- Share via

SAN DIEGO — Robert Garant proudly showed off a collection of chain saws he’s used to maintain the nearly 2 acres he and his wife, Gladys, have lived on for 47 years in San Diego County’s bucolic mountain hamlet of Julian.

The retired school bus driver said pruning the oak trees and dense shrubbery around their home isn’t just an aesthetic endeavor. Maintaining what’s commonly known as defensible space, he explained, can be a matter of life and death.

“We actually saved our house by clearing that whole perimeter,” said Garant, recalling the ferocious Cedar fire in 2003 that burned down over 2,800 buildings but spared their home. “The only thing I lost was a hose.”

For many rural and suburban Californians, the approach of hotter, longer days is tinged with trauma and a persistent fear.

With a tinder-dry summer on the horizon, Gov. Gavin Newsom has released an unprecedented $1-billion blueprint for wildfire prevention, making a deal with legislators in early April to fast-track more than half of the money.

The governor’s plan calls for clearing vegetation on half a million acres a year, up from the current annual pace of about 80,000 acres. The approach stems largely from anxiety over drought and invasive beetles, which killed nearly 150 million trees last decade in the Sierra Nevada.

However, a growing chorus of wildfire experts and environmental groups say Newsom’s plan shortchanges homeowners like the Garants — prioritizing logging and other projects ill-suited to stop the type of wind-driven blazes that have repeatedly devastated communities across the state.

That’s especially true, researchers say, in Southern California, where wildfires predominantly burn though chaparral and grasslands, blasting communities with ember storms, such as in the 2007 Harris fire in San Diego County, the 2017 Thomas fire in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties and the 2018 Woolsey fire in Ventura and Los Angeles counties. But it also applies to the recent spate of blazes that have plagued northern parts of the state, including the Tubbs, Nuns and Camp fires.

“There is a pretty big disconnect between this budget and trying to do something about the loss of lives and homes,” said Max Moritz, a widely recognized wildfire expert with the University of California Cooperative Extension in Santa Barbara. “Those forest treatments, they don’t do barely anything to alleviate the risk to human communities.”

Newsom’s team was quick to point out that, while the state spends billions on wildfire suppression, largely through the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, it has never dedicated such resources to prevention.

