With ‘Don’t Look Up,’ Adam McKay and Netflix take the comedy of dread mainstream

- Share via

This is the first 2022 edition of the Wide Shot newsletter about the business of entertainment. If this was forwarded to you, sign up here to get it in your inbox.

“Twenty-thousand years of this, seven more to go” — Bo Burnham, “That Funny Feeling” song in “Inside”

“We really did have everything, didn’t we?” — Dr. Randall Mindy, “Don’t Look Up”

During the press tour for the end-of-the-world satire “Don’t Look Up,” writer-director Adam McKay has referenced some obvious hallmarks — “Dr. Strangelove” and “Network” among them — that inspired his skewering of government, media and industry.

I thought of those works while watching the film during the holiday break, of course. But I also recalled a very different type of movie: Stanley Kramer’s “On the Beach.”

Like “Don’t Look Up,” Kramer’s film for United Artists was a mass-market product anchored by high-wattage stars (Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner and Fred Astaire) that dealt with what was considered to be the planet-killing crisis of its time. Released in 1959, “On the Beach” depicts the slow, quiet annihilation of humanity from the nuclear fallout of a third world war.

To use a scholarly term, it’s a real bummer in a way that is reflected in the final act of “Don’t Look Up” as the characters face the fact that the end is nigh. Unlike “Don’t Look Up,” “On the Beach” didn’t go for laughs. It was also not commercially successful, reportedly losing some $700,000 (about $6.7 million in today’s dollars).

But “Don’t Look Up” has done something remarkable, though about half the people discussing it online seem to hate it.

At a time when audiences supposedly crave nothing but escapism, McKay’s film has brought a thinly veiled critique of the climate change discourse into the mainstream. Released Christmas Eve, the star-packed movie racked up 111 million viewing hours in its first three days, according to Netflix. It was the No. 1 movie worldwide on the streaming service.

Critics either love it or loathe it. “Don’t Look Up” has a 56% positive score on Rotten Tomatoes. But its “audience score” — which was once considered unreliable but has become an increasingly potent studio marketing tool — is much higher, at 77%. McKay himself, a vocal social media user, has defended the film on Twitter. Like, he’s retweeting a lot of stuff. For what it’s worth, all my lefty non-Hollywood friends I talked to during the break either had already seen it or wanted to.

