From a humble start, he found a road to success

- Share via

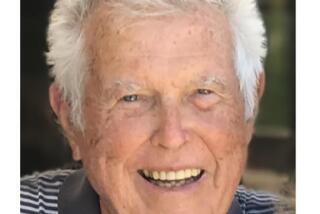

Robert E. Petersen, the self-taught publicist turned publisher and real estate magnate whose fortune gave Los Angeles one of the world’s great automotive museums, died Friday. He was 80.

Petersen’s Hot Rod magazine -- founded when he was 21 -- was the seed for a publishing empire that included Motor Trend and more than two dozen other automotive, hunting, photography, sports and beauty magazines. He died at St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica of complications from neuroendocrine cancer. Friends said his battle with the disease was brief.

Best known for a lifetime immersed in Southern California’s automotive culture, Petersen helped establish the Petersen Automotive Museum in 1994 while a member of the board of directors of the Los Angeles Natural History Museum.

“He helped create and feed the American obsession with the automobile” through his Petersen Publishing magazines and his support of the auto museum, said Dick Messer, director of the Petersen museum.

But as much as Petersen loved fast and beautiful automobiles, he loved hunting and the outdoors more, Messer said, recalling Petersen’s annual safaris in Africa and India. He took the game-hunting and photography trips, often with his wife, Margie, until he was sidelined in 2005 because of an injured back.

A high school dropout who placed gossip tips while working in the MGM Studios publicity office in the early 1940s, Petersen eventually expanded his business interests to include an ammunition-manufacturing company, a jet aircraft charter firm, a Paso Robles, Calif.-area vineyard and a sprawling development business.

He was active in numerous local and national children’s charities, served on the national board of the Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs of America and was a major contributor to the Music Center, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Natural History Museum and the automotive museum that bears his name. He also served on the city’s Library Commission.

Petersen “lived five times as much in one lifetime as most of us do,” said his longtime public relations representative, Joseph Molina.

A head for business

Though he never graduated from high school or attended college, Petersen “was a brilliant businessman,” said Beverly Hills real estate developer and noted auto collector Bruce Meyer, a longtime friend and associate of Petersen. “But he also was humble. He never really realized the impact he had.”

Born in East Los Angeles in 1926, Robert Einar Petersen grew up traveling California’s desert areas with his father after his mother died of tuberculosis when he was 10.

Petersen’s Danish immigrant father, Einar, was a mechanic who worked on heavy equipment for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power in the days when the DWP was stringing power lines into the city from Boulder Dam near Las Vegas.

Petersen attended school in various desert towns, dropping out of Barstow High when he was 15. He scraped plates in a local cafeteria for 25 cents an hour and worked at other odd jobs before moving at age 16 to Los Angeles, where he landed an $18-a-week job as a messenger boy at MGM.

He worked his way up to the publicity department, where his job was to plant items about the studio’s stars with gossip columnists such as Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper.

World War II intervened and Petersen enlisted, serving as a photographer in an Army Air Forces reconnaissance unit. After the war, he returned to MGM and also worked part time snapping baby photos door-to-door.

He was laid off from MGM in the mid-1940s as older, more experienced ex-GIs poured into Los Angeles seeking work. With a number of fellow ousted MGM employees, he started Hollywood Publicity Associates.

“He was looking for clients when he came to see me,” recalled Wally Parks, a co-founder of the National Hot Rod Assn. At the time, 1947, Parks was secretary of the Southern California Timing Assn., a group that sponsored auto racing on the dry lake beds of the Mojave Desert.

The racers, disdainfully called “hot rodders” by many, “needed good publicity,” Parks said, “but I told Bob we didn’t have any money.”

Hot Rod takes off

The two men hatched the idea of holding a hot rod show to promote the sport and show off the hand-built cars as the works of art they believed them to be.

To promote the event, Petersen started a magazine, Hot Rod, using $400 that a friend’s wife had borrowed from her boss.

The magazine debuted in January 1948, with Petersen hawking it for 25 cents a copy on the sidewalk in front of the Los Angeles Armory, where what was believed to be the world’s first hot rod show, another of his productions, was being held.

Bitten hard by the publishing bug, Petersen left Hollywood Publicity Associates to work on the magazine, and he turned the hot rod show over to the PR firm.

Hot Rod spawned the more mainstream Motor Trend magazine in 1949, and Petersen Publishing was on its way.

The privately held company had almost three dozen titles and was operating from a 20-story Petersen-owned building on Wilshire Boulevard in 1996 when Petersen sold a majority interest to an investor group for $450 million.

In 1994, Forbes magazine had declared him one of America’s wealthiest men, with a fortune estimated at $400 million. In 2006, a decade after his putative retirement, the Los Angeles Business Journal estimated that Petersen’s wealth had grown to $760 million.

“He was a self-made, street-smart guy,” said automotive historian and former Petersen museum director Ken Gross. “ ‘Hot rod’ was a pejorative term in the 1940s. Pete had the vision to see hot rodding was more than a bunch of kids racing at the dry lakes and on the street.”

Making money was just a byproduct of Petersen’s zest to do things, Messer said.

The trappings of wealth

Petersen enjoyed what wealth allowed him to do -- he owned 16 Ferraris and scores of other exotic and collector cars and once had the driveway at his 20-room home in Beverly Hills rebuilt with a gentler grade so his low-slung Lamborghini Diablo wouldn’t scrape its bottom. He and his wife bought Scandia restaurant on the Sunset Strip in 1978, and she operated it until they sold it in 1985.

“But he never acted much like a wealthy man,” Messer said. “He was pretty humble and he could laugh at himself.”

He also knew what he wanted and went after it, in his personal life as well as in business. He was 37 when he married Margie McNally, a model with flaming red hair, after proposing on their first date.

The couple had two sons, but in a tragedy Petersen almost never spoke of, both died in the crash of a small plane in the Rocky Mountains during a 1975 Christmas skiing vacation. Bob, 10, and Ritchie, 9, were in one plane and their parents in another for the final leg of their trip. One pilot was able to avoid bad weather in the mountains, but the plane the boys were in crashed.

Petersen told The Times in a 1995 profile that he had never really recovered from the loss but that the deaths helped him grow as a person.

A few years before he sold his publishing business, Petersen spotted an empty building at Wilshire Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue. He thought the former Orbach’s department store would make a perfect home for the Natural History Museum’s growing but undisplayed collection of historic automobiles.

He persuaded the museum board to purchase the structure and launch the museum. He donated $5 million to get it started.

The board named the museum in his honor, and within a year of its 1994 opening the Petersen Automotive Museum was being heralded as one of the finest of its kind.

Financial troubles almost killed it, but Petersen gave $28 million in 2001 to a nonprofit foundation that paid off the debt and now operates the museum. In subsequent years he contributed an additional $5 million to the foundation.

The museum, which has more than 250,000 square feet of display space to show about 120 cars in permanent and temporary exhibits, attracts 175,000 visitors annually. “It is his legacy to Los Angeles,” Messer said.

Petersen is survived by his wife, who requested that instead of flowers, donations be made to the Petersen Automotive Museum or a charity of one’s choice.

A funeral Mass and interment are scheduled for Thursday at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City.