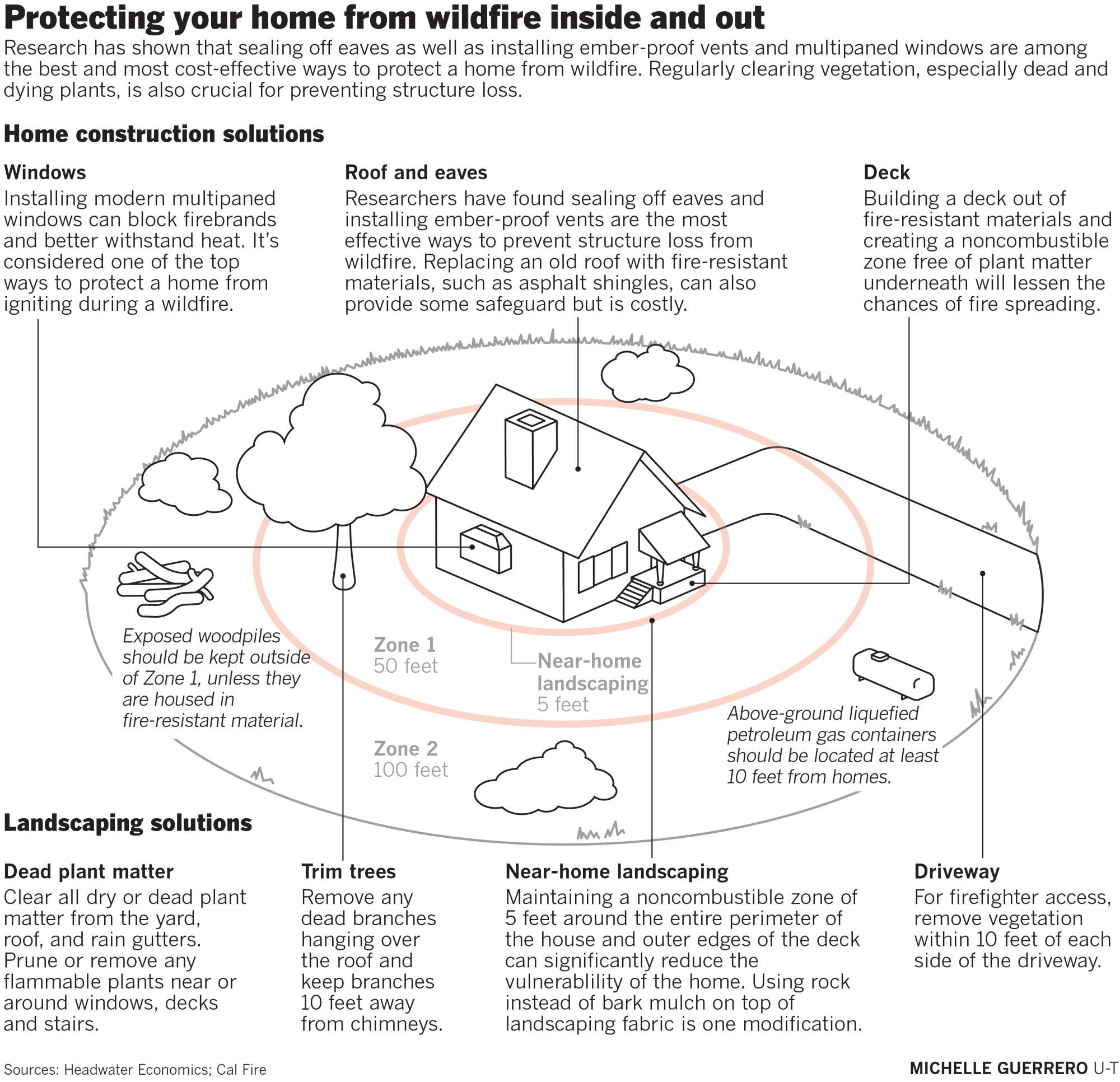

As part of this effort, the state plans to launch a pilot program with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to provide money for home retrofits, such as sealing off eaves and installing ember-resistant vents. The recently approved funding also provides some discretionary money that local groups will likely be able to use for programs such as defensible space assistance and free wood chipping to dispose of cleared vegetation.

“This proposed budget really does represent a paradigm shift in the state’s approach on wildfire,” said California Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot. “This is a quantum-leap investment in upfront action to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire.”

Still, critics say Sacramento’s spending priorities are backward. While landscape-scale vegetation treatments most appropriate for forests would receive more than $500 million, the governor’s budget ponies up just $25 million for the home-hardening pilot.

“This is the tragedy of those numbers,” said Char Miller, a professor of environmental analysis at Pomona College who has written extensively about wildfires. “We know that clearing defensible space is far, far cheaper and more efficient than the massive mechanical clearing that this proposal will fund.”

