Trump removed Wall Street’s secret shackles. Now banks are prowling for deals

- Share via

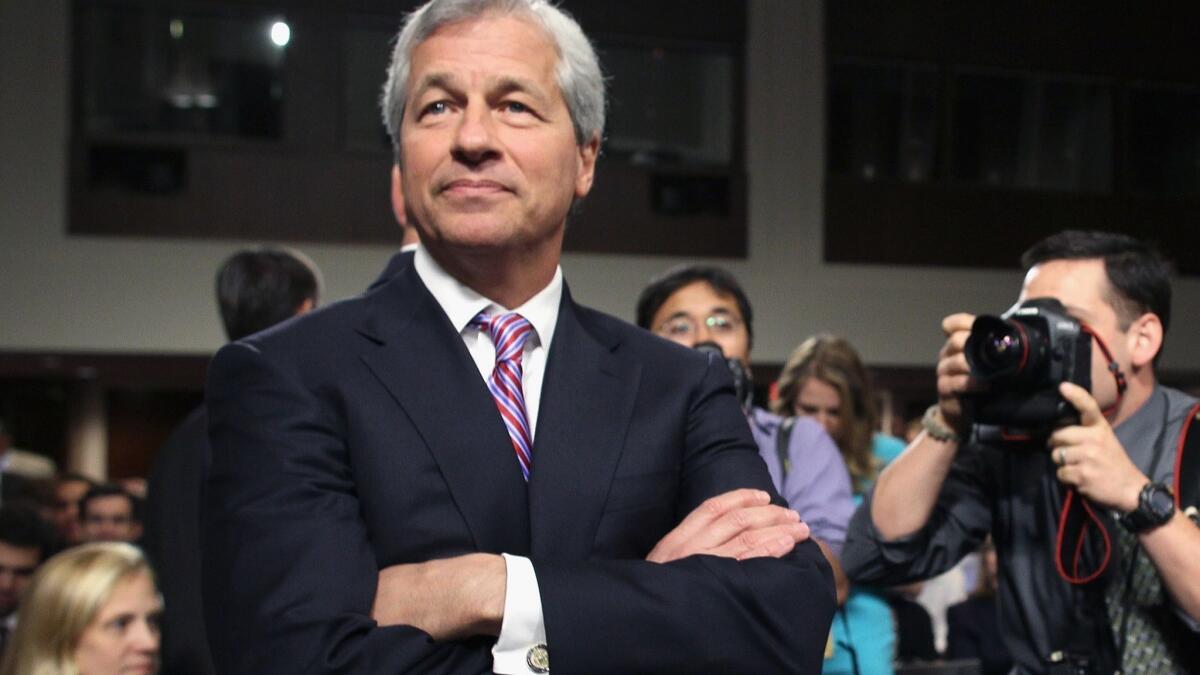

For Jamie Dimon, the lone crisis-era chief executive left on Wall Street, the move hardly looked like the deal of the decade.

But behind his recent bid for a young healthcare payments company called InstaMed is a tectonic shift for JPMorgan Chase & Co. — and the rest of U.S. banking.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, federal regulators have publicly — and often privately — tried to keep giant banks such as JPMorgan, already deemed too big to fail, from getting even bigger. Operating through back channels, Washington snuffed out merger ambitions and discouraged plans to expand businesses, offer new products and open branches.

The goal: to contain the industry, and its worst impulses, without the glare of public scrutiny.

That’s over now. The Trump administration has rolled back the stealth campaign. And the implications — for the banks, their customers, investors and the economy — could be enormous.

Interviews with more than two dozen current and former industry executives and regulators underscore how banks have managed to wriggle free from much of the strict oversight enacted to prevent another meltdown — all without any wholesale changes to the laws enacted on Wall Street after the crisis.

Behind the scenes, the industry’s primary regulators — the Federal Reserve and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency — have adopted a friendlier approach, giving banks more leeway to expand into new markets, introduce products and make acquisitions.

The lighter touch has unleashed bankers’ animal spirits. Deal-making and boom-time arms races are back — as witnessed by a burst of expansion plans such as JPMorgan’s push into new states and its InstaMed Inc. takeover, the bank’s biggest purchase since the financial crisis.

Much of how regulators such as the Fed and OCC interact with banks is confidential. It’s illegal to divulge supervisory information about specific banks because bad news might panic customers. But people with knowledge of the matter described the growth restrictions as one of the more extreme ways regulators during President Obama’s term exerted their control behind the scenes.

Some argue that what seems like a policy shift now is partly just a reflection of the banks’ improved health, which makes their case for growth easier to approve.

The numbers tell at least part of the tale. Banks announced more mergers and acquisitions in the first five months of this year than they did during any full-year period in the last decade, according to data from S&P Global. BB&T Corp.’s $28-billion tie-up with SunTrust Banks Inc., announced in February, was the biggest banking combination proposed since the 2008 financial crisis. Four days after that announcement, Morgan Stanley unveiled its largest acquisition in a decade: a $900-million deal to expand the firm’s wealth business. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. followed suit three months later with its biggest acquisition in almost 20 years.

Banks are also being allowed to expand their reach into everyday America. After years of shutting branches to cut costs, four of the six biggest banks — JPMorgan, Bank of America Corp., U.S. Bancorp and PNC Financial Services Group Inc. — have indicated they’re looking to push into new markets, in some cases for the first time since before the Great Recession.