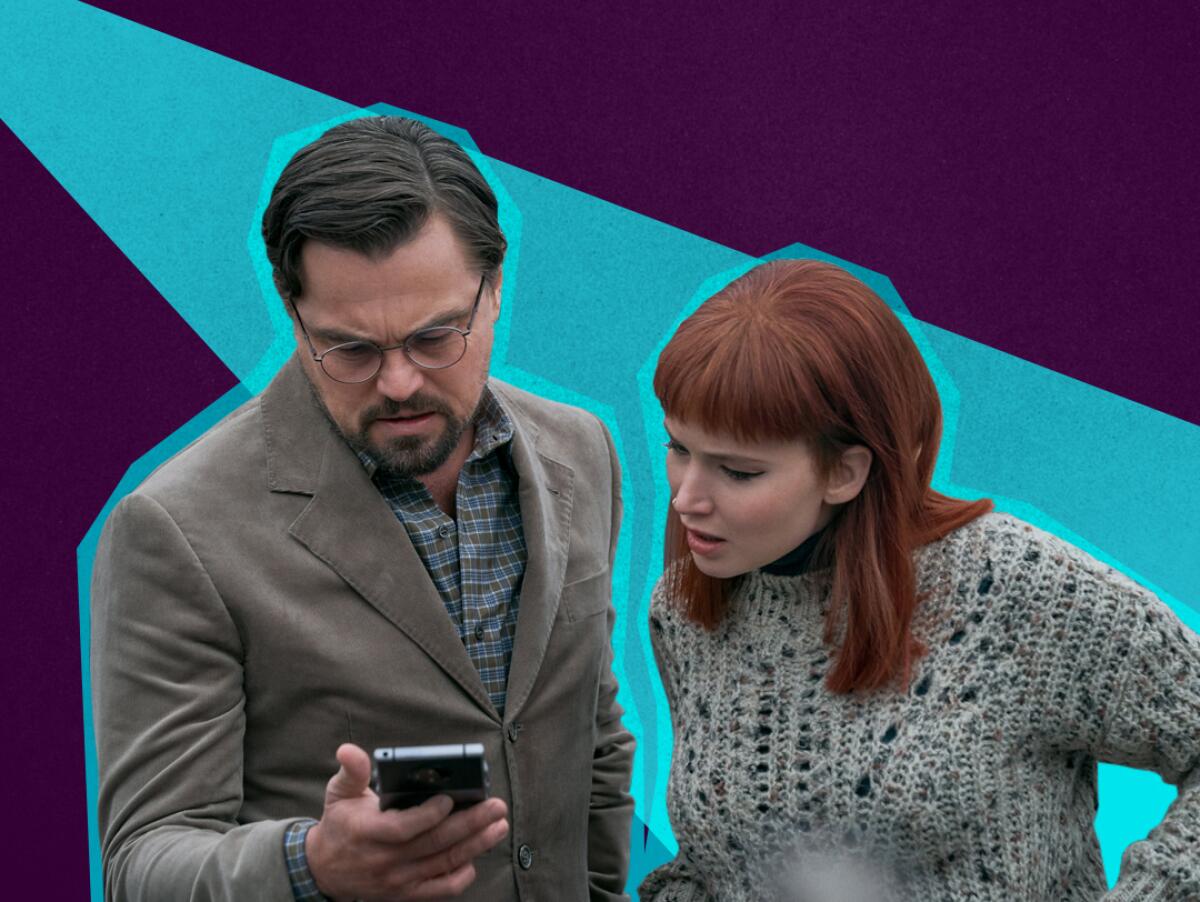

The A-list cast, led by Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence as scientists trying in vain to warn the world of a comet hurtling toward Earth, clearly helped. In last week’s edition of this newsletter, we hinted at the growing influence of star power in streaming while discussing how IP-driven productions have supplanted actors’ ability to draw audiences at the box office.

I first saw “On the Beach” as part of an undergraduate science history class on the atomic age taught at UC Santa Barbara. The film came out 14 years after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and several years before the Cuban Missile Crisis, so the dangers of the bomb were not far from the public’s consciousness at the time.

During the Cold War, the uneasy sensation of living with the possibility of nuclear Armageddon seeped conspicuously into popular culture. Who knows how future historians will look back on cultural industries’ responses to our current moment?

If we tried to design a syllabus for “Film in the Age of Climate Crisis,” it would be pretty thin, especially if the professors had to stick to popular fare rather the soul-turning horror of Paul Schrader’s “First Reformed” or Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth” documentaries. What else goes on the list? “The Day After Tomorrow”? Bong Joon-ho’s “Snowpiercer”?

In a 2019 Variety piece on Hollywood and the problem of our changing atmosphere, no less an environmentalist than James Cameron questioned the effect movies could have.

“Frankly [audiences] don’t want to hear about climate change,” Cameron told the publication. “We did a [documentary] show called ‘Years of Living Dangerously.’ We won an Emmy and got canceled. ... Does [storytelling] do that much good?”

That’s a question the industry is still grappling with.

There’s surely a preaching-to-the-choir aspect to “Don’t Look Up.” But the response to the film shows that there’s at least some appetite for entertainment that directly tackles an issue that, to many, feels intractable. On a much smaller scale, comedian Bo Burnham’s special “Inside” captured Gen Z’s existential dread over various calamities, including climate change, social media and the ongoing pandemic.

One of the complaints against McKay’s film is that its messaging is not exactly subtle. There are seas of red hats at rallies for the president played by Meryl Streep. Mark Rylance’s bizarro tech billionaire attempts to profit from the incoming space object. The toggling of dark comedy and dire warning is a complicated balance to strike.

Plenty of filmmakers have delivered their doomsday messages by playing with clashing tones. Think of Vera Lynn singing “We’ll Meet Again” over mushroom cloud footage in “Dr. Strangelove” or Burnham’s sing-songy “ba-da-da, ba-da-da” outro for “That Funny Feeling”: “Hey, what can you say? We were overdue. But it’ll be over soon.”

