Taliban Torturers on the Run

- Share via

KABUL, Afghanistan — In the final hours before the Taliban abandoned Kabul in the dark of night early Tuesday, the screaming stopped in Amniot prison. The torturers were on the run.

Amniot, operated by the Taliban’s intelligence investigation department, was notorious as a place where accused criminals and political prisoners were brought so interrogators could beat confessions out of them.

When the prisoners called out to the guards Tuesday to help a sick prisoner and no one came, the inmates realized that the Taliban had fled the Afghan capital. So the prisoners made their escape, using pieces of a steel bed frame to break open the padlocks on their cells, said Hamed Gulagha, one of the escapees.

Once free, the men found the keys to the women’s cells and liberated them, along with several of their children. The women immediately abandoned the Taliban dress code that forced them to cover themselves in head-to-foot veils called burkas.

“The women were thanking God,” said Gulagha, 25. “They didn’t even put on their burkas.”

Many people celebrated small victories Tuesday after they awoke to find the Taliban gone and thousands of Northern Alliance troops and police streaming into the capital. It is too early to know whether Kabul’s latest liberators will bring more suffering, but the many residents who saw the Taliban as an occupier had good reason to celebrate.

Some put cassette tapes into their stereos and played music for the first time in more than five years. When Taliban forces took Kabul in 1996, they seized every cassette and videotape they could find because they were deemed an offense to God.

The Taliban destroyed the contraband by pulling the tapes off the reels and stringing it up on lampposts. Eventually, residents say, the tangled masses of brown tape fell off and rolled away like tumbleweeds in the wind.

On Tuesday morning, there were snarled pieces of cassette tape lying next to the bodies of several men on a basketball court and in the concrete-lined ditches of Kabul’s Shahr-i-Naw park, as if to explain their executions.

The men--seven in all--had been shot at close range. A spent cartridge lay next to the head of one of the dead men, beside a set of car keys. An empty wallet sat open beside the body of another, who was wearing a brown military camouflage jacket under his winter coat.

Fall of Capital Remarkably Peaceful

Gawkers gathered around each body. One said Northern Alliance soldiers killed the men because they were attacking people.

One corpse had a bloodied, broken stick lying loosely in his right hand, which was raised above his head and lay in a pool of blood.

A few of the dead were Arab or Pakistani fighters for the Taliban, the onlookers insisted, but it was hard to know how they could tell. The foreigners had darker skin, someone said.

Despite the bodies and numerous arrests of men accused of being Taliban soldiers, a feared blood bath had not followed the Northern Alliance’s seizure of Kabul, at least not on the first day.

The city’s fall to the opposition was remarkably peaceful. No street battles erupted because most of the Taliban had fled toward their ethnic Pushtun strongholds in the south and east.

