- Share via

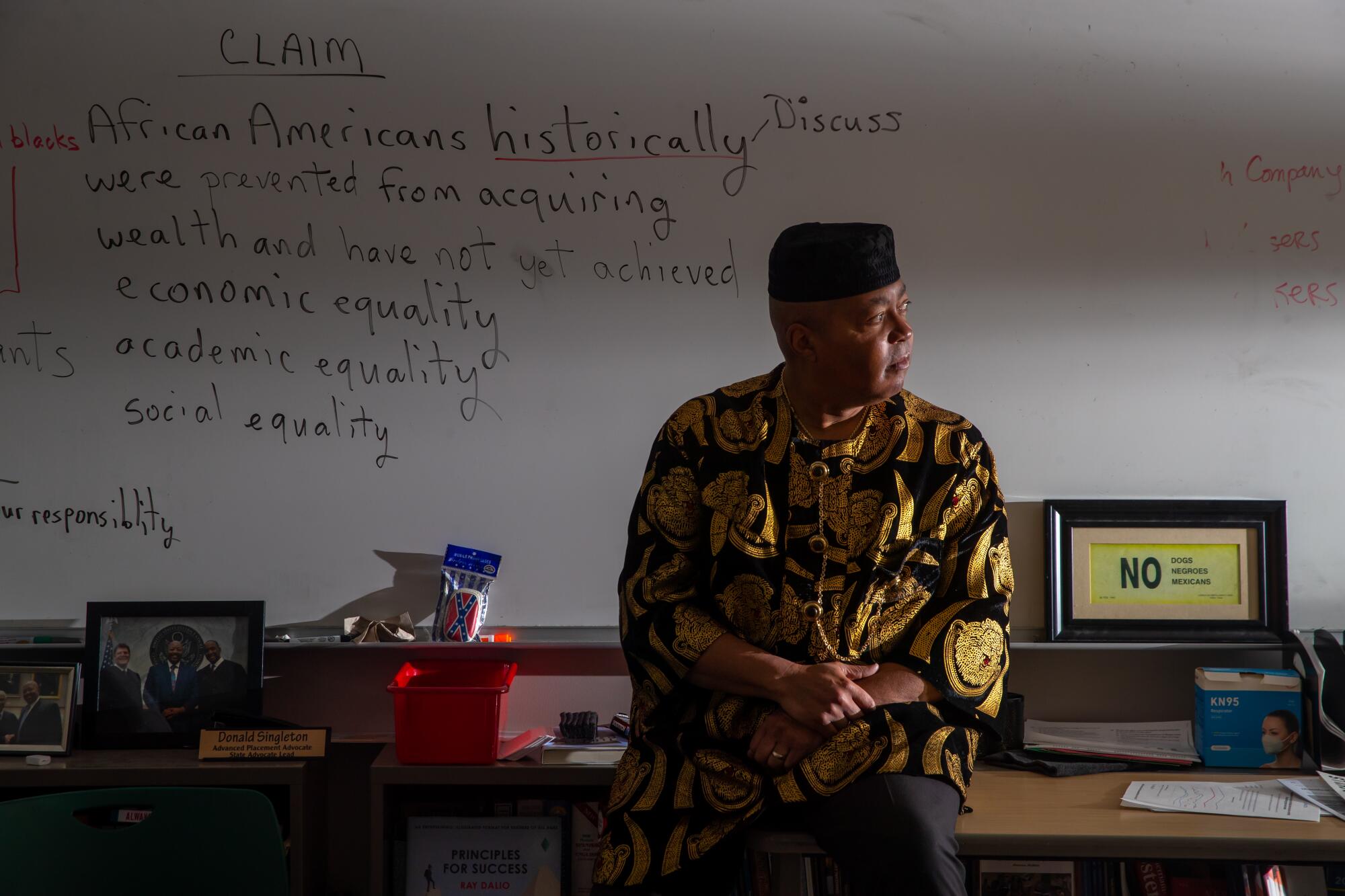

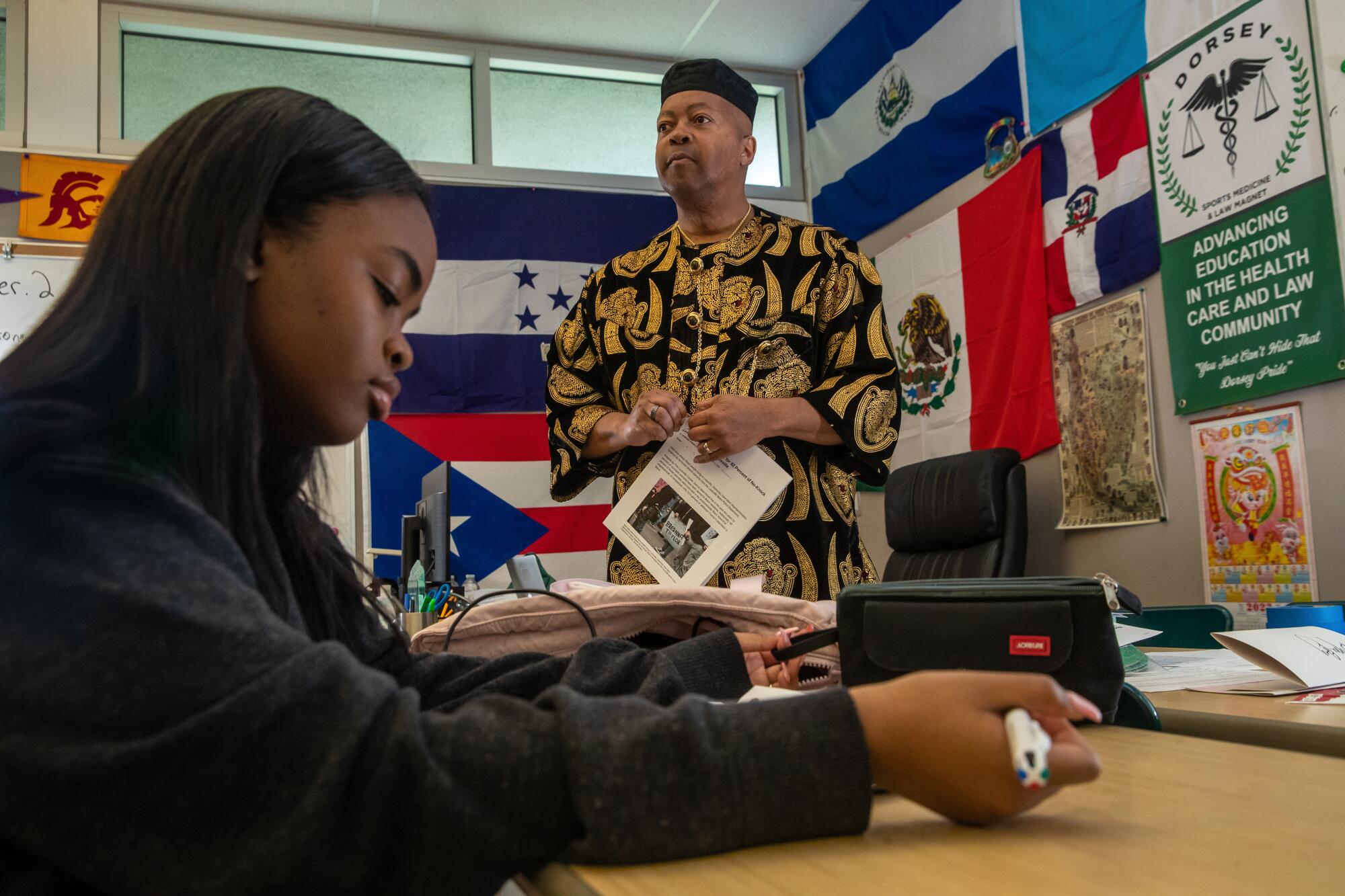

Inside a Dorsey High School classroom — decorated with African flags, dolls in colorful African clothing and a wall of fame that included pictures of Thurgood Marshall, Wilma Rudolph and Colin Powell — social studies teacher Donald Singleton and 18 students waded into the nation’s debate over Black history and race.