Others take license to be more strident. In the closing frames of “On the Beach,” after the world has finally succumbed to global radioactive doom, Kramer cuts in on a shot of a banner reading “There is still time .. brother” set to a screeching orchestral score. Yeah, it’s not subtle. I still find it chilling. “Don’t Look Up” also goes for a gut-punch.

For all its reputation for liberal grandstanding, Hollywood is still trying to figure out how to use its commercial art to convey anxiety about melting glaciers, rising sea levels and burning forests. If nothing else, “Don’t Look Up” could break the ice, so to speak.

Stuff you should read

Some links may require a subscription.

— Farewell, Bob Iger. Disney’s Bob Chapek era starts now. As the Mouse House moves forward without its visionary leader, Chapek must refire the creative engines to grow Disney+. (LAT)

— 10 years after the end of her iconic show, Oprah Winfrey still best embodies TV today, writes Washington Post television critic Inkoo Kang. (WaPo)

— Hollywood weighs new production safety measures as Omicron surge hits West Coast. An alliance of Hollywood studios and entertainment industry unions are considering potential changes to current COVID-19 safety protocols for film sets. (LAT)

— Streaming wars drive media groups to spend more than $100 billion on new content. Investment outlays come amid concerns that it will be harder to attract new viewers in 2022. (Financial Times)

— Green light! Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is set to receive $40 million in compensation this year. That’s a lot, but it’s also about what he got in 2020. (Variety)

— What made Betty White the most beloved TV star of her (or maybe any) generation. TV critic Robert Lloyd pays tribute to late Golden Girl. (LAT)

Number of the week

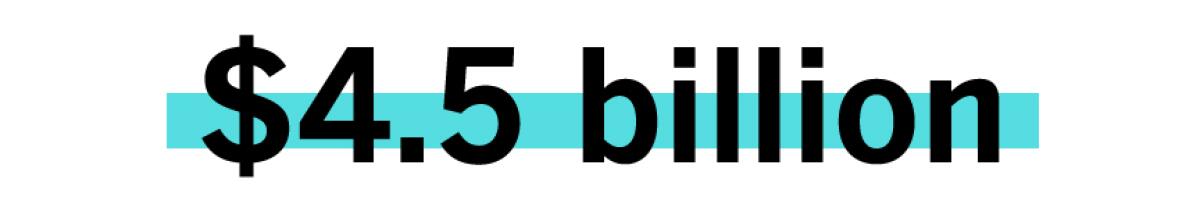

The U.S.-Canada box office ended 2021 with $4.5 billion, according to Comscore, down 60% from the pre-pandemic year of 2019, when movies grossed $11.4 billion domestically. Hey, it’s better than 2020, but what isn’t?

Sure, the full-year numbers tell only part of the story. The National Assn. of Theatre Owners points out that from July to year-end, ticket sales were off by 40% compared with the same period in 2019. That’s still not great, but it shows a clear improvement in the last half of the year as more movies came out and vaccination rates improved.

Yet it could be a long time before the annual North American box office clears the $10-billion milestone again. Most theater owners, distributors and analysts doubt it will reach that benchmark in 2022. Maybe 2023?

Next year’s movie lineup features some big swings from Hollywood, including “Top Gun: Maverick,” “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” and “Avatar 2.” The big box office totals that once cheered exhibitors have always depended on the blockbusters.

But “depth” in the market is important too, and a lot of the movies that would’ve padded the numbers in between the tent poles — those rom-coms and adult dramas that we keep droning on about here — are now going straight to streaming or getting truncated theatrical releases.

How much of a permanent dent will that put in the market? Bloomberg Intelligence senior media analyst Geetha Ranganathan said in a Monday report that shortened theatrical windows could cut domestic box-office sales by as much as 10%. We probably won’t find out until a couple years from now.