Fast-moving blazes

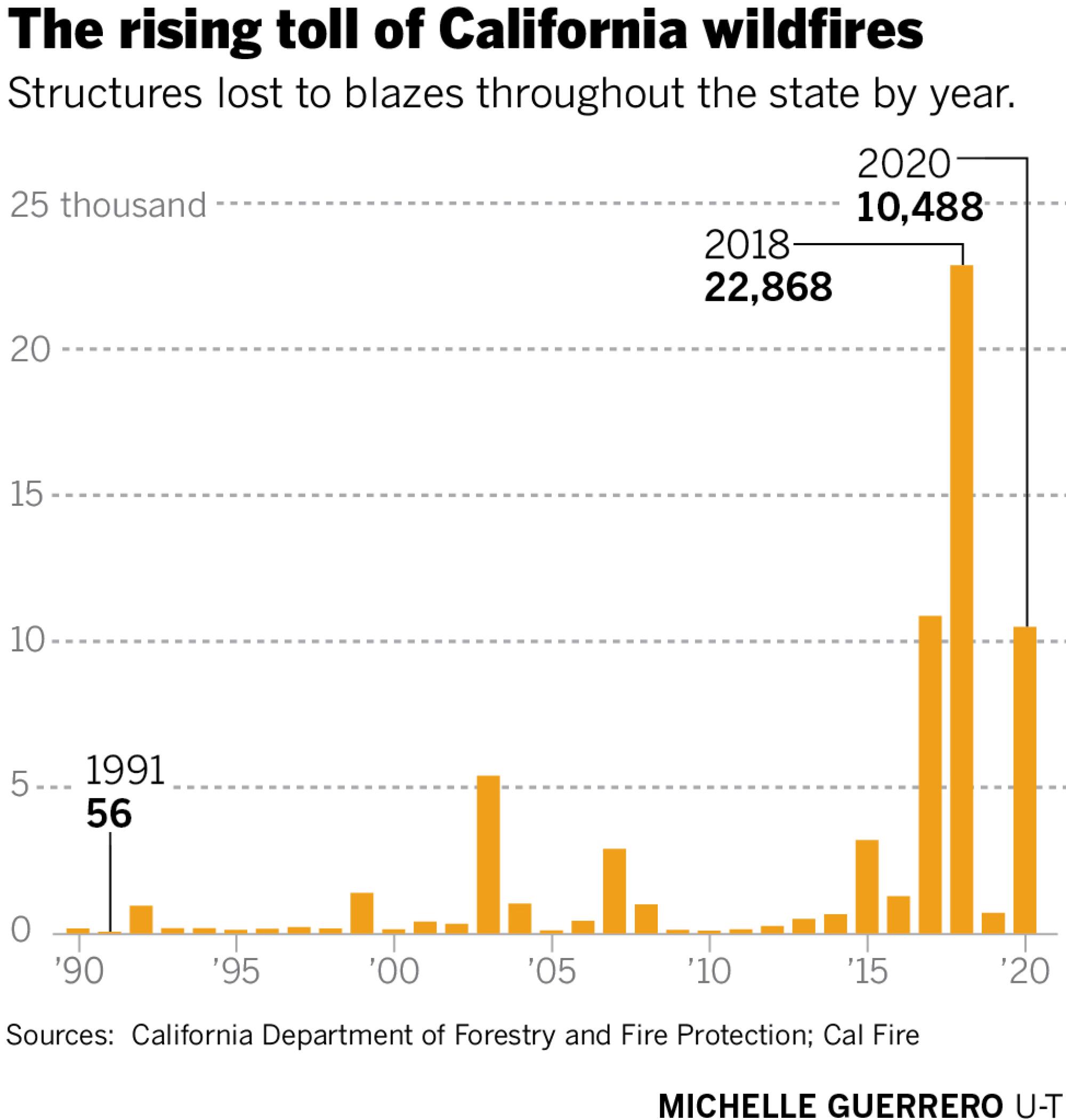

Fifteen of California’s 20 most destructive wildfires have occurred since 2015, following a pattern that overwhelmingly unfolds outside of the state’s most heavily forested areas.

In late summer and autumn, strong wing gusts, often called Santa Ana or diablo winds, have repeatedly whipped up fast-moving blazes though bone-dry vegetation, most commonly shrublands. Those blazes blow embers into nearby communities, where homes explode into flames as firebrands torch unkempt landscaping, slip through vents to ignite attics, and land in gutters filled with dry leaves.

If just one untidy home in a community catches fire, it can be enough to put all the surrounding structures in danger. It’s not uncommon to find an entire subdivision burned to the ground while large pine trees loom nearby relatively unscathed.

Robert Garant knows this and so does the Julian community. The 94-year-old recently had a pacemaker implanted in his chest. With his landscaping routine on hold, the couple fretted about the increasingly overgrown state of their property, especially as the days warmed.

“We tried to do it ourselves,” said Gladys Garant, 86. “He did the best he could every day. I used to drive the tractor and mow. It’s hard. That’s all I can say.”

The Garants said there’s no way they could afford to pay for the work on their limited income. The cost, which included removing numerous dead oak trees, topped $14,000.

Luckily, the couple lives next to a family that started the successful Pope Tree Service. The neighbors helped them qualify for a financial-assistance program, and a crew of workers overhauled their property a few weeks ago.