“Who thinks that right now, in 2023, there is discrimination against Black people?” Singleton asked. “Everyone’s created equal. How can there possibly still be discrimination? We’re now in 2023?”

Laylah Cooper, a senior, dived in: “Racist mind-sets are passed down from the family.”

“We had a Black president,” Singleton continued. “We have a Black vice president. Why isn’t racism dead?”

“White people never viewed us as people,” said Allegresse Ngoma, a junior, drawing on earlier discussions and readings. “Like we were compared to animals and we were seen as property. In their eyes we will never be equals” even though “we just want to be given the same opportunities as everyone else.”

For nine months these students in South L.A. were pioneers in one of only 60 classrooms nationwide, and the only one in the L.A. Unified School District, taking on College Board’s new Advanced Placement African American Studies class. The pages of their syllabus became an entry in the nation’s culture wars as this teacher and his students — all Black or multi-race Black — engaged in discussions that in many states could be against the law.

Thirty-six states have restricted education on racism, bias or the contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups to U.S. history. One of those is Florida, which under Gov. Ron DeSantis has outright banned the new AP class, saying it “lacked education value” and was “woke indoctrination.”

The dispute over Florida’s overall educational approach to African American studies re-erupted last week, when the state approved new learning goals for African American history. Critics, including Vice President Kamala Harris, focused on a learning standard that includes “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Meanwhile, California is one of 17 states — including Washington and Delaware — that has expanded education on racism, bias and the contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups to U.S. history.

College Board, the organization that created and oversees the Advanced Placement program, has been criticized by Black studies scholars and others for appeasing some conservatives by watering down or eliminating topics from the core materials of the new AP class, such as reparations, Black Lives Matter and Black queer studies.

All along, the course has been rooted in the past and the revised curriculum makes it more so.

In the updated framework for next fall, the course begins, as before, by examining the diversity and complexity of African societies and their global connections prior to transatlantic slavery. Course goals also include evaluating concepts and events that shaped Black experiences in America.

About eight weeks will be spent on “Freedom, Enslavement and Resistance”; five weeks on “The Practice of Freedom”; seven weeks on “Movements and Debates.”

Teachers are free to add related topics to their classes, but students will be tested only on College Board-approved curriculum. Student research papers, which are required as part of the AP test, can tackle any topic related to African American studies.

Singleton remained within the core materials when he covered lynching, housing and job discrimination, the impetus for race riots, art and cultural contributions. But next year he’ll be stepping outside the core framework, for example, if he continues to teach about potential cash reparations for Black citizens. In California this issue is part of a groundbreaking effort to redress harms from slavery and discrimination.

Over the year, his students were introduced to Black authors in the core materials, including W.E.B. Du Bois — the first African American to earn a doctorate at Harvard — who spoke against unfettered capitalism and dared in the early 1900s to demand full political empowerment for Black people. And Frantz Fanon, who in the early and mid-20th century witnessed and opposed colonialism as an author, doctor and revolutionary from the front lines of Martinique, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia.

“What’s happening today is relevant to what happened in the past,” said Quran Turner, a junior. “Going back in history, it helps me see how I can move forward, what I can do.”

The teacher

Singleton, 62, has a law degree, National Board certification as an instructor and 30 years of classroom experience. He leads the school’s mock trial program and formerly coached the school’s Academic Decathlon team. It was not happenstance that he was entrusted with this class. He has a long history with College Board — as an AP teacher, exam-grading leader and ambassador for the AP program.

“I love talking about the government and what it can or cannot do,” he said.

He’ll often give his government students an official U.S. citizenship test at the start of the year. “After it’s over, I say, ‘You know what? All of you would be getting deported. You know nothing about this country.’”

He’s patient with teenage struggles — especially in the wake of the pandemic — trying to overlook absences while also cajoling and admonishing students on the importance of showing up. He reluctantly flunked one bright student in the class who did not show up enough.

For many students his room serves as a sanctuary where they hang out between classes — helping with classroom chores, doing homework, reading — where being smart and trying hard are celebrated.

