This Hawthorne company finds security in border protection

- Share via

The man who forever altered airport security checks is an unassuming type who likes to chat up TSA officers in his spare time.

“When I have to fly, I try to get there a little early and I talk to the screeners,” said Deepak Chopra, an engineer who shares a name with the holistic living guru. “I really want to know. ‘How are my machines doing? How are they performing?’”

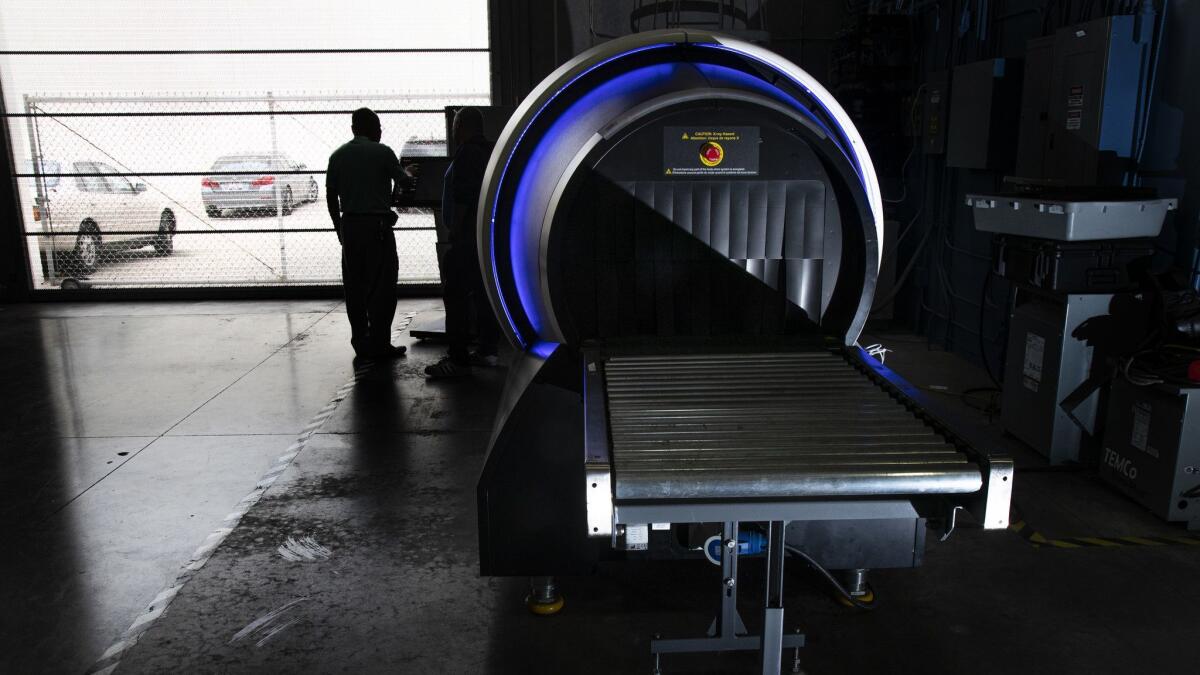

Chopra is chief executive of OSI Systems Inc., a Hawthorne company that makes many of the luggage and passenger scanning machines found at airports, harbors and other security checkpoints through its Torrance subsidiary, Rapiscan Systems. The company had a brief brush with notoriety a few years ago when its full-body passenger scanners — nicknamed “nudie scanners” by some critics — generated safety and privacy concerns for the X-ray technology used and the supposedly revealing nature of the images.

But the controversy was a brief blip for OSI, which has vaulted to the forefront of the rapidly growing threat-detection industry.

In the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks, security has boomed, with the sales of threat-detection systems alone expected to increase to $119 billion by 2022 from $48 billion in 2015, according to business research firm MarketsandMarkets.

Nick Vyas, executive director for the Center for Global Supply Chain Management at the USC Marshall School of Business, said the drive for added security will only intensify.

“This has now become the way of life for us,” Vyas said, “meaning we somehow will always consider the reason we haven’t had anything like 9/11 again is because all of the security we have put in place. Scanning equipment is an example. That will continue for a long period of time.”

In April, OSI posted quarterly revenue of $304 million, its highest ever in a three-month period. The company, which also operates divisions that make medical diagnostic equipment and electronic components, closed Friday $117.03 a share, a record high.

The security division produced nearly two-thirds of OSI’s $1.09 billion in fiscal 2018 revenue, and the operation’s revenue grew 24% from the year before. So far this year, OSI has announced significant new business including orders from the NATO Support and Procurement Agency and the Australian government for OSI equipment to detect weapons and other contraband in luggage, mail and cargo containers.

Other deals announced this year include parcel checkpoint inspection systems for U.S. correctional facilities and detention centers, explosives and narcotics trace detection systems for a European airport and cargo screening systems in Guatemala.

“We are an international company with manufacturing in Malaysia, Indonesia, England, and Edinburgh, Scotland,” Chopra said. “We have more than 100,000 machines installed worldwide.”

