- Share via

Book Review

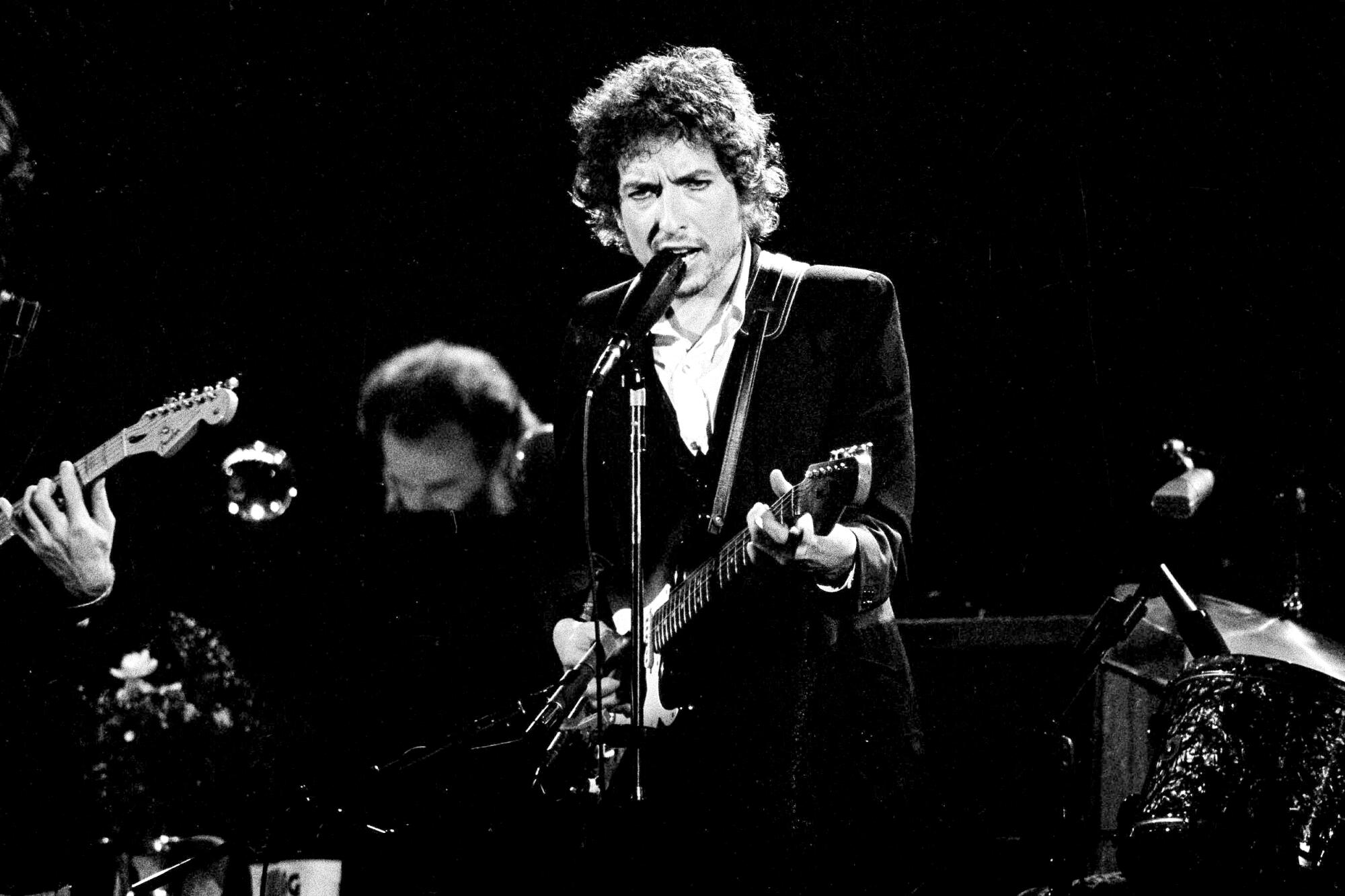

Bob Dylan: Jewish Roots, American Soil

By Harry Freedman

Bloomsbury Continuum: 248 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The word “probably” gets a major workout in “Bob Dylan: Jewish Roots, American Soil,” Harry Freedman’s new book made of equal parts passion and conjecture. The book’s central premise, or one of them, sounds juicy: The man born Robert Zimmerman, and raised by a middle-class Jewish family in small-town Minnesota, worked hard to turn his back on his Jewish roots, adopting an anglicized name and spinning a string of tall tales about his background and upbringing. And yet, as Freedman implies throughout, elements of Dylan’s Jewishness remained central to his art and identity, from his commitment to social justice to his imaginative formation of a new persona.

