Faith in GM bonds has small investors at a crossroads

- Share via

WARREN, MICH., AND LOS ANGELES — Dennis Buchholtz spent a lifetime in the automotive industry, working at companies that supplied parts to America’s automakers. For more than three decades, he spent his days casting iron dies used to turn sheet metal into fenders, roofs and hoods.

He left the business with no pension and no 401(k) -- only an unshakable faith in the ability of Detroit’s Big Three to survive even the worst of economic times.

So when he and his wife, Judy, were weighing how to safely invest their retirement savings, they instinctively turned to the industry’s biggest player, General Motors Corp.

Four years ago, Buchholtz sank about a quarter of the couple’s savings into GM bonds, a decision that followed a long-standing tradition among auto workers to invest in an industry that had afforded so many of them a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle.

For their $98,000 investment, the couple received $7,000 in interest payments each year. It was enough to cover their utility bills, buy some groceries and pay the property taxes on their home -- just three blocks from GM and Chrysler factories. When the bonds reached maturity after 13 years, GM would return their $98,000.

Now Buchholtz’s faith has evaporated along with the couple’s savings.

As the troubled automaker scrambles to slash its more than $27 billion in unsecured debt to avoid a June 1 bankruptcy deadline, the Buchholtzes and thousands of other small investors are finding themselves in an untenable position.

They have two choices: Accept a GM offer to swap their bonds for stock at a loss, or hold out and hope that in a potential bankruptcy, they’ll receive more than the automaker now offers. Either way, they have no hope of getting back their full investment and little say in what happens to the company because they hold a relatively small piece of its debt.

“If this deal goes through, we’re wiped out,” said Dennis Buchholtz, 67, sitting in his living room with Judy, 61. “We’re too old to recoup. Who’s going to hire me?”

The bondholders include former auto workers, schoolteachers, stay-at-home parents and other people who “are financing their retirements, school payments for their children and medical expenses with bonds purchased from the icon of corporate America,” said Amy Noone Frederick, vice president of the 60 Plus Assn., which is helping organize investors.

Small voices

Buchholtz joined dozens of mom-and-pop bondholders in Washington this week to meet with federal lawmakers and see what relief they could get. The creditors plan to discuss their situation at a news conference today and disclose any help they may have been promised.

Analysts say that such people should have been far more wary when they invested their funds, considering the ongoing woes that have roiled the American automotive industry for decades.

But even critics agree that the number of small investors who will suffer is likely to be large. For most companies, individuals represent less than 1% of the debt holders, but as many as a quarter of GM’s creditors are such investors, according to some estimates.

That’s because unlike most companies that issue debt in large denominations, GM sold many bonds with face values of as little as $25, said Shelly Lombard, a bond analyst at debt research firm Gimme Credit. That made them very attractive to average Americans, especially because bonds traditionally promise a steady, safe income.

Considering that the corporation backing the bonds was the world’s largest carmaker for seven decades, many of these small GM bond purchasers say they never even imagined the possibility of risk.

Though their ranks may be large, the total debt they account for is relatively small.

Instead, most of GM’s debt is held by institutional investors and others that specialize in buying highly volatile bonds in hopes of making big profits at low cost. Their vote is key to determining whether GM escapes bankruptcy.

GM’s tender offer

Under the terms of the $15.4 billion in federal loans GM has received, the company must eliminate nearly all of its $27 billion in debt and persuade the United Auto Workers union to trade $10 billion in cash obligations to a retiree healthcare trust for stock. GM must also swap $10 billion of its federal loans for equity.

GM’s solution has been to offer bondholders a 10% stake in exchange for at least $24 billion owed them. The union, meanwhile, would get a 39% stake, and the federal government would get a 50% position. The remaining 1% would go to current shareholders.

Put simply, bondholders would be getting far less value for their investment than the other GM creditors.

The GM tender offer to bondholders expires Wednesday. GM has said that if 90% of the debt isn’t exchanged, it will have no choice but to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, which has the potential to leave the bondholders with nothing.

‘I feel so helpless’

Now, with the deadline looming, the small bondholders are frantically trying to gain a voice in the negotiations.

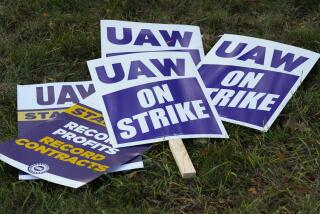

They’ve proposed a counteroffer -- ignored by the automaker -- that would give bondholders a 58% stake in GM. While the director of Recovery for Auto Communities and Workers, a newly appointed advisor to President Obama, toured hard-hit Michigan this month, the bondholders organized petitions. In recent weeks they have held protests in Warren, Mich.; Tampa, Fla.; and Philadelphia.

Mark Modica, a business manager for a Saturn dealership in Doylestown, Pa., already was anxious about keeping his job when he received the proposed plan.

Now he spends his days quelling panic. At work, sales commissions have slowed to a trickle. Customers ask why they should buy a Saturn when GM plans to sell or eliminate the brand. At home, he and his wife have tried to figure out how to rebuild the $150,000 in savings they are poised to lose on GM bonds.

“I can’t afford to accept the offer,” said Modica, 48. “I feel so helpless. I’ll take my chances in Bankruptcy Court.”

That’s a common refrain, as is these investors’ belief that they have been unjustly cast as villains.

When Debra June watched Obama’s recent speech lambasting Chrysler’s holdout creditors as “speculators,” the elementary school substitute teacher felt her stomach clench and her heart race.

It didn’t matter that Chrysler’s investors hold a kind of debt that is different from that of GM’s creditors -- secured versus unsecured. In her mind, and to her friends and family, it was just a Wall Street technicality.

She had been a legal secretary for GM in Detroit from the late 1970s to the early 1980s. A few years ago, she spent about $70,000, half of her savings, on GM bonds. It paid about $5,000 a year in interest -- more than enough to cover the utility and grocery bills for her home in Stuart, Fla.

Losing that, June said, means she must find full-time work. She’s berated herself for not diversifying her investments and has stayed up until dawn worrying.

June, 52, doesn’t know how much her GM bonds will be worth, but the value is sure to be a fraction of what she paid.

At least she found an upside to the 200-plus-page GM plan: It makes a good doorstop.

--

ken.bensinger@latimes.com