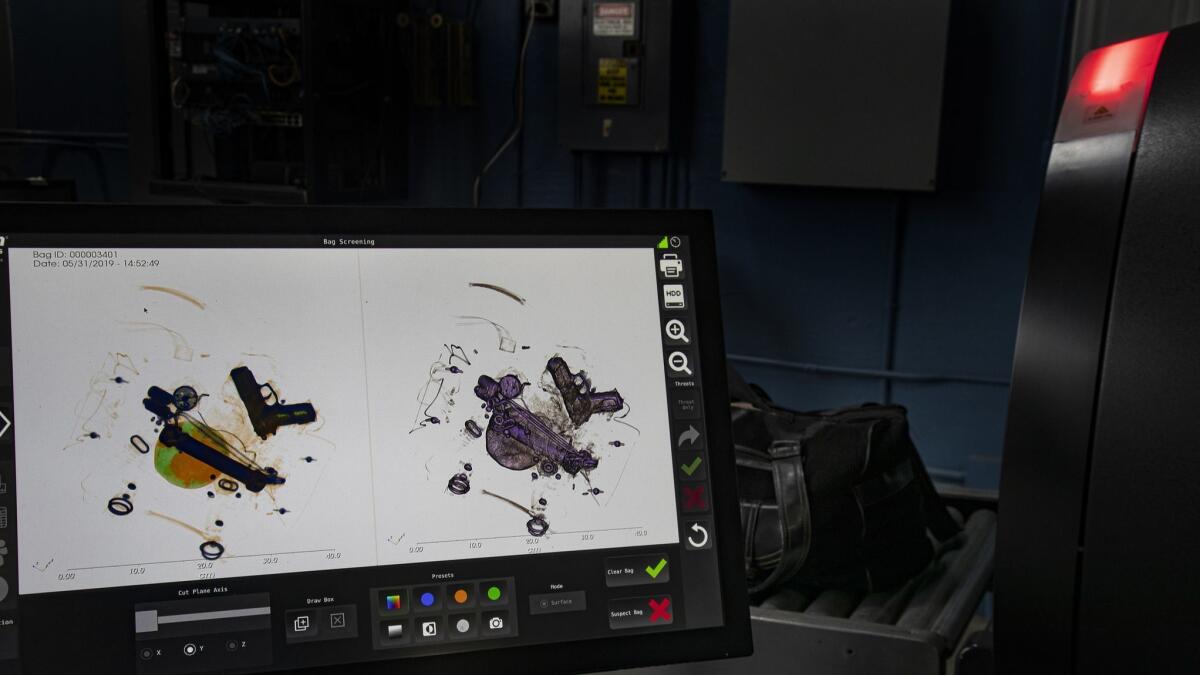

In January, U.S. Customs and Border Protection announced its largest ever border seizure of fentanyl, along with a substantial cache of methamphetamines, from a produce truck at the Nogales, Ariz., crossing.

An OSI cargo scanner turned up the drugs, worth about $5 million, by detecting a secret compartment hidden beneath a load of cucumbers.

“These are professional drug dealers who are intelligent,” Chopra said. “Very intelligent, well-funded bad guys. A wall is not going to stop them. Technology will stop them.”

Although package delivery company DHL Express, a Rapiscan customer, uses a variety of screening equipment from different companies, “we do find that Rapiscan provides us with the product quality and reliability we need to keep our network operating at the optimum efficiency,” said Simon Roberts, DHL’s head of global security compliance.

That kind of success represents a comeback from controversy over a particular model of passenger scanners deployed in 2010. The machines, called Secure 1000s, used low levels of X-ray radiation to peek through clothing. Rapiscan manufactured 211 of the 385 image scanners that were once in use at 68 airports nationwide.

But the devices quickly came under criticism. Some thought the images created were too revealing. Radiation effects were also feared, although the company said at the time that a passenger would have to pass through one of its scanners 1,000 times to receive the equivalent dose of a dental X-ray.

In a 2011 interview with The Times, Chopra provided this defense of the full-body scanners: “The machine cannot store images. The person checking the screen is in a different location and cannot see the person who is on the screen. Look at the alternative: You’re spread-eagle and somebody is feeling you everywhere.”

In 2012, OSI’s stock took a hit after the House Transportation Security Subcommittee chairman said Rapiscan may have manipulated government tests for the scanner. OSI said the government controlled the tests and that manipulation was impossible.

The next year, those scanners were removed from airports after Rapiscan couldn’t install software required to protect the privacy of passengers in time to meet a congressional deadline. The financial significance of the controversy was minor, even though competitors gained some of those contracts, company representatives said.

Full-body scanners in use at U.S. airports today must comply with a 2013 law, prompted by the Rapiscan furor, that requires such machines include privacy software filters that keep the devices from showing details of a traveler’s body. A person being scanned generally appears as a generic avatar or a blob, and the advanced imaging technology no longer involves X-rays.

OSI, which employs more than 5,000 people, came about almost by accident.

After having worked for several large tech and defense firms, including an optical sensor maker, Chopra was looking for new opportunities and was considering investing his savings in Del Taco franchises. His wife, Nandini, thought it a terrible idea. She won the argument.

Instead, Chopra invested in a tech start-up that made something he knew more about than tacos: optical sensors. The start-up eventually became OSI, with Chopra in charge.

In 1992, the company bought Rapiscan, a big buyer of Chopra’s old company’s sensors that was having trouble paying its bills.

Chopra didn’t foresee the security boom so much as embrace the opportunity to create “a vertically-integrated supply chain from components to end products, giving us flexibility and speed to market that others can’t match.”

Chopra closely follows the performance of his company’s machines, especially when they are linked to news events like a record drug bust.

“It gives me goosebumps,” Chopra said. “It helps me sleep well.”

For more business news, follow Ronald D. White on Twitter: @RonWLATimes

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.