A merger with Port of L.A.? No way, Long Beach officials say

- Share via

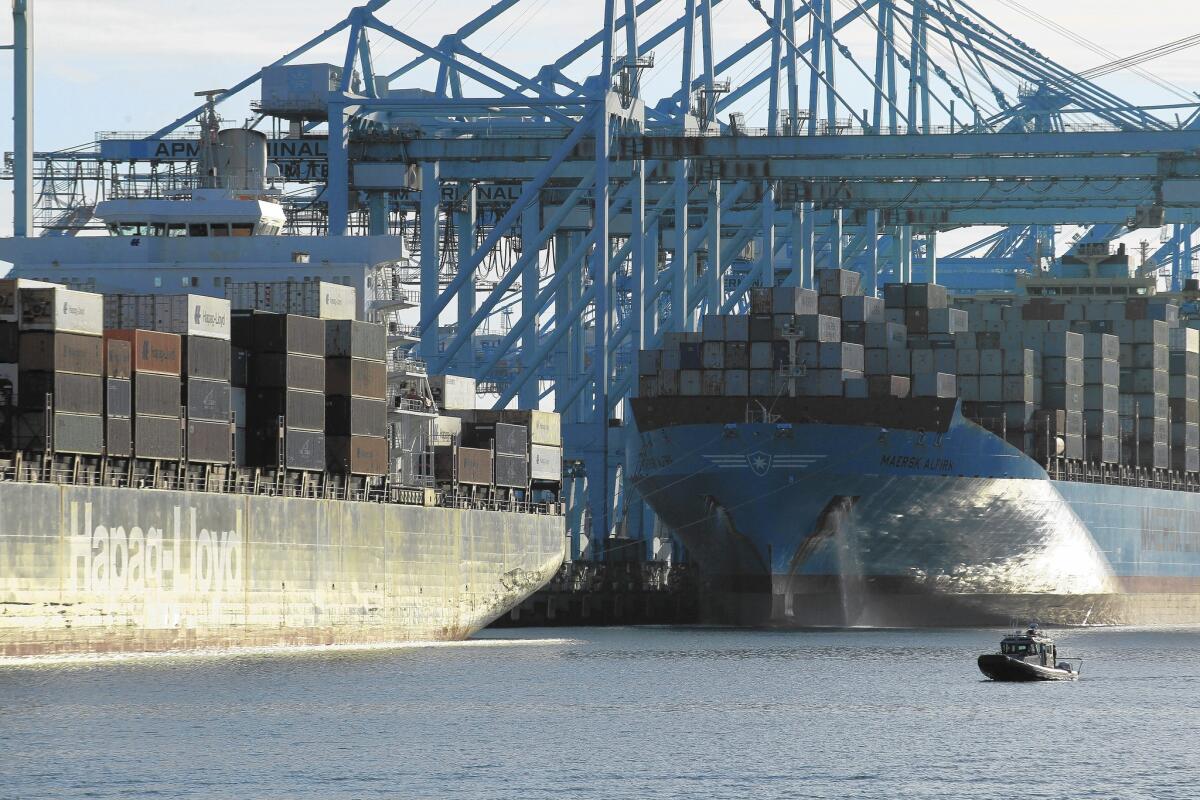

The ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are like the Coke and Pepsi of U.S. maritime transportation.

They seem similar, they dominate the competition but they have a long history of less-than-friendly rivalry. Now, an independent commission’s proposal to merge the neighboring harbors is being met with skepticism.

The L.A. 2020 Commission, made up of prominent business, labor and civic leaders, on Wednesday unveiled a series of recommendations that included merging the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

But the proposal appears to have landed with a thud among Long Beach officials.

“Simply put, this is a bad idea,” said Doug Drummond, president of the Long Beach Board of Harbor Commissioners. “The Port of Long Beach is not interested in a merger with our neighbor.... I can assure you that the Port of Long Beach is better run by the citizens of Long Beach.”

In its 18-page report, the 2020 Commission said that a merger makes sense because of a drop in market share at the ports of L.A. and Long Beach, the busiest seaports in the U.S.