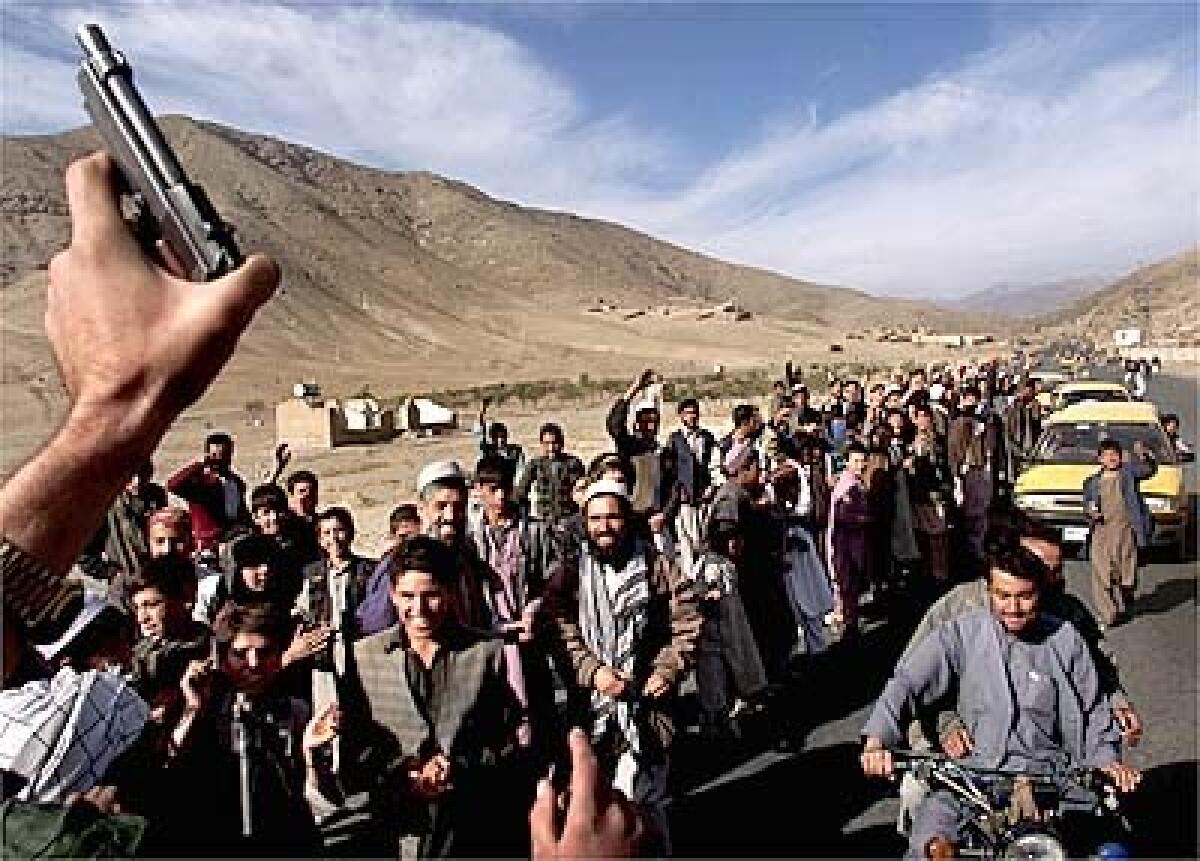

Opposition soldiers took up positions at traffic circles and government buildings, where they were often cheered on by happy crowds.

“Our souls were repressed, and now everyone is happy, not just me,” said shopkeeper Nazir Ahmad, 25.

Journalists were mobbed by gleeful people who couldn’t find any other foreigners to thank on the first day of what many residents called their liberation.

“You are my sister,” one said in strained English after tossing a handful of sparkling confetti on an American photographer. Another thrust his hand through a half-open car window to shake a reporter’s hand.

“Congratulations to all of the world’s people for what you have done for us,” said Wahid Ullah Zafari, 29.

When an armored personnel carrier stopped in traffic with half a dozen Northern Alliance soldiers riding on top, a man showered them with a fistful of afghani notes. The soldiers let the money flutter to the ground. It isn’t worth much anyway.

Only a few shops were open in the city, and at the usually crowded Shazadah money-changers’ bazaar, business was slow. As the Taliban pulled out of Kabul, they looted 42 exchange shops of all the foreign currency they could carry, said money-changer Mohammed Ashraf. They left nothing behind.

Ashraf, a former army colonel, runs his exchange business from a wooden table at the side of the road. He wasn’t robbed, he said, but the Taliban looters picked their way through the market from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. Monday.

U.S. warplanes attacked some of the Taliban as they withdrew, including a pickup truck carrying five Taliban soldiers. The vehicle was making a left turn onto Ansari Avenue about 5 p.m. Monday when a rocket hit it, witnesses said.

The blasted remains of the pickup, a Japanese model favored by the Taliban as battle wagons, sat where it had been hit in the middle of the street. Two boys tried to jack up the front to scavenge what they could from the vehicle’s charred remains.

The Taliban soldiers’ bodies were lined up on the sidewalk. At least two of them were wearing camouflage military vests with ammo pockets. An unexploded rocket-propelled grenade and bits of a machine gun belt had fallen next to the gutted truck.

Freed Prisoner Feels No Sympathy

After his escape from the Taliban prison, Gulagha had no sympathy for the soldiers who didn’t get away. He wishes more of the same for the ones who did.

Gulagha says the Taliban arrested him and his brother, Ahmad Shah, who is in his late 20s, about five months ago and accused them of secretly supporting the Northern Alliance. The two men are ethnic Tajiks, and the alliance is dominated by minority Tajiks and Uzbeks.

Gulagha’s neighbors whispered that he and his brother had been arrested for stealing. But whatever crime he was accused of, the scars on Gulagha’s legs and arms left little doubt about his treatment at the hands of the Taliban.

He said six Taliban soldiers came to his house about 5 a.m. one day and took him away to Amniot prison for questioning. Gulagha said he was locked up in a 6-foot-by-6-foot cell, alone for the first several weeks until he got a cellmate, a man accused of keeping illegal weapons in his home and conspiring to set off terrorist bombs in Kabul.

Taliban Guards ‘Were Always Beating Us’

The prisoners slept on the floor. When a visitor discovered that they were lying on bare concrete, the United Nations provided mattresses, Gulagha said.

The Taliban guards were cruel, he said. “They were always beating us,” he said. “And they used to give us potatoes in water as soup, two times a day, and only one cup of tea in the morning for breakfast.” If a prisoner wanted sugar, he had to buy it himself, Gulagha added.

Every five or six days, Gulagha said, guards would come to his cell, usually at night when he was asleep, and take him to a room, where he was tied to a table. He faced the floor or the ceiling, depending on the whims of his interrogators.

“They laid me down and beat me repeatedly with a pipe or an electrical cable, and told me to confess,” Gulagha said.

The torture went on for two to four hours, he said, and one man always did the grilling. Gulagha identified him as Masoom Khan, who he said was head of the investigations department. Two other men named Rohani and Majroh often assisted Khan by carrying out the beatings, Gulagha said.

“Masoom Khan asked me questions, and when I was tortured, he was always with me with a radio in hand, communicating with spies and friends,” Gulagha said.

About 310 prisoners managed to escape from Amniot on Tuesday. One had to be carried out. He was beaten because a snitch reported him saying that the Taliban was finished, just before the regime’s forces fled.

“They hit him so severely that he was close to dying,” Gulagha said. “We carried him on our backs to a relative’s house.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.