Workers at the Door and In the Know

- Share via

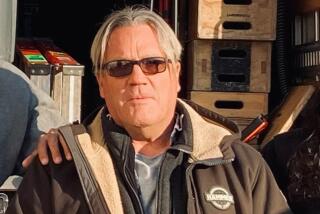

NEW YORK — One of Frank Rappe’s rituals in the building at which he’s worked for 59 years, at 101st Street and Broadway, is creating celebratory signs for special events -- religious holidays, marriages, births -- for his 170 families.

But when the doormen’s union stood on the brink of a strike this week, it looked like he might not get to present his latest artwork, a “Congratulations!” sign he decorated collage-like with lions and tigers for a young couple expecting their first child.

All Rappe needed to learn was the gender, weight and name of the newborn to finish off the gift.

In an equally ritualistic way, the family could be expected to express its appreciation with an envelope containing a tangible thank you and “a note letting me know what they think of it,” said the 83-year-old Rappe, who has been at the Upper West Side building far longer than that couple has been alive.

Of course, had there been no contract settlement, Rappe would have had to picket outside, as he did in 1991, the last time New York’s residential building workers struck, and the management and tenants would not have been allowed to let him inside, even to celebrate a new baby.

“They are not to admit or do ‘favors’ for anybody, especially striking personnel, even if they are long-time acquaintances,” noted a strike Preparedness Manual written by a landlords’ organization. “There are no ‘pals’ or ‘buddies’ during a strike!”

Then the good news came down in the early hours Friday -- the two sides had reached a four-year accord, meaning 28,000 doormen, elevator operators, porters, handymen and superintendents could continue to be “pals” and “buddies” of sorts, albeit in uniform, to more than a million residents of about 3,000 apartment buildings in Manhattan, Queens and Brooklyn.

The pact negotiated with the Realty Advisory Board, which has represented building owners here for 73 years, provides 2% yearly raises for members of Local 32BJ of the Service Employees International Union, who earn an average of $37,300 a year, plus the Christmas-time tips that can add $5,000 to $10,000, depending on the size of a building and the affluence of its residents.

The workers will not have to begin contributing to their health coverage or accept a one-year wage freeze -- landlord proposals that appeared to have left contract talks deadlocked at the midnight Thursday deadline.

But New York’s high-rise dwellers awoke Friday morning to see the familiar faces still at their lobby desks, watching security cameras, hailing taxis and receiving packages and dry cleaning.

The close call served as one of those periodic reminders of the role doormen, in particular, play in the life of the city.

At another Upper West Side building, a co-op a mile from Rappe’s, Phyllis Caroff had been preparing to change her daily habits, as during the last strike, when her husband, Joe, helped gather the garbage and cart it to the curb.

This time, he was going to help cover the door, volunteering for two-person shifts to watch the building’s entrance on 81st Street, across from the American Museum of Natural History, from 8 a.m. to midnight. “He’s too old for the garbage now,” Caroff said of her husband, 84, a retired advertising artist.

Even with those amateur door-watchers, residents were told they’d have to come downstairs to escort any visitors to their units. Other volunteers were going to distribute the mail, another of the services normally covered by the $2,400 monthly maintenance fees paid by co-op shareholders like the Caroffs.

“It takes a lot to keep this building in shape,” said Caroff, a four-decade resident of the building that has two dozen employees, some of whom she’s seen rise from the basement maintenance jobs to lobby positions that require more personal skills, starting with knowing everyone’s name.

“They’re really like members of the family,” she said.

But to Columbia University sociologist Peter Bearman, who has studied the job like few others and written a book titled “Doormen,” that’s one of the tensions of the position, “the problem of intense closeness and great social distance.”

“Doormen know a lot about tenants. They know what they eat, what kind of movies they watch, how often they go out, who their friends are, what kinds of lives they live,” Bearman said. “To do their job, they have to know that.”

But for all the talk of being like family, the doormen are nearly always from another social class from those they serve. When they find the work hard to take, it’s often for that reason, Bearman said. “They perceive the tenants as arrogant,” or worse yet, oblivious -- some look through them, as if they didn’t exist, he said.

Bearman’s survey of hundreds of residential doormen found that they don’t like getting small tips for everyday chores (“they’re not hotel doormen”) and don’t mind wearing a uniform, as long as it “doesn’t make them look like Liberace. Then they perceive that the management is dressing them up like monkeys.”

One other curiosity: Most doormen, even if they could afford it, would not want to live in a “doorman building.” They know how much the doorman sees.

But despite the limited privacy, in the end there’s a substantial -- though subtle -- psychic upside to having a doorman. It is the same “totemic reassurance” suburbanites get when they see the familiar lawn sprinklers or hear the dog barking even before they enter their homes, Bearman said.

Doormen “stand between the building and the street, the harsher environment of the city,” Bearman said.

“They project the building onto the street -- they soften it,” and with a tip of the hat, reassure residents that everything is OK.

*

Local 32BJ describes Frank Rappe as the longest-tenured building worker in New York -- though he did not start out as a doorman.

He began as an elevator operator, after he got out of the Army in 1946, when an uncle who was a porter told him of an opening in the 16-story apartment house at 101st and Broadway. The pay was good, “about $30, $40 a week,” he recalled, but a work week then meant six days, and you had to stand in the elevators -- they didn’t have those little seats for the operator.

Rappe did that for 10 years before he became a doorman and eventually moved nearby, renting not an apartment but a room in the neighborhood where he’s become an institution, eating in the same few restaurants where they know how he likes his meatloaf and roast beef.

The building’s management thought he was ready to retire about a decade ago, but the tenants objected. “So I came back,” Rappe recalled, “as a greeter -- I just greeted the people.” Then they put him at a desk and gave him a new title -- concierge. These days, at 83, he works only on Saturday and Sunday.

How much has changed since he started? Well, not only are the elevators automatic, the front doors are too. They don’t need doormen to actually open them anymore. Where a building like his once needed 40 workers, “now we have, counting the super, six.”

Though he was not scheduled to work Friday, Rappe showed up in the morning to discuss with other workers the settlement reached by their union hours earlier. He decided that they gave a little and got a little: Instead of a one-year wage freeze, their raises will kick in after six months. Rappe had been prepared to walk if the building owners had persisted in demanding that workers pay 15% of their health premiums. Instead, he’ll be back at his desk in the lobby today and working on that sign.

He learned Friday that the young couple just had their baby, a girl. He’d left one square of the congratulatory sign blank, and hopes to have it filled in by the time the mother gets home from the hospital.

“Oh yeah,” he said, “I’ll put in pink for the girl.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.