Study bolsters concerns that disinfectants create superbugs

- Share via

Disinfectants, be they hand sanitizers or industrial-strength cleaners, present a hospital’s first blockade against bacterial infection. But this same weapon may be helping create stronger microbial enemies: superbugs that are resistant to disinfectants and commonly used antibiotics, scientists report in the January issue of the journal Microbiology.

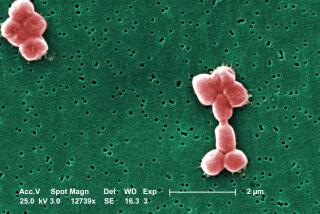

Researchers from the National University of Ireland in Galway studied lab cultures of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which lives in soil and water. The bacterium, which can colonize catheters and other medical equipment, accounts for 8% of infections acquired in hospitals, according to a 2008 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Though it does not seriously hurt healthy people (it’s been implicated in such quaintly named afflictions as “hot tub itch” and “swimmer’s ear”), the bacterium can infect the lungs, joints, burn wounds, urinary tracts and blood of people whose defenses have been weakened by conditions such as chemotherapy, diabetes, cystic fibrosis or AIDS.

In their experiments, researchers exposed bacteria to increasing levels of benzalkonium chloride, an antiseptic used in products such as eyedrops and wet wipes. In the process, they focused on a mutant version of P. aeruginosathat survived extremely high doses of this common disinfectant.

The mutant bacteria were able to survive because they had a more efficient mechanism for ejecting the poisonous chemical, said National University of Ireland microbiologist Gerard Fleming, who led the study. “They’re taking in the disinfectant and they’re kicking it out as fast as they take it in,” he said.

Generally, Fleming said, bacteria only have to possess four or five times the normal resistance level to earn status as a superbug. These mutants, however, were 12 times more resistant to the antiseptic.

Even worse, they displayed a 256-fold increase in resistance to the commonly prescribed antibiotic ciprofloxacin -- even though they had not been exposed to that drug in the experiments.

If hospital workers do not use enough disinfectant for a long enough period of time to kill every last bacterium on a surface, they could be providing an ideal breeding ground for new superbugs, Fleming concluded.

“Absolutely and certainly you must use disinfectant in hospital environments,” he said. “The message, for heaven’s sake, is use disinfectants properly.”

The scientist also expressed concern about frequent consumer use of antibacterials in the home and pointed to a more potent, proven remedy for physically removing germs: “Soap and water. I am not messing with you.”

Further study is needed on other common hospital-acquired pathogens to see whether they have superbug potential as well, Fleming added. “We need to repeat this on other organisms. Two I would go for is MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] and Clostridium difficile. . . the new bug, the new killer in hospitals.”