“I know what this means when they come over here and do this work,” Robert Garant said, still gripping an old chain saw. “I pray to God, ‘Thank you for sending these guys.’”

The Garants were fortunate. But help is hard to come by.

Officials with the Resource Conservation District of Greater San Diego County — which runs the region’s primary defensible-space assistance and free chipping program — says demand always exceeds its resources. In fact, the district doesn’t widely advertise because it quickly goes through the roughly $250,000 it receives annually from San Diego Gas & Electric and the federal government to help homeowners.

“There’s never enough money for that type of work,” said Sheryl Landrum, the district’s executive director. “We’re always desperate for funds to help people keep their property clear.”

It’s unknown exactly how many homeowners in California need financial assistance with home hardening and defensible space. But the $25-million home retrofit program, which is expected to be supplemented by another $75 million from FEMA, could eventually answer that question.

The pilot is required under a law spearheaded by Assemblyman Jim Wood (D-Healdsburg), who said he proposed the legislation in response to concerns from community members who’ve had direct experience with devastating wind-driven blazes, such as the 2017 Tubbs fire.

“It’s one thing to have adequate resources for wildfire preparedness, it’s another to carefully assess what’s needed in home hardening and defensible space,” Wood recently told the San Diego Union-Tribune. “We don’t exactly know what that need is, but we know it’s huge.”

About 15% of the roughly 160,000 homes Cal Fire inspected last year were initially in violation of defensible space rules. Inspectors routinely had to visit homes up to three or four times before homeowners cleared their property.

However, in about half of the cases where a homeowner was in violation of the defensible space code, Cal Fire never followed up with a return visit, according to agency data.

Last year, the firefighting behemoth visited about 20% of the roughly 700,000 properties it has jurisdiction over. Records show that fewer than one in five homes had both sealed eaves and ember-resistant vents.

Dead trees

The debate around whether to log the Sierra Nevada in the name of wildfire prevention started around 2015, at the height of California’s worst drought in recorded history.

In September of that year, wind-driven blazes — already common to Southern California — brought previously unseen levels of destruction to northern parts of the state.

The incredibly fast-spreading Butte fire, for example, sparked when a tree fell on a Pacific Gas & Electric power line, burned through the rugged brush, timber and grass-covered hillsides of Amador and Calaveras counties. Fueled by triple-digit heat, dry conditions and ember-laden winds, the blaze destroyed more than 900 structures.

Just a few days later, faulty wiring of a hot tub ignited grass around a home in the rural community of Cobb, starting the Valley fire. Erratic winds fanned flames mostly through shrub and grasslands, eventually destroying nearly 2,000 structures throughout Lake, Napa and Sonoma counties.

In October 2015, then-Gov. Jerry Brown declared a state of emergency due to unprecedented levels of dead and dying trees in the Sierra Nevada, creating the Tree Mortality Task Force. The call to action emphasized the idea that the forest die-off “significantly worsens wildfire risk.”

The federal government, which owns and manages more than half of the state’s forested lands, got to work removing trees that posed falling hazards along roadsides and power lines. The state’s task force and federal officials helped coordinate the removal of more than 1.5 million dead trees through the end of the decade.

Out of that effort grew the Forest Management Task Force, established in 2018 to “introduce a more holistic, integrated approach toward effective forest management.” Along with continuing to remove dead trees, the task force set its sights on thinning out overgrown forests.

Newsom established a shared target with the U.S. Forest Service last summer to scale up logging and fuel treatments on private, state and federal lands from about 330,000 acres a year to 1 million acres annually by 2025.

As calls for forest thinning have ramped up, so have questions about the extent to which such logging prevents wildfire.

Environmental activists have criticized the thinning projects for removing dead and dying trees that provide valuable habitat for birds, small mammals and other species that feed or make their home in the hollowed-out logs.

They’ve also pointed to an emerging body of scientific literature, largely from the University of Colorado, that found wind and drought conditions greatly overshadow any impact from trees killed by beetles.

Some scientists in California have pushed back on these findings, saying the science isn’t yet conclusive on the extent to which tree mortality drives massive wildfires. They’ve repeatedly expressed worries that logs are piling up across forest landscapes, providing huge amounts of dangerous fuel.

