California has big gaps in distribution of high-skill industries

- Share via

California has one of the nation’s largest concentrations of “advanced industry” workers, but a new study points out that the state still faces big challenges in Stockton, Fresno, the Inland Empire and elsewhere.

The study from the Brookings Institution zeros in on clusters of high-skill industries such as those in Silicon Valley, saying they are critical to raising the standard of living and attracting wealth in major cities. They offer better pay for workers and create products that can be sold across the world — not just down the street.

The distribution of such high-value jobs — which pay an average of $90,000, nearly twice that of other industries — varies widely across the state.

The San Francisco, San Jose and San Diego metropolitan areas, for example, had some of the largest shares of technically skilled workers in the country — all ranking in the top 10 of the largest 100 U.S. metro areas.

The state also figured prominently at the bottom of the list in places including Fresno and the Inland Empire, the study found. Los Angeles and Orange County fell right in the middle. They were ahead of Chicago and New York City, but far behind cities such as Boston.

All cities approach these challenges differently, said Mark Muro, a policy director at Brookings who co-wrote the report released this week.

“Not all industries or jobs matter in the same way, and these are the industries that matter more,” he said. “This is the way in for new resources, new spending and new income to the U.S. economy.”

The analysis defined “advanced industries” as those that spend a significant amount on research and development, and employ workers with higher-than-average skills in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. It encompasses a wide array of professions, from management consulting to computer systems design to aircraft parts manufacturing.

The sector is responsible for 60% of U.S. exports and has led the way in job creation since the Great Recession, expanding at nearly twice the rate of all other sectors combined since 2010.

But the growth is happening in far fewer areas than in the past. Only 23 large U.S. metropolitan areas have more than 10% of their workforce in advanced industries, compared with 59 in 1980.

The changes can perhaps best be seen locally in the differences in the ways that Los Angeles and San Diego have developed over the last few decades.

In 1980 the Los Angeles metropolitan area, which includes Orange County, was one of the nation’s leading hubs for high-tech production, led by aerospace manufacturing. At the time, more than 16% of the area’s workforce was employed in industries involving engineering, science and research.

Since then, as the center of gravity for aerospace and military shifted to the nation’s capital, the Los Angeles area’s share of advanced workers has dipped to 9%.

“The resilience of the economy depends on finding new industry jobs to replace those old ones,” said William Yu, an economist with the UCLA Anderson Forecast who specializes in the Los Angeles economy. “But we didn’t achieve that. So a lot of people just leave. They had high skills, high education, and they leave for another place, or they retire.”

San Diego, by contrast, has moved in the opposite direction, expanding its share of skilled workers over the last three decades by building one of the nation’s largest research and development centers specializing in life sciences and biotechnology.

The Torrey Pines Mesa near UC-San Diego is home to more than 500 companies specializing in genetic research and drug development, where fresh start-ups partner with university researchers to create new products for improving human life.

Kleanthis Xanthopoulos has helped grow four companies from scratch in the area since 1997. At his current company, Regulus Therapeutics, he focuses on gene therapy to treat disorders ranging from fibrosis to Hepatitis C.

Just because of the proximity to other companies in the field, he said he is regularly able to interact with other executives without even scheduling a meeting.

“Just stepping out to go to lunch, it’s almost certain that you’re going to see other CEOs or chairmen of the board right there,” he said. “I get the chance to hear about challenges, opportunities. That’s priceless.”

The success of San Diego’s life sciences cluster sprung from expertise honed at UC San Diego and other institutions such as the Scripps Research Institute. But the industry grew out of a concerted effort to take research ideas borne in laboratories and make them commercially successful. Consortiums such as Connect, a trade association originally formed at UCSD, focus on bringing seasoned business executives, entrepreneurs and researchers into constant communication.

“Even with the Internet and Twitter and all these tools we have, people like to be in close proximity to work on projects, start new companies and commercialize new technologies,” said Greg McKee, the chief executive at Connect. “The base principle of it is that you need to have a critical mass of people around certain types of activities to make all this go.”

In Los Angeles, experts said, there hasn’t been the same kind of density in technical professions such as science and engineering.

