.

“What we are advocating in Pugwash, a war-free world, will be seen by many as a Utopian dream. It is not Utopian,” he said in his Nobel lecture. “There already exist in the world large regions, for example the European Union, within which war is inconceivable. What is needed is to extend these to cover the world’s major powers.”

Rotblat was derided in establishment circles during much of the Cold War as a dupe of the communists and a fellow traveler because of his willingness to meet with and work for his cause along with Soviet scientists. But, late in his life, Queen Elizabeth recognized him by bestowing a knighthood.

Born in Warsaw on Nov. 4, 1908, to a well-to-do Jewish family, Rotblat studied physics in his native city and was awarded a master’s degree from the Free University in 1932. While earning his doctorate from the University of Warsaw, he went to work as a research fellow and later became assistant director of Poland’s Atomic Physics Institute.

In early 1939, he jumped at an opportunity to study at Liverpool University with James Chadwick, who discovered the neutron. But because his stipend was so small, Rotblat initially left his wife of two years, Tola Gryn, behind in Poland.

In the summer, he returned to Warsaw to take her to England, but she was unable to travel because she had contracted appendicitis. He returned to England without her.

Germany invaded Poland from the west on Sept. 1, 1939, and the country was partitioned by Hitler and Stalin. Rotblat never saw his wife again, and, uncertain of her fate, he never remarried.

“She was obviously dead, but I never knew the circumstances and to me it was still an open book,” he recounted in an interview in 2003 with the Guardian newspaper.

Even before he left Poland, Rotblat had concluded that recent discoveries concerning fission and the ability to split a uranium atom with a neutron had made the creation of an atomic weapon possible in theory. Concerned that German scientists would be working in the same direction, and that England could be put at Germany’s mercy if the Germans succeeded first, he joined Chadwick in a British effort to create an atomic bomb as a deterrent.

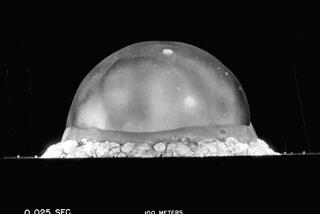

Their British research was later merged with the top-secret American-led effort to create the bomb, called the Manhattan Project, and Rotblat joined the project’s scientists at Los Alamos, N.M.

But when Rotblat learned in 1944 that Germany had abandoned its efforts to make an atomic bomb, he recounted in his interview with the Guardian, he no longer saw a need for the U.S. and Britain to continue.

“I immediately said, ‘Good -- in that case I can resign.’ I hoped that the project would be stopped, but it wasn’t.”

He was the only scientist to resign from the Manhattan Project for moral reasons, and for a while he was under a cloud of suspicion that he had been a Russian spy. But he maintained the project’s secrecy and did not know that a bomb had been successfully completed until he learned of the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima in 1945.

After the war, Rotblat left the field of nuclear physics and began working in medical radiology at the University of London and St. Bartholomew Hospital Medical College. But he also became an early voice of warning against the dangers of the threat of a nuclear conflagration and the possibility that mankind could destroy itself in an atomic war.

In 1955, he and Bertrand Russell appealed to Albert Einstein to lend his voice to the cause of nuclear disarmament, resulting “the Russell-Einstein manifesto.”

The document was signed by some of the world’s leading scientists and declared that atomic weapons could “threaten the continued existence of mankind.”

The manifesto provided the germ for the organization and series of gatherings of anti-nuclear scientists named the Pugwash Conference, after the small Nova Scotia settlement where it first met. It was financed by American industrialist Cyrus Eaton, who had a summer house there.

It opened lines of communication between scientists on both sides of the Iron Curtain and contributed intellectual fodder to the anti-nuclear movement, including early discussions of test bans and anti-proliferation measures.

Among those sometimes attending from the Soviet Union was physicist Andrei Sakharov, who himself later became a leading dissident and moral authority in Russia.

The Pugwash Conference’s current secretary-general, Paolo Cotta-Ramusino, said Thursday that Pugwash owed its existence to Rotblat.

“Jo Rotblat possessed the extraordinary combination of scientific rigor and moral integrity that we believe is, and has been, the hallmark of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs since 1957,” he said.

“Indeed, without Jo, there would have been no Pugwash, and far less pressure from the scientific community on governments to abandon nuclear weapons.”

In a statement he wrote earlier this year to mark the 50th anniversary of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, Rotblat said the landmark disarmament document’s meaning had not dimmed in half a century.

“Fifty years ago we wrote: ‘We have to learn to think in a new way. We have to learn to ask ourselves, not what steps can be taken to give military victory to whatever group we prefer, for there no longer are such steps; the question we have to ask ourselves is: What steps can be taken to prevent a military contest of which the issue must be disastrous to all parties?’ ”

“That question is as relevant today as it was in 1955,” he said. “So is the manifesto’s admonition: ‘Remember your humanity, and forget the rest.’ ”

Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.