San Pedro project illustrates a cause of limited housing affordability

- Share via

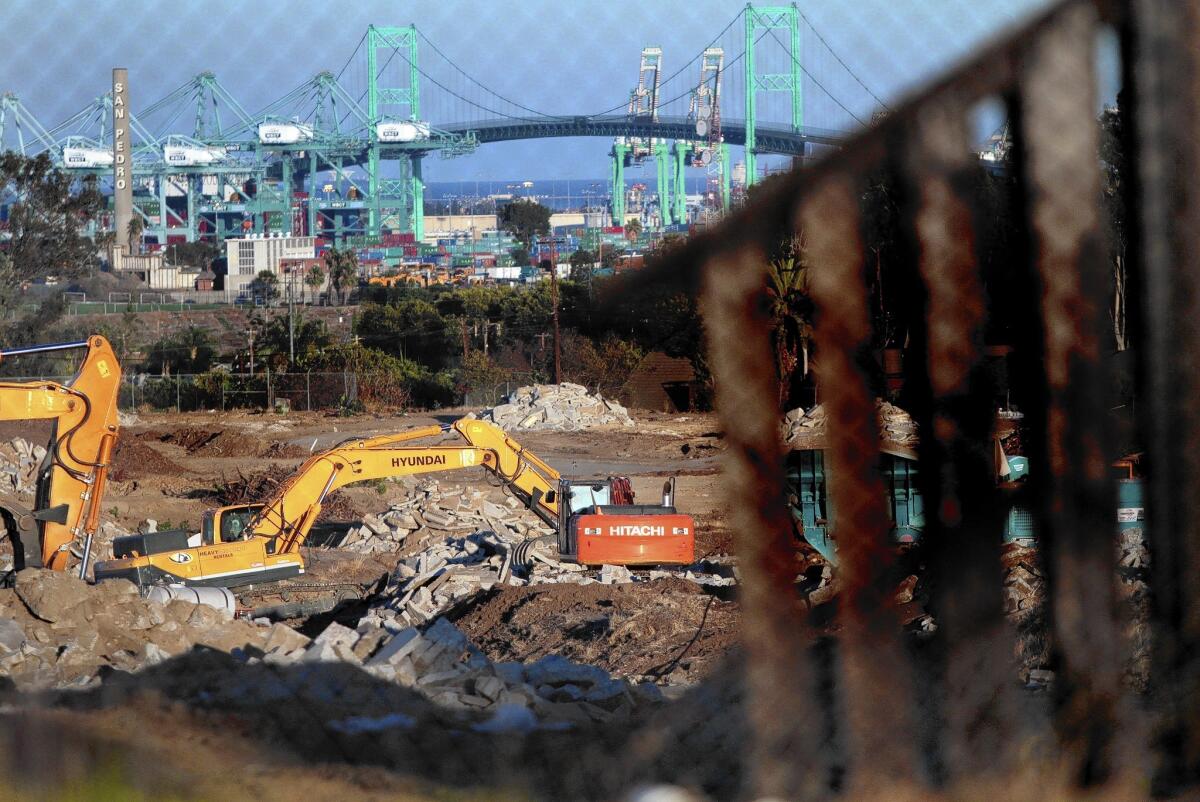

At a groundbreaking ceremony in May, neighborhood activists and local government officials celebrated Ponte Vista, a development of 676 homes in San Pedro.

A white-robed Roman Catholic priest thanked God for the “gift of Ponte Vista,” a welcome addition to a community starved for housing options.

But officials also spoke of the decade it took to get construction started, amid neighborhood protests over the size and style of the homes and the traffic they would bring. Original plans called for a multifamily development with three times as many homes, with many more affordable options.

Now, with plans modified to include 208 single-family homes, prices will range from about $400,000 to $1.1 million.

The Los Angeles project highlights what economists and housing experts call a major contributor to Southern California’s housing affordability problems: Developments routinely get delayed, scaled back or killed amid strong opposition from community groups.

The phenomenon cuts back the supply of new homes and drives up prices, said Christopher Thornberg, founding partner at research and consulting firm Beacon Economics.

“The problem is every single major development goes through that same process: from 800 to 400; from 600 to 300,” he said. The high cost of housing is “a supply issue — period.”

Neighborhood opposition is among several factors constraining home construction. There’s little vacant land left for developers in desirable areas. And many builders, along with their investors and lenders, remain wary of risk after the housing crash.

About 19,000 new homes will be sold this year in the six-county region — 53% less than the 25-year average, predicts Pete Reeb, an economist with John Burns Real Estate Consulting in Irvine.

The difficulty in winning construction approvals, however, is a trend that long predates the housing meltdown and will probably continue long after. California has failed to build enough homes, relative to population growth, every year since 1989, according to a November 2013 report from a state Senate committee.

In Los Angeles and elsewhere, large-scale plans often need special approvals that give neighborhood groups a venue to push back against development. Little land has been zoned for high-density housing. And much of the region has been set aside for the single-family homes that many Southern Californians prefer.