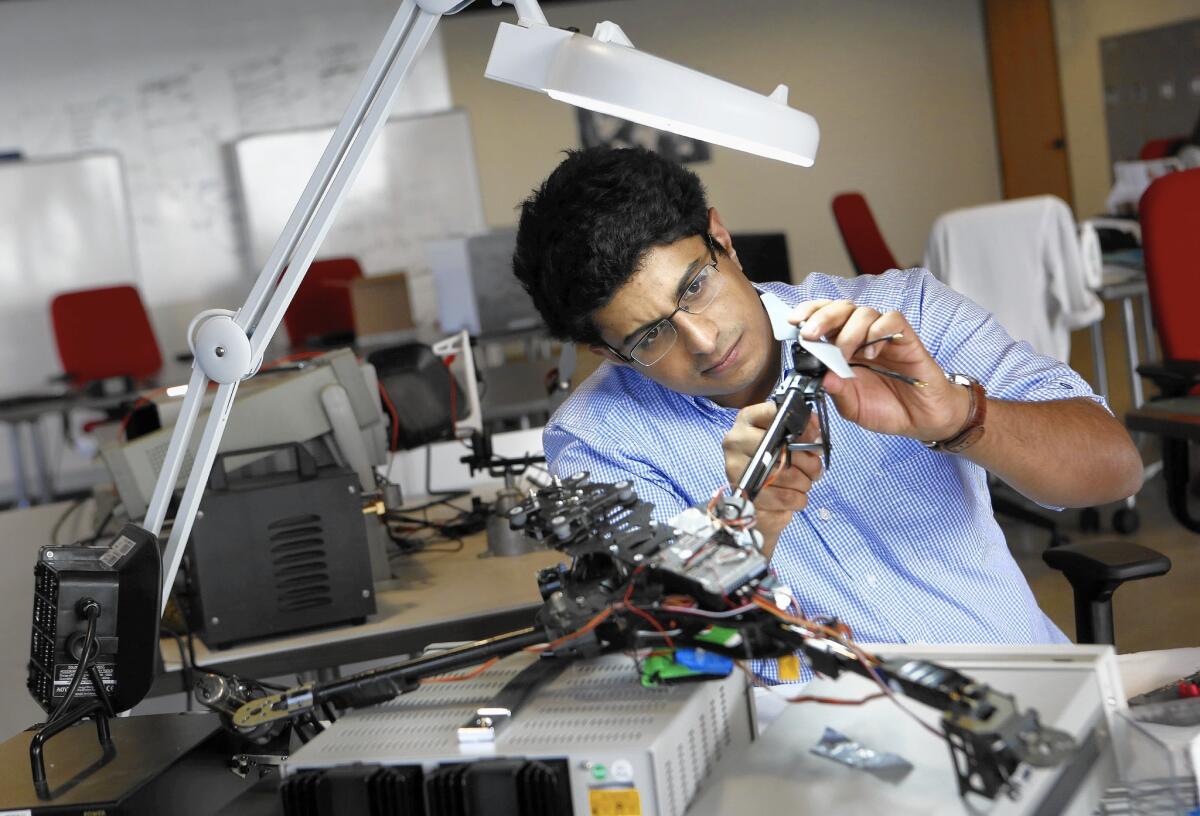

Some is taking hold in corridors such as Santa Monica, Venice, Marina del Rey and El Segundo, where major tech companies such as Yahoo and Google and setting up shop next to more recent entrants including Tinder and Snapchat. But the problem is convincing engineers that Los Angeles is where they will learn the most, said Ashish Soni, an associate professor of engineering at USC.

“How does a non-engineering economy continue to attract engineering talent?” Soni said. “In L.A. the people who have the most influence are the people in the media business. A top engineer is not going to have that same visibility in the region yet. But that’s where I think change is coming.”

Brandon Angelo grew up in the Bay Area, in the shadow of Google, and always figured he’d work as a programmer developing the next greatest software application. But after he graduated from USC and worked as a programmer in Silicon Valley, he grew anxious to return south and pursue a new idea: self-guided personal drone cameras.

Angelo grew up loving radio controlled aircraft and was attracted to the aerospace expertise still in the region, along with the success of Elon Musk and SpaceX.

His startup, Awesome Sauce Labs, is building a drone that automatically follows users around and takes pictures. “It becomes the ultimate selfie rod,” he said.

Though he acknowledges that programming talent flocks to the Bay Area, he said the engineering programs at USC, UCLA and Caltech offer an enormous pool of talent that approaches technology in a different way.

“I was personally more interested in building something real,” he said. “You have people down here who still have that nerd cred, but are also interested in physically building things, having a really good product that’s more than just software.”

Twitter: @c_kirkham

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.