It’s an intriguing idea, but one that Freedman, billed by his publisher as “Britain’s leading author of popular works of Jewish culture and history,” never really pins down. He does, however, have fun trying. Even as he wanders away from his thesis for pages and pages at a time, Freedman provides a lively gloss on Dylan’s rise from unknown folk beacon to counterculture superstar and, to some, plugged-in traitor to the folk cause. This period, of course, is also the subject of the recent movie “A Complete Unknown,” which was based on Elijah Wald’s superb book “Dylan Goes Electric.” There will never be a shortage of Dylan movies — or books.

So what makes this one worth reading? For one thing, it’s a little strange. Freedman, whose previous books include “Leonard Cohen: The Mystical Roots of Genius,” writes in a sort of modified hipster patter that fits in well with the Beat poets Dylan once idolized, and whom the author cites as another big influence on the young singer-songwriter. The author has a curious relationship with commas; his sentences often run on to the point where you might find yourself looking for periods without finding them. Sentence structure sometimes ends up blowin’ in the wind: “Coming on at midnight to perform just two numbers, the crowd went wild.” Yes, I suppose the crowd would go wild if it went onstage at midnight, or any other time really.

Led by Timothée Chalamet and a superb cast that includes Monica Barbaro and Elle Fanning, director James Mangold’s film captures the cruel side of Bob Dylan.

Devoting generous space to the civil rights movement, the Red Scare, rock ’n’ roll and other sociopolitical foment of the ’50 and ’60s, Freedman can adopt the tone of an earnest YA author: “The kids were looking for fun, at this stage in their lives they weren’t looking to change the world. But change the world they would. There was no colour bar to their love of music.” But he can also surprise with sudden, mischievous wit. On the protesters confronted by police at the Washington Square Park “Beatnik riot” of 1961: “A few sat in the fountain and sang ‘We Shall Not be Moved.’ They were.”

And here he is on the antipathy that Mary Rotolo, mother of the young Dylan’s girlfriend Suze, had for Dylan: “She didn’t have the same maternal feelings towards him as the other older women who had mothered Bob when he first arrived in New York, but that was bound to be so; he wasn’t shtupping their 17-year-old daughters.” “Jewish Roots” has what a book with a shaky premise needs to still be readable: a voice that never really gets dry.

But then there’s the “probably” problem, which represents a larger issue of floating ideas that don’t have the backing of fact. “Bob Dylan was probably in the park that April day in 1961.” And this about manager Albert Grossman: “The fact that both Dylan and Grossman were each blessed with temperamental Jewish volatility would tear their relationship apart in due course. But at this stage their cultural background probably helped to create a chemistry, a shared ambition for success.” This example underscores a separate issue that defines the book. Eager to serve his premise regarding Dylan’s Jewishness, Freedman sometimes turns it into a flimsy fallback device. “Blessed with temperamental Jewish volatility”? Sure. Maybe. Probably? It’s pretty thin stuff, and it’s indicative of an argument that never really coheres.

The two giants of American song performed Friday night as the annual Outlaw Music Festival stopped at the Hollywood Bowl.

In other places, however, Freedman can be quite sharp about the matter. Here he is describing Dylan’s reaction to discovering that his friend and fellow musician Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was also Jewish: “Dylan had discovered he wasn’t alone, and the suspicions of his friends had been confirmed; Bob Dylan was Jewish. And, of course, it didn’t matter a bit. That’s the funny thing about being Jewish. The antisemites hate you, the philosemites want to be like you, and nobody else gives a damn. It’s a lesson that every Jew with a crisis of identity learns eventually. To stop being so self-conscious and accept the reality of who you are.”

Of course, if nobody else gives a damn, one might wonder about the purpose of this book. As it is, “Jewish Roots, American Soil” makes for fun reading even when it doesn’t quite seem to know what dots it wants to connect. This would hardly be the first box that the famously elusive, self-mythologizing Dylan doesn’t quite fit.

Vognar is a freelance culture writer.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.