Portugal foundation aims for big leaps in research

- Share via

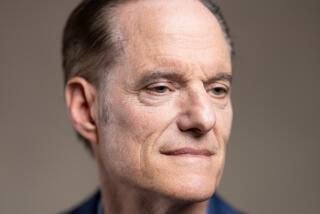

LISBON — When Zachary Mainen told colleagues that he was quitting his job as associate professor at a top U.S. research institute to pursue his career in Western Europe’s poorest country, they were puzzled.

The American neuroscientist swapped Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York for Portugal’s Champalimaud Foundation.

“At first people were surprised I’d do that,” said Mainen, 39, who left his U.S. job in April. “But after they heard what’s going on, they were less surprised. . . .”

The foundation was “offering conditions comparable to what I might have in the U.S.”

A budget crunch in U.S. biomedical research has tightened competition for grants, whereas the fledgling Champalimaud Foundation has $784 million to spend and is courting top scientists with lavish facilities and aims to be a world-class research center.

The private foundation was created by Antonio Champalimaud, one of Portugal’s wealthiest businessmen, after his death in 2004, with an endowment of a quarter of his $3.1-billion estate.

Portugal, with a population 10.6 million, has no tradition of scientific eminence. National spending on research and development is less than 1% of gross domestic product, according to 2005 figures.

That’s below fellow European Union nations’ average of 1.8% and far off the U.S. average, 2.8%. Portugal’s best scientists have long headed abroad for better funding and technology.

Private gifts for science are common in the United States but rare in Europe, where public funds and pharmaceutical companies pay for most biomedical research.

The Champalimaud Foundation’s president, Portugal’s former Health Minister Leonor Beleza, toured leading U.S. schools such as Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to learn how to become a beacon for the world’s scientific elite.

At MIT she met Susumu Tonegawa, winner of a Nobel Prize in 1987 for his work in immunology.

“He said to us, ‘Don’t think you can’t achieve the best, because if you’re ambitious, and the people you choose are rigorous and do good science, you can achieve good results,’ ” Beleza said in an interview.

Beleza focused on two fields where breakthroughs capture public attention: clinical cancer research and basic neuroscience.

Cancer diagnosis and treatment are weak in Portugal, largely because of inadequate screening and the state welfare system’s limited funds, experts say. The Champalimaud Foundation’s high-tech research center, scheduled to open in 2010 at the mouth of the River Tagus in Lisbon, is to feature sophisticated diagnostic and treatment units for cancer patients on the lower floors and research labs above.

That layout is part of a modern trend for healthcare research: a “bench-to-bedside” approach that associates lab developments with real-world situations. Researchers and clinicians are expected to meet not just in exam rooms but at the water-cooler.

The neuroscience program aims to unlock secrets of human behavior by understanding how the brain arrives at decisions. The findings may help decipher mental illnesses such as schizophrenia. The foundation also awards a $1.6-million annual prize for advances in eyesight research.

When foundation scientists eventually move on, they will be allowed to take some of the research funds they raised in Lisbon. Beleza says she doesn’t want her foundation to fall into the common European trap of providing jobs for life, which can stifle progress.

Researchers are also encouraged to travel, because, as she concedes, Lisbon -- near the southwestern edge of Europe on the Atlantic Ocean -- is far from other capitals.

The foundation has snared some illustrious support.

Tonegawa agreed to be on the jury for the annual vision prize.

James D. Watson, the Nobel Prize-winning scientist who helped discover the molecular structure of DNA, is on the foundation’s scientific committee.

Antonio Damasio, author of the 1994 book “Descartes’ Error” and director of USC’s Brain and Creativity Institute, sits on the foundation’s general council.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.