“It’s sort of the desire to keep L.A. a certain way — that is not compatible with it being affordable,” said Richard Green, director of USC’s Lusk Center for Real Estate. “You can have sprawl or you can have density or you can have very expensive housing.”

It will take “many years” of brisk construction — at a much faster pace than California has seen for decades — to make housing significantly more affordable, said Jed Kolko, chief economist of real estate firm Trulia.

But as the Ponte Vista development shows, such a pace would be difficult to maintain.

In 2005, developer Bob Bisno bought the 62-acre site off Western Avenue in northwest San Pedro, seeking to build 2,300 condominiums and town houses and 10,000 square feet of retail space on a long-closed Naval housing complex.

The high density meant many homes would be relatively affordable — giving teachers, firefighters and others a path to homeownership, said Steven Afriat, Bisno’s lobbyist on the project. Many residences also would have been reserved for seniors.

“It was an incredible opportunity for people,” Afriat said.

But because the land was zoned for single-family housing, Bisno needed government approval to build.

To get a zoning exemption, developers must get local government approval after public hearings that allow residents to weigh in. Longtime residents of San Pedro, such as Laurie Jacobs, say it’s crucial that neighbors have a voice. If they don’t, large, poorly planned projects would overwhelm the community with traffic and overtax public services, Jacobs said.

Developers are primarily concerned with profit, not quality of life for existing residents, she said.

“If they don’t live here; it’s not going to affect them,” the vice president of the Northwest San Pedro Neighborhood Council said.

Bisno, who over the years pitched several controversial projects in the region, initially trimmed Ponte Vista to 1,950 units. But many nearby residents said Ponte Vista was still too dense. It would send too much traffic to already congested Western Avenue, they said. Many lobbied hard to retain the single-family zoning.

Rep. Janice Hahn — who as an L.A. councilwoman represented the area during the dispute — joined the fight for a smaller project.

The city Planning Commission rejected the developer’s revised proposal in 2009. Cuts continued until March, when the Los Angeles City Council finally approved the project at one-third its original size.

Crafting a development acceptable to neighbors and the city, while providing homes to those of more modest means, was challenging, said Steve Magee, an executive vice president with IStar Financial, which took over the development in 2010.

“It’s a tough, tough problem, and it’s not just Ponte Vista,” he said. “It’s all over the city of L.A.”

Community opposition to new-home projects isn’t unique to California, although economists say several factors give neighbors and environmental groups more influence here than elsewhere. Since voters passed Proposition 13 in 1978, limiting revenue from property taxes, local governments have increasingly relied on sales taxes.

That means many local governments view housing developments as a burden on city services — they don’t produce enough tax revenue to pay for the added costs they bring, according to experts and the state Senate committee report.

Also, the landmark California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, gives opponents a powerful weapon to block or delay developments through lawsuits, even after they receive planning approvals. CEQA supporters, however, say the state’s environmental law has led to better-designed projects while saving crucial habitat.

The law is often used by neighborhood groups trying to block urban infill projects, but developments in the region’s undeveloped outskirts have also faced hurdles.

Plans for a massive, 20,000-home community along the last wild river in Southern California — first pitched in the 1990s — have been repeatedly delayed by CEQA litigation filed by environmental groups. They argue the Newhall Ranch project, near suburban Santa Clarita, would harm wildlife and threaten the Santa Clara River.

“It’s a very poor way to develop, because you just chew up land,” said Ron Bottorff, a spokesman for Friends of the Santa Clara River, one of several environmental groups involved in the lawsuits. “It’s just typical Los Angeles sprawl.”

Instead, new housing should be directed toward more urban, established cities, he said.

But recent efforts to do just that have faced hurdles as well. Los Angeles, for example, is looking to encourage housing along transit corridors and train stations. City officials say it’s an opportunity to build needed housing while preserving single-family neighborhoods tucked behind major boulevards.

A significant step in those efforts was a zoning plan approved in 2012 that allowed for denser, taller buildings in some parts of Hollywood.

But some residents said the plan would “Manhattanize” Hollywood — choking streets and public services, while robbing views from, and of, the Hollywood Hills.

In February, a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge struck down what he labeled “a fatally flawed” plan, after community groups sued under CEQA to stop the new rules.

Agreeing with those groups, Judge Allan J. Goodman said the city relied on flawed projections of population growth in Hollywood and that officials didn’t properly study alternatives, such as reducing density in the neighborhood.

No one would mistake the new Ponte Vista for Manhattan. The project’s suburban character — with many single-family homes, in addition to condos and town homes — represents a stark contrast to the original proposal. Some of the larger single-family homes, perched on a hill, will have views of the Port of Los Angeles.

Where the developer once proposed an apartment building, there will be a 2.4-acre park, for both residents and the public.

Los Angeles City Councilman Joe Buscaino, who now represents San Pedro, called Bisno’s original proposal “too much.”

But he noted some opponents wanted only single-family houses on the site, which would have meant fewer homes at higher prices. The ongoing debate, he said, left the land blighted and devoid of new housing for years.

“There is a housing shortage in the city of L.A.,” he said. “Either you are going to have an uproar in the community and not build anything, or move forward and get something done.”

Times staff writer Sandra Poindexter contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.