3 U.S. scholars share Nobel

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Three American scholars who study how markets work when buyers and sellers have incomplete information were awarded the Nobel prize in economics Monday. Among the winners was a 90-year-old retired professor from the University of Minnesota who is the oldest person in the history of the prize to become a laureate.

“I really didn’t expect it,” Leonid Hurwicz told reporters who gathered at his Minneapolis home after the announcement. “There were times when other people said I was on the short list, but as time passed and nothing happened, I didn’t expect the recognition would come because people who were familiar with my work were slowly dying off.”

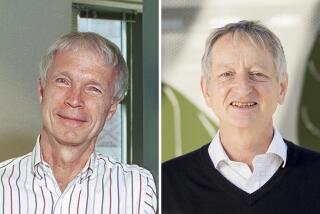

Hurwicz was honored along with Eric S. Maskin, 56, of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., and Roger B. Myerson, 56, of the University of Chicago. The three will share the $1.56-million prize.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences praised the three scholars for laying the foundations of a theory that has led to “major breakthroughs in many areas of economics, including regulation theory, corporate finance, the theory of taxation and voting procedures.”

They analyzed ways to organize markets and other economic mechanisms so they function optimally even when buyers and sellers have access to different information. Their work has been applied to a wide variety of situations, including cap-and-trade systems for reducing carbon pollution and auctions of bandwidth for television and mobile phones.

Traditional economics is based on assumptions that don’t exist in the real world. One such assumption is that all actors in the marketplace have the same information. In the 1960s, Hurwicz began to grapple with the problem of how markets function -- or fail -- when buyers and sellers don’t know the same things.

His co-winners said that in 1972 Hurwicz wrote a seminal paper that described the importance of creating incentives for people to divulge private information that would make economic outcomes more efficient.

“People of my generation -- we pounced on this. Hurwicz had opened something up,” Myerson said at a news conference.

“He changed the course of my life,” Maskin said in an interview.

What Hurwicz pioneered and Maskin and Myerson helped build was a branch of game theory known as “mechanism design”: how to structure systems, including markets, so they include incentives for the kind of information sharing that maximizes outcomes. Those outcomes could include economic goals, such as efficiency, or social goals such as reducing pollution.

Real-world applications of mechanism design theory include deductibles to prevent overuse of insurance.

Hurwicz, a naturalized American, was born in Moscow a few months before the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 to a Polish family, who returned to Poland in 1919. Hurwicz earned a law degree from Warsaw University in 1938, but his interest in economics had been sparked by a course in the subject.

After graduation, he was accepted at the London School of Economics. He was in Switzerland in 1939 when Adolf Hitler invaded Poland, and while his family was interned in Soviet labor camps, Hurwicz emigrated to the United States. He completed his studies at the University of Chicago and Harvard.

Maskin, originally from New York, and Myerson, a native of Boston, both received doctorates in applied mathematics from Harvard University in 1976.

The economics prize is the only one of the Nobel prizes that was not created by Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel. It was established in 1968 and is formally known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

--

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.