Seeing isn’t always believable in ‘The Eye’

- Share via

“The Eye,” Lionsgate/Paramount Vantage films, released Feb. 1.

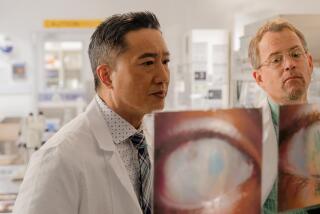

The premise: Sydney Wells (played by Jessica Alba) was blinded in an accident with fireworks at age 5. Twenty years later, because of stem cell research, she is able to undergo bilateral corneal transplants, which are stitched on with large sutures. At first her returning vision is blurry, but as it starts to clear, she suffers from destabilizing visions, hallucinations and dreams. Her ophthalmologist, Dr. Paul Faulkner (Alessandro Nivola), ascribes her visions and anxieties to being bombarded with new images without the knowledge of how to process or assimilate them. Sydney believes she has acquired the paranormal abilities of her donor.

The medical questions: Do stem cells play an important role in corneal transplants? Can both eyes be operated on simultaneously, and are the large sutures depicted in the film realistic? Can vision be restored after such a prolonged period of blindness? Is there difficulty in acclimating to sudden vision? Is cellular memory (in which the donor cells retain characteristics of the donor) possible?

The reality: Adult stem cells are, in fact, used in some corneal transplants, especially when the blindness is caused by thermal injury that has damaged the eyes’ own corneal stem cells. In such injuries, the conjunctiva (the mucous membrane covering the white of the eye) that lies adjacent to the cornea can also be damaged. Repopulating these conjunctiva cells with adult stem cells could make the ultimate corneal transplant successful where it failed before, since the cornea now has more viable tissue to attach to, says Dr. John Hofbauer, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute.

As for having two transplants at the same time, Dr. Roger Steinert, director of cornea, refractive and cataract surgery at UC Irvine, says this is never done. The chance of infection, rejection or poor healing cause doctors not to risk the second eye at the same time. Further, the nylon suture used in such surgeries “is almost invisible to the naked eye. It is only the thickness of three red blood cells.” And whereas Sydney Wells’ sutures are removed soon after the operation, in reality, the sutures are left in for at least six months.

Some long-blind patients are disturbed by their new ability to see; others take it in stride. But Dr. Sanjay V. Patel, an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Mayo Clinic, adds that return of normal vision is unlikely after an accident suffered in early childhood and after so many years. The brain simply becomes unable to interpret signals from the eye, a condition known as amblyopia.

Finally, neither Hofbauer, Steinert, nor Patel knows of a single case in which the recipient of a corneal transplant has taken on the characteristics of his or her donor. This is hardly surprising since they perform eye surgery not in a horror film, but in the real world.

--

Dr. Marc Siegel can be reached at marc@doctorsiegel.com.