Time’s Up has kept #MeToo in the spotlight and raised $22 million. Now it wants leadership and focus

- Share via

Bound by fury, 300 women in entertainment came together last fall in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein sexual harassment scandal to form a loose-knit coalition with big ambitions.

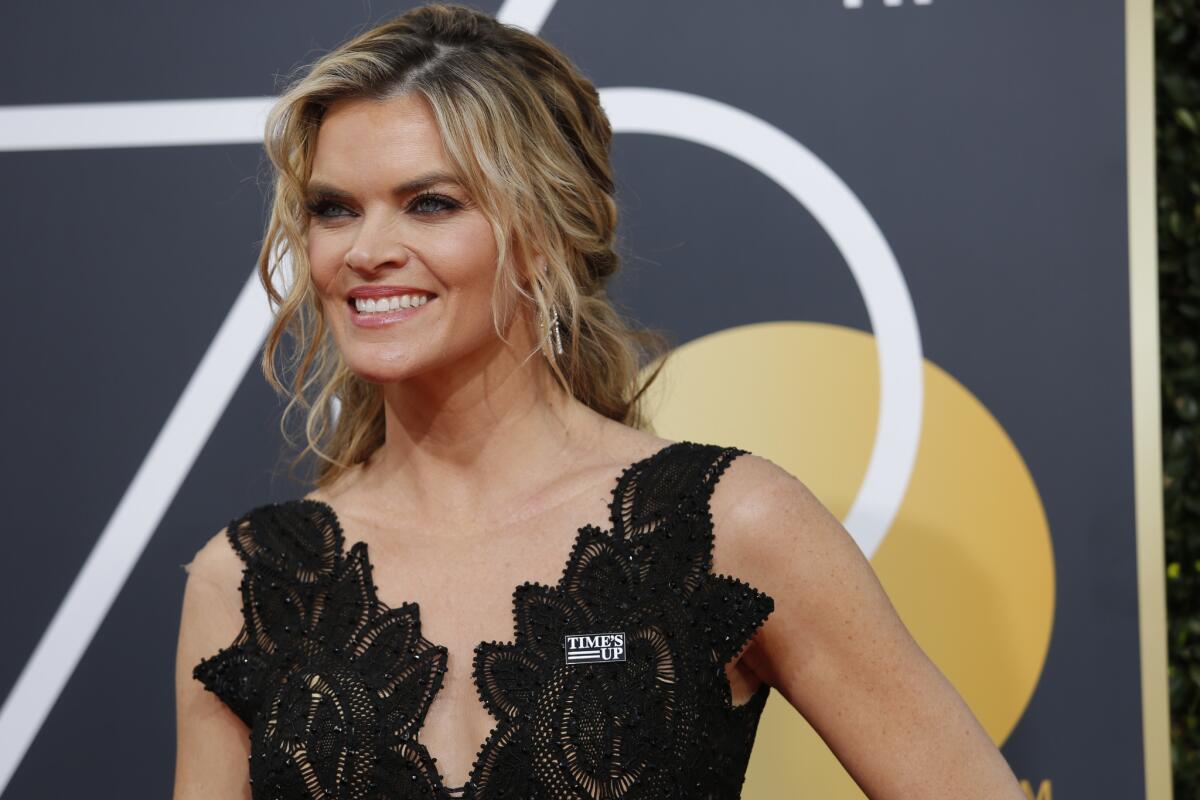

The group quickly raised $12 million and vowed to fight discrimination and sexual harassment by giving voice and support to those who have suffered abuse. It took out “Dear Sisters” newspaper ads and staged a dramatic “blackout” at the Golden Globes Awards show, with A-list actresses and TV and movie producers dressed in a monochromatic display of unity. Oprah Winfrey used her speech that January night to condemn “a culture broken by brutally powerful men” and repeat the organization’s undeniably catchy name, Time’s Up.

“For too long, women have not been heard or believed if they dared to speak their truth to the power of those men,” Winfrey said. “But their time is up.”

Nearly one year in, however, confusion persists about the mission and inner workings of Time’s Up.

The organization has raised more than $22 million, much of it coming from big names in Hollywood, for a legal defense fund that has provided assistance to dozens of women. But efforts to shift the balance of power — and demand that institutions listen to the voices of women — largely have fallen short, even during the contentious confirmation of Brett M. Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court. Beyond the image of actress Alyssa Milano silently sitting behind the nominee during a Senate hearing, its efforts were ignored. A day after the testimony by Kavanaugh and his accuser, Christine Blasey Ford, Time’s Up co-sponsored a protest at Los Angeles City Hall. It drew a sparse crowd.

Several groups came together last fall as women shared #MeToo stories of abuse. One, the Commission on Eliminating Sexual Harassment and Advancing Equality in the Workplace, is led by Anita Hill — who became a public figure when she accused then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of harassment. But with its invigorating name and star power, Time’s Up overshadowed the others; indeed, it was often considered synonymous with #MeToo, which remains a movement rather than an organization.

Initially fashioned as a democratic collective, the organization prided itself on not having a single leader, typically speaking through an unsigned statement. Announcements of smaller groups — Time’s Up Technology, Time’s Up Entertainment — and other areas of interest such as helping female farmworkers and promoting film critics of color, only added to the confusion.

“It’s never been clear what Time’s Up is,” said one attorney who has worked with the group. “We don’t even know who Time’s Up is.”

The group appeared to realize some of the problem; earlier this month, it was announced that Lisa Borders would be leaving her job as president of the Women’s National Basketball Association to become president and CEO of Time’s Up. When a few reporters were hastily summoned to a news conference to meet her, the sense of relief among other group members was clear.

“It is very difficult to sustain social movements over time,” Borders acknowledged later in an interview. “You cannot be inattentive, you must continue to be vigilant.”