The timing isn’t a coincidence. Many of the deals wouldn’t have been possible before Trump because the top banking agencies under Obama followed an informal policy to stop or discourage dozens of banks from expanding while they dealt with compliance issues, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

That era’s shadow constraints most often stemmed from compliance issues related to consumer-protection and anti-money-laundering rules, rather than concerns about financial stability, the people said, asking not to be identified discussing confidential information.

The anti-expansionary attitude meant growth plans were derailed even in some situations where the Fed and OCC didn’t usually have formal approval powers, such as when a financial holding company buys non-bank assets, according to people familiar with conversations between banks and their supervisors.

Representatives for most of the banks declined to comment, although spokesmen for SunTrust and BB&T said the two companies are “fully engaged” with regulators in the review process for their merger, and encouraged by “positive comments” they’ve received.

The OCC declined to comment for this story, and a Fed spokesman said the agency’s criteria for reviewing mergers and new branches and markets are clear and publicly available. “While those criteria have not substantively changed in recent years, the financial conditions and risk-management capabilities of many firms have improved and are taken into consideration,” the spokesman, Eric Kollig, said.

Last year, in one of the first signs of a reversal, Trump-appointed regulators green-lighted JPMorgan’s plans to open branches in new states as part of an ambitious national expansion. For years leading up to that about-face, regulators had used their discretion to stifle the bank’s growth.

To be sure, the increase in activity is still a far cry from the spree of mergers in the 1990s that led to the formation of global titans such as Citigroup Inc. and Bank of America.

But the shift is dramatic compared with the first years after the financial crisis. Around 2012, for instance, JPMorgan attempted to set up banking operations in Ghana and Kenya as part of a push to foster more lucrative relationships with governments and multinationals. The plans were derailed when Tom Curry, then-comptroller of the currency, said the move would be too risky, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

Later, JPMorgan executives mapped out a strategy to boost revenue by opening branches in new markets such as Washington, D.C., where the biggest U.S. bank already offered credit cards and mortgages. The OCC told the bank that plan also carried too many risks, the people said. The bank was also quietly prohibited from engaging in mergers and acquisitions, one of the people said.

Joe Evangelisti, a JPMorgan spokesman, declined to comment.

The OCC and Fed almost never use official channels to block a bank’s attempt to engage in new activities such as buying a rival or opening branches. Of the 12,869 proposals banks submitted for Fed approval from 2009 to 2018, the agency denied only two — one in 2013 and another in 2014, according to regulatory data.

Instead, during the Obama years, watchdogs thwarted growth plans before banks had taken formal actions to seek approval, people with knowledge of the matter say.

Bank of America was discouraged from growing while the company worked to resolve a series of private notices, known as matters requiring attention, and public enforcement actions that identified weaknesses across the bank, according to two people with knowledge of the matter. In one example, regulators criticized the way the bank logged and kept track of customer complaints, and it took the company years to resolve the matter. The lender said last year it planned to open 500 new branches across the U.S., including moving into new cities.

“We’ve steadily opened more than 300 financial centers during the last decade, and plan to open over 300 more during the next few years,” said Bill Halldin, a Bank of America spokesman.

At Regions Financial Corp., supervisors stopped the bank from growing in the years following the financial crisis after an internal audit revealed shoddy loan practices, according to two people familiar with the matter. Although the punishment was private, the effect was stark: The bank didn’t open a single branch from mid-2012 to March 2015, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data.

In December 2015, Regions got into trouble for failing to meet Community Reinvestment Act requirements, which led regulators to restrict its ability to do mergers and acquisitions and open branches until it improved its rating. Regions has moved on, opening about 50 branches in the last year and a half. In February, the bank unveiled a three-year plan to boost growth.

Evelyn Mitchell, a Regions spokeswoman, said the bank doesn’t comment on supervisory relationships.

Then there was U.S. Bancorp, which had to put a strategy revamp on hold after the OCC slapped it with a consent order in 2015 for improperly handling suspicious transactions under anti-money-laundering and bank-secrecy regulations, according to a person with knowledge of the matter. It hasn’t opened a branch since 2015, according to FDIC data.

The Minneapolis bank alluded to the restrictions in a February regulatory filing: The termination of the consent order late last year “will give the company more flexibility to optimize its existing branch network and to selectively expand into new markets,” the bank said.

During their tenures, the message from Curry at the OCC and Dan Tarullo, the Fed’s bank-supervision chief, was clear: Compliance should be a top priority and anything that might distract management — such as a planned shift in corporate strategy — was to be avoided.

But three months after Trump’s 2017 inauguration, a sequence of events laid the groundwork for deals to finally get done: Tarullo, whom bankers had nicknamed the “the Wizard of Oz” for his behind-the-curtains influence, stepped down from his post at the Fed. Curry left the OCC a month later, and Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin named a banking lawyer, Keith Noreika, to temporarily replace him. Under Noreika, who ran the OCC for about seven months until November 2017, the regulator relaxed its stance on expansion.

Now unfettered, Dimon is on the prowl. Although he has frequently said he prefers internal growth over deals, he doubts regulators would stand in his way if he tried to expand JPMorgan, according to a person familiar with his thinking.

The 63-year-old chief executive told a recent New York conference that he’s hunting for the bank’s next acquisition, said a person who was in the audience. “I want to do one more big one before I’m done,” Dimon said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.