In the last 10 years, the ports’ combined market share fell more than 5 percentage points, the report said. The ports operate as landlords to the shipping lines, which move millions of cargo containers full of products in and out each year.

“That drop in market share alone is the size of the fifth-biggest port in the country, Seattle-Tacoma, which accounts for more than 60,000 jobs and has in excess of $100 million in revenue,” the commission said. “We should fight to bring those jobs and tax revenues back to Los Angeles.”

The neighboring ports, which have operated separately for decades and have been known to poach each other’s tenants, currently handle about 40% of U.S. imports. The two account directly for about 595,000 jobs in the region.

But the ports face the looming threat of a $5.2-billion expansion of the Panama Canal, which would enable larger ships to pass through the canal. That upgrade might disrupt existing routes and shift business to ports on the East and Gulf coasts, which have been expanding in anticipation of the work’s completion.

To fend off that threat, the L.A. 2020 Commission said, the ports should work together as one. It pointed to examples of regional cooperation at the ports of Seattle and Tacoma, as well as by New York and New Jersey officials.

“We should be competing with ports in other regions, not with each other,” the report said.

Outgoing Long Beach Mayor Bob Foster bristled at the recommendation and said that no one from the 2020 Commission had sought input from his city.

Foster questioned the idea of a port merger, saying that in the past, the city of Los Angeles had approved harbor projects that disproportionately affected neighborhoods in his city.

Long Beach, for instance, sued Los Angeles last year over a $500-million rail yard planned by BNSF Railway Co. The rail yard was approved by Los Angeles city officials, but Long Beach objected, arguing that the rail yard would be directly adjacent to Long Beach neighborhoods and diminish the air quality.

Los Angeles officials have said the rail yard would be “greener” and would reduce air pollution in the area.

Long Beach was treated “very poorly by the port and the city of Los Angeles,” Foster said.

Across San Pedro Bay, the Port of Los Angeles appears to be more amenable to discussing a merger. The port said it welcomes “the opportunity to discuss additional collaborative efforts that would both retain and expand the existing cargo and jobs at the San Pedro Bay port complex,” said Phillip Sanfield, a port spokesman.

“The two ports have a strong track record of working together on a wide range of initiatives related to the environment, security and efficiency improvements,” Sanfield said.

The commission said it relied on data and interviews with people who do business at the ports.

“Of course, the people of the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles aren’t going to endorse the idea of a merger,” said Austin Beutner, co-chair of the commission. “They’re going to fight for their turf.”

The international shipping lines and major retail chains that send cargo through the ports are maintaining a diplomatic silence on the matter, declining to comment for publication.

John McLaurin, president of the Pacific Merchant Shipping Assn., which represents tenants and customers at the twin ports, said the group hasn’t taken a position on the proposed merger.

But one longtime port observer, Manny Aschemeyer, a consultant on port issues who began his career at the ports in the 1970s, said clients and other users of the harbors may oppose a merger.

“There is a benefit to having two separate controlling agencies,” said Aschemeyer, former director of the Marine Exchange of Southern California, which tracks ship movements at the ports. “It keeps them balanced in terms of charges and fees and services. And frankly, even though they’re living right next door to each other, they’re fiercely competitive.”

A port conglomerate, he said, could mean higher rates and fees. The two ports have typically been reluctant to raise fees for fear of losing a client to the competing port.

Economist John Husing, who keeps a close eye on the Inland Empire’s port-dependent warehouse industry, said the concept of one mega-port is unlikely to gain traction.

“The public benefits from competition between them,” Husing said.

Jock O’Connell, an international trade economist who follows the ports, said a merger is worth considering.

Entering an agreement to work together, O’Connell said, could combine marketing efforts, potentially saving money and presenting a stronger united front. It could also make it easier for a consolidated port authority to fend off competition from other ports.

But O’Connell warned that it would be a “politically difficult task” to get the two ports to agree to a merger. That route, he said, is “fraught with political uncertainties.”

Twitter: @rljourno

Times staff writers James Rainey and David Zahniser contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.