When Detroit drove itself off a cliff

- Share via

The title character in Clint Eastwood’s Motor City morality tale is, by the reaching light of history, a fairly negligible hunk of machinery: a green 1972 Ford Gran Torino Sport, with a sleek “SportsRoof” and a gold “Laser Stripe,” one of many million overfed, undersprung and largely unlamented muscle cars that poured out of Ford, GM and Chrysler factories in the early 1970s. Why not something heroic, a Chevrolet Camaro or Corvette? Why not a Dodge Challenger or even a boattail Buick Riviera? Why did the director (Eastwood again) go with a Gran Torino as the motorized MacGuffin?

Car guys get it.

You could prowl vintage car shows for years and not find an automobile that, in its malign typicality, better summarizes Detroit’s fall than the 1972 Gran Torino. Let’s begin with the thing itself: The car was tubby and it was awkward. It handled like a block of ice with a steering wheel. It lacked even minimum corrosion proofing and so rusted with relish in northern climates. That this oaf of a car should be given the sporty-sounding but nonsensical Italian name Gran Torino -- meaning “great Turin” -- is a bleak joke. (This isn’t the car’s first brush with pop-culture fame: A mid-’70s Gran Torino, with white hockey-stick paint scheme, starred in the TV series “Starsky and Hutch” and the 2004 retread movie.)

The 1972 Gran Torino was one of no less than nine largely redundant iterations of the Torino nameplate, part of a classic Detroit product strategy that attempted to fill every cranny of the segment at the lowest possible investment. That year’s Torino -- “Gran” or otherwise -- also represented a significant retreat in terms of engineering. The previous model-year car was built on a unitized steel chassis, or monocoque, like modern cars. For 1972, the Torino returned to a virtually obsolete and inferior body-on-frame design, which lowered the costs of putting multiple body styles on the chassis.

You could blame Ford’s penny-chiseling management for the Torino’s mediocrity, but you would also have to indict the assembly line. In 1972, Detroit’s unionized workforce was in the full flower of its indifference. Shop foremen battled against even the most common-sense efforts at accountability and quality control. Drug use, absenteeism and even sabotage were endemic. Managers were afraid to walk the factory floors alone.

And 1972 was in many ways an inflection point for the U.S. automakers, the year that Detroit’s mighty cylinders began to seize. The Big Three would never again be as comfortable, and arrogant, and solipsistic, as they were then. The following year’s OPEC oil embargo sent them reeling. It was this generation of cars, which almost seemed to radiate contempt for their buyers, that drove Americans into the embrace of Japanese automakers when they came. It was this generation of carmakers, and indeed the one that came after, that failed to answer the challenges of an increasingly competitive global market. That failure took Detroit -- a once-beautiful city of broad avenues and majestic public spaces -- straight to hell.

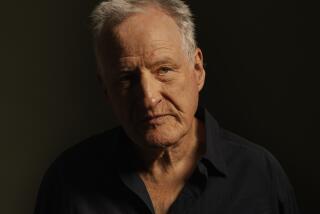

So to say Walt Kowalski’s Gran Torino is a cinematic metaphor doesn’t really do it justice. The car -- to whatever extent it is fractionally responsible for Detroit’s undoing -- is an agent of the film’s action, a prime mover, an original sin. And Walt, a retired Ford autoworker, is an original sinner. One day in 1972 Walt is wrenching away on a Ford assembly line, stuffing a steering box into a shiny Gran Torino before going home to a comfortable middle-class home on a quiet street in Highland Park. Thirty-six years later, he raises the blinds of that same house to discover the world he knew is gone. The jobs have vanished, the factories closed, the prosperity replaced with desperation. How did he get here?

The answer is in the garage.

--