A February 2018 paper from researchers at UC Berkeley suggested the resulting firestorms could resemble the firebombing of Dresden, Germany, in World War II.

They’ve specifically pointed to last year’s Creek fire in Fresno and Madera counties as a prime example. Hot and dry conditions as well as large amounts of woody debris fueled the blaze, which burned 377,693 acres and destroyed 853 homes. The fire was so large it created its own weather system.

The fire burned through parts of the Sierra National Forest that had recently seen vegetation and tree removal. While that didn’t stop the fire, officials said it lessened devastation.

“You had a lot of homes saved because of that fuel reduction work,” said Jessica Morse, deputy secretary for forest resources management at the California Natural Resources Agency. “You need strategic fuel breaks so that people can escape during fire. That’s often what saves a lot of lives.”

However, researchers have acknowledged that forest logging and other vegetation management projects often center less on preventing structure loss and more on protecting natural ecosystems.

A legacy of commercial logging and aggressive fire suppression have left mid- to lower-elevation conifer forests choked with younger trees competing for ever-more scarce amounts of water. The concern is that large wildfires, exacerbated by these conditions, will increasingly damage watersheds that supply agricultural and urban areas.

Malcolm North, a researcher at UC Davis and one of the state’s top authorities on forest ecology and fire, has defended the state’s approach. He said that, if done correctly, forest thinning should help protect the Sierra Nevada against the worst impacts of drought and invasive beetles.

“There’s too many straws in the ground,” he said. “You’re going to get a lot of dead trees unless you reduce the competitive demand for soil moisture.”

He also recently told the Union-Tribune that such projects do little to prevent blazes fueled by high winds and drought, such as the 2018 Camp fire. The state’s most deadly and destructive blaze burned 18,804 structures and killed 85 people, wiping out roughly 85% of the town of Paradise.

“It started in grass under power lines and got into basically chaparral,” North said. “If you had a bunch of dead trees, it’s hard for me to imagine it would have changed the hellacious conditions.”

The science

Every year, the state intentionally burns thousands of acres to thin forests — but those efforts pale in comparison to what nature once did on its own, before humans started fighting fires.

Scientists estimated that prior to the 1800s, wildfire scorched about 4.5 million acres a year throughout California. Today, thanks to billions of dollars spent on firefighting, the annual average is roughly 1 million acres, although 2020 saw more than 4.2 million acres goes up in smoke.

What’s changed most recently is how wildfire affects humans. All but three of the state’s 20 most destructive wildfires have occurred since the turn of the century, with an average of nearly 3,000 structures destroyed annually, according to Cal Fire data.

People have increasingly built homes in the most fire-prone landscapes in the state — rolling, canyon-riven hills covered in oak, chaparral and highly flammable grasses.

Humans also have been responsible for starting about 97% of wildfires, according to a study last year from the University of Colorado.

“The problem is humans igniting fire during wind events,” said Jon Keeley, a senior scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Western Ecological Research Center.

Keeley and researcher Alexandra Syphard published a study in 2019 establishing that many fires throughout the state have little to do with overgrown forests and everything to do with hot, dry and windy conditions. The findings, which came in response to the call for increased forest management, attempted to highlight the need for home hardening and private landscaping.

While logging and other vegetation treatments may prove crucial for forests, researchers have found that clearing chaparral shrublands can increase wildfire risks by inviting the spread of highly flammable invasive grasses.

A follow-up report from that year found that certain structural characteristics of a home significantly correlated with surviving wildfire, most notably having closed eaves, screened vents and multipaned windows.

Syphard, chief scientist for La Jolla-based Sage Underwriters, said she has recently gathered data that bolsters those initial findings.

According to her most recent analysis, wildfire starts in grass, shrub and oak woodlands about 57% of the time, compared with just 14% in conifer forests. Perhaps that’s not surprising, since forests make up less than 20% of vegetation in California.

Even more revealing, however, is that those three landscapes have accounted for more than 60% of all the area burned in wildfires that involved structure loss between 2000 and 2018 — compared with just 12% for forests.

“The fires that result in destroyed structures, a very small percentage of that is in conifer forests, which runs contrary to what most people think,” Syphard said.