Already the group has certainly changed, or highly influenced, the wave of outrage unleashed by multiple allegations of sexual harassment made against dozens of high-profile men in the last year.

“To say that we did not know what we were launching was an understatement,” Rebecca Goldman, the chief operating officer, said recently. “We literally ordered 300 T-shirts and 500 lapel pins. We did not know if anyone would want them. What happened was this incredible outpouring of women … calling us, coming together, wanting to mobilize.”

Even some Democratic members of Congress, including House minority leader Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco), sported the lapel pins during President Trump’s State of the Union address. Seven full-time staff members were hired with seed money from two of the co-founders, television producer Shonda Rhimes (“Grey’s Anatomy”) and producer Katie McGrath, who runs Bad Robot Productions with her husband, J.J. Abrams.

Early on, the energy was electric and meetings were massive, and often unfocused.

In Hollywood, where gatherings were held at the homes of actresses including Eva Longoria and Brie Larson, there were debates between women who had spoken out against high-profile men and those who had not. Sometimes, these discussions continued on a What’s App text chain that included dozens of high-profile celebrities like Jennifer Lawrence and Emma Stone.

In one meeting before the group made its public debut in January, a few members began drafting an “enemies and allies” list so they could zero in on executives whom they viewed as not supportive of women, according to one participant. Some demanded that Time’s Up dictate who would be hired to lead Amazon Studios after its former chief, Roy Price, was sent packing in a harassment scandal. A discussion in Lifetime Television network’s New York offices dissolved into vitriol over Bill Cosby (before his conviction), according to another group member who also was not authorized to comment.

“There were varying levels of irateness,” she said. “It was like having a meeting of 200 members of PETA. And while you are trying to come up with a strategy, someone stands up and says: ‘My local restaurant has rabbit on the menu, and I think it is terrible. Should we call the police?’

“Things got in the weeds very quickly.”

One member equated the leaders’ attempts to corral members during meetings to herding cats.

Goldman took issue with that characterization.

“It was actually a really informed, strategic process to gather feedback, to gather opinions,” she said. “We have done that groundwork of listening, learning and examining so that we can turn it into action.”

Roberta Kaplan, a prominent New York attorney, was more blunt.

“We needed a leader,” Kaplan said. “We want this thing to not just be words and talk and slogans, we want it to result in real concrete action. In order for that to happen, we have to have a structure with leadership.”

Caroline Heldman, an associate professor at Occidental College who has become a leading advocate for victims of rape and other sexual assault, said Time’s Up has done a remarkably good job with two things: “They have helped keep the #MeToo movement and the issue of sexual violence in the national agenda. And they have raised a lot of money for the legal fund, which goes beyond the women of Hollywood to help people in other industries.”

“It is very difficult to sustain social movements over time.”

— Lisa Borders, Time’s Up CEO

Money has poured in. Major talent agencies, including some tarnished by accusations of abetting Weinstein and others, forked over million-dollar donations. Steven Spielberg and his wife, Kate Capshaw, through their foundation, contributed $2 million. Abrams and McGrath donated $1 million. Reese Witherspoon, Meryl Streep, Jennifer Aniston and Sandra Bullock each chipped in $500,000.

Time’s Up turned to the National Women’s Law Center in Washington to administer its legal defense fund.

“We pivoted into something that would be a real demonstration of sustained support for women who don’t have the visibility that women in Hollywood do,” McGrath said.

Or the money.

Many women have said they kept silent about sexual harassment over the years for fear of being crushed by a man who had access to powerful lawyers.

Kaplan said she received a call in early November from Christina Tchen, a Chicago attorney and former chief of staff for Michelle Obama. Movie producer Brett Ratner had filed a defamation lawsuit against a woman in Hawaii who wrote on her Facebook page last October that he had raped her.

Ratner, who continues to deny the accusation, withdrew the defamation suit this month. Still, the ramifications were enormous.

“We saw [her] case as the beginning of a wave,” Kaplan said. “Women [were] sued to stop them from talking. … There was no upside for a lawyer to take that case, but we needed lawyers to protect these women.”

Since January, more than 3,500 people, including individuals from all 50 states, have asked for help through the legal defense fund. The group has agreed to finance at least 51 legal cases, and so far about $4 million has been spent on legal and public-relations assistance.

Time’s Up also provided $750,000 for community grants to 18 organizations, including the YWCA of Greater Los Angeles.

“We’ve been focused on low-wage workers,” said Sharyn Tejani, who is director of the legal defense fund. “And we have seen that in almost every case, there is a claim of retaliation. If they complain, they are told there is no work for you, or their shifts get cut. That makes it incredibly difficult for people to come forward.”

Tejani’s group connects individuals with one of the 780 lawyers who have joined the legal network. Each has agreed to provide at least one free consultation, and they often take on the cases for free.

Jackie Len, an employment attorney with Endeavor in Beverly Hills, volunteered to help Annie Delgado, a teacher in Merced who had been fighting her school district after a boys basketball coach allegedly slapped her on the buttocks and made lewd comments at a 2017 school function.

There was an investigation, and the coach received a reprimand. Then the school district honored the coach to mark his 400th win. Delgado said that celebration, as well as being belittled by a school administrator for reporting the incident, made her feel like she was the one being punished.

“I was drowning. One day I sat down and asked for help,” Delgado said. “I remember thinking that if this doesn’t work, then I have nothing.”

Her association with Len, who has volunteered more than 50 hours of her time, has resulted in changes. Together, the two women have pushed the district to strengthen its sexual harassment policies.

“I just remember crying — I was so grateful,” Delgado said of Len’s help. “In some ways, this has been a life preserver. I felt like I was finally being heard.”

Staff writer Amy Kaufman contributed to this report.

Twitter: @MegJamesLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.