Singleton noted that his students have supported him, too, encouraging him to keep going when his son died unexpectedly from a seizure in 2022 at the age of 37.

For Singleton, this AP class offered something new, an opportunity for maturing teenagers to learn in depth about African origins and what it has meant to be Black in America, an opportunity that “99% of my young people don’t get.”

“Everyone should know that African American history did not begin with the denigration of slavery, but in the continent of Africa — replete with leaders and business people, entrepreneurs and military geniuses,” he said.

Singleton wishes he had white students in the class, but virtually no white students attend Dorsey, which is about half Black and half Latino.

His class was by no means an extended Black History Month. He cultivated developing scholars who learned deeply about the beauty of African culture, but especially about injustices and violence perpetrated upon Black people over more than 400 years in America — and how that history relates to the current circumstances.

Course goals also included learning strategies that African American communities have used to represent themselves “authentically,” promote advancement and combat inequality — including political advocacy, education, migration, litigation and direct action — taking in violent responses such as slave revolts as well as the peaceful sit-ins of the 1960s civil rights movement.

Materials also encompassed cultural milestones represented in the literary, artistic and intellectual flourishing of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s.

Singleton did not espouse a sense of hopelessness or grievance, aiming instead for intellectual clarity on the wrongs and sufferings of the past to help students develop racial pride, activate self-reliance and civic involvement while navigating a world where individuals still encounter racism.

And he doesn’t want anyone to hate anyone else.

“I teach love,” he said. “Sometimes, some white people are really upset when Black people say they love themselves because, to these white people, it may mean hatred for white people. But that’s not true.”

The course

AP classes are designed as college-level courses for high school students, who can earn college credit by passing standardized tests in subjects that include calculus, biology, physics and English language and composition. Students also take these classes to strengthen college applications.

Part of Singleton’s role is to provide feedback to College Board as it continues to shape the course. He’d suggested more emphasis on the Black diaspora to the Americas beyond the United States. In the fall, the pilot will expand to 800 schools and 16,000 students. This coming year, for the first time, students can earn potential college credit by taking the AP exam for this course. In 2024-25, all schools will be able to offer the course. The course, however, will probably be discontinued in Florida, a College Board spokeswoman said.

Florida officials said last year’s pilot version of the course violated state laws. The state objected, for example, to the inclusion of writers who criticized capitalism, such as bell hooks, and topics that included reparations without “balancing opinion” against reparations. College Board has not submitted all the materials necessary for Florida to reconsider the revised curriculum, said Cassie Palelis, deputy director of communications for the Florida Department of Education.

Teachers elsewhere also face potential repercussions for how they teach about racial issues — especially as contemporary topics almost inevitably veer into politics.

South Carolina, for example, has banned any instruction that suggests a member of one race could “bear responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex” as well as teaching that could make an individual “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his race or sex.”

This spring, local officials in that state shut down classroom discussion drawing from Ta-Nehisi Coates’ award-winning memoir “Between the World and Me,” which discusses the ongoing effects of racism in the form of a memoir from the author to his son. One student had complained in writing to local officials of being “incredibly uncomfortable,” adding, “I am pretty sure a teacher talking about systemic racism is illegal in South Carolina.”

In Los Angeles, schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho enthusiastically affirmed Singleton’s class.

“In contrast to what we’ve seen in other places, I think we are on the light side of these issues, not the dark side,” said Carvalho, who served as superintendent in Miami before coming to L.A. “I rejoice over the fact that we can celebrate African American history, African history, the civil rights movement. The more recent historical tragedies that have inspired movements — those should not be ignored. They should be acknowledged, studied and understood.”

Inside the classroom

On a Thursday in April, Singleton introduced students to the writings of Fanon, a psychiatrist whose work remains part of official course materials. His writings explored the racism and violence inherent in colonialism. Like many Black writers, he pushed back against capitalism — it was, in their experience, a system that freely incorporated racism. Fanon also helped embed into Black activism the concept of “by any means necessary,” a credo of civil rights leader Malcolm X.