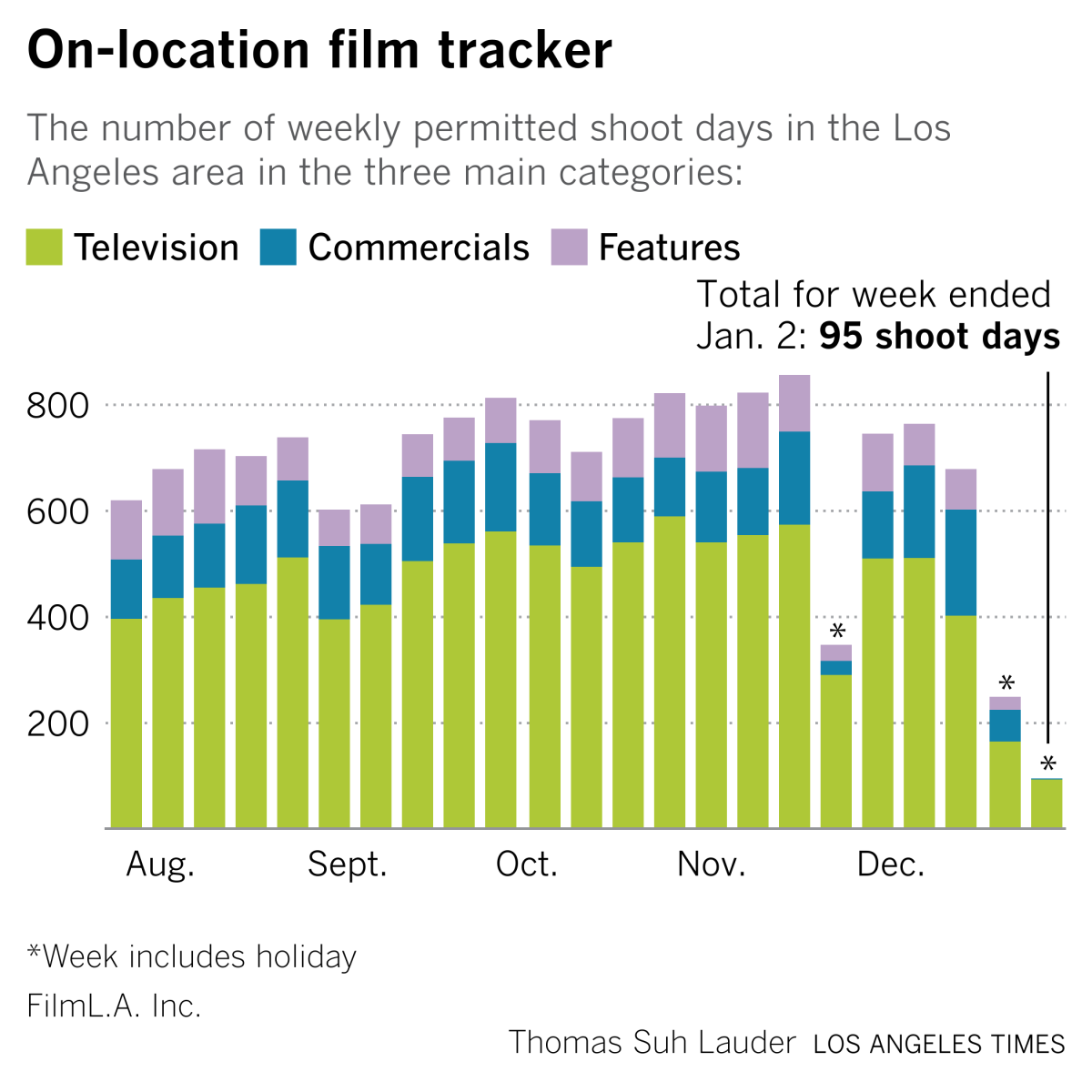

Hollywood production

Productions are typically slow during the holiday period, and that was certainly the case this year. Productions in the Los Angeles area totaled 95 shoot days for the week that ended Jan. 2, including 93 days for television, two for commercials and none for features, according to FilmLA data.

Some good news

SPAGHETTI IS BACK, PEOPLE. I repeat, spaghetti is back.

Forget “Spider-Man.” The marquee getting folks excited in Los Angeles’ Frogtown neighborhood was the sign at Rick’s Drive In & Out announcing the return of the noodly dish to the old-school Dodger-themed diner’s menu.

Times writer Stephanie Breijo deliciously chronicled the origin of the unintentionally hilarious sign, which has had an viral moment since its unveiling. Seriously, where did spaghetti go, and who can we blame?

Breijo also reviews the famous dish (it’s fine).

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.