Before taking the class, most of the students were barely familiar with Malcolm X, let alone his intellectual precursors. Singleton noted that it was not until college that he’d had an opportunity to learn of Fanon, who witnessed European colonialism firsthand.

M’Kayla Weatherspoon, a senior, spoke of what she saw as the long-term effects of colonialism on Black aspirations.

“We try to take basically what was given to us instead of actually going and doing what the white man can do,” she said.

Holland Cooper, a senior, segued to the effects on health issues among Black residents in her neighborhood.

“Wait,” interjected Singleton. “Isn’t that your fault? That you are unhealthy, that you’re obese, you have high blood pressure, diabetes. I mean, you can’t blame that on somebody else. Can you?”

“That’s all we know,” Holland said. “We have all these fast-food places on every block. So that’s all we have to eat. We don’t really have supermarkets in our neighborhoods. We have to drive far out to get healthy food.”

Jailynn Butler-Thomas, a junior, shifted the discussion to environmental racism. A factory will be built close to a Black neighborhood, she said, “even though the chemicals can cause cancer or cause the water to be poor ... and it causes a bunch of health problems that no one really speaks about.”

One classroom conversation evolved into how Martin Luther King Jr. has long been a more comfortable figure for mainstream America than Malcolm X because the latter is “more ‘Get it done by any means’ — if necessary by killing or fighting or anything,” said Quran. “Dr. King was a lot more peaceful.” Authorities “want people to be peaceful ... like little sheep.”

Gianna Reynolds, a senior, spoke about “by any means necessary” in terms of the 2nd Amendment, which talks of the right to bear arms, an act of self-protection that mainstream America perceived as dangerous, she said, when the Black Panthers exercised that right by arming themselves in the 1960s.

“The 2nd Amendment, the right to bear arms, is more accepted when Black people are using the arms on each other rather than on their oppressors,” Gianna said. “When Black people use violence to fight back against the things that we’re suffering through, it’s seen as savage, but when white people did it initially to gain their independence from Britain, they were seen as patriots and heroes.”

Such discussions were intensely personal for these students, who frequently said “we” when talking about past victims of oppression. But the talks were far from expressions of hopelessness.

“We can get out of it if we try and use our brains because we’re all smart in this class.... And we all could make it to college and past that,” said junior Bry’anna Bennett.

Singleton doesn’t necessarily agree with all the views of his students.

Jailynn, for example, has become an activist calling for the elimination of school police. Singleton said he finds the school police to be respectful and helpful. He made a distinction between them and the police who stood by, in 1925, as a white mob attacked the home of Black doctor Ossian Sweet, who had fearlessly moved into a white Detroit neighborhood — an incident Singleton referenced in class.

What they learned

For their research paper students chose topics that included: the effects of the domestic slave trade on Black families; the influence of African culture on dance, music and lifestyle; the Black middle class in the 20th century; race and healthcare outcomes in the United States; the history of Black resistance.

In interviews, students talked about what they had learned over the year.

When you make a man feel inferior, “you don’t have to worry about him obeying — because of things that you have embedded or put into his mind,” said Allegresse, who spoke no English when she emigrated from Congo nine years ago. She added that the course deepened her understanding of class and cultural divisions within the Black community here and abroad.

“Being in this class,” said Gianna, “showed the history of court cases that have benefited Black people and people of color and how even simple law changes have benefited us in the long run. So if we vote and we continue to push for the changes that we need and believe, our voices do matter.”

Jailynn, who was inspired by African queens, said the class “really helps the way you see yourself.” Also, learning about organizations including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Black Panther Party “taught me a lot about what people power is and the power in coming together as a community. I think a way we are doing that now is through this course.”

In a show of hands, everyone in the class said they were more likely to vote because of what they had learned. Two-thirds plan to attend college. Several are considering a major or minor in Black studies.

Singleton called the experience “the most rewarding class I have ever taught because the information is so empowering. AP African American Studies is transformative because African-descended children finally see themselves reflected in the courses they take. And all other students learn the connection between Africa, which is the birthplace of humanity, and every other culture.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.