Political Shift Stifles Islamic Anger at U.S.

- Share via

QUETTA, Pakistan — The mullahs on the podium had vengeance in their bellies, they had outrage in their hearts, their anger came out in such a flood of words that some of them got hoarse.

“The time will come when the American heads are on one side and our guns are on the other!” one shouted. “Prepare yourself for jihad, and I assure you that success will be ours!”

Two months ago, these were fighting words in Pakistan. On Oct. 8, a day after the U.S. bombing campaign in Afghanistan began, 10,000 people urged on by religious leaders swept into the streets of Quetta, 50 miles from the Afghan border. The demonstrators burned effigies of the American and Pakistani presidents, set fire to cars, stormed the police station and smashed shop windows.

Small Turnout at Rally for Jihad

But that was then. Anyone who thinks Pakistan is still full of Islamic rage about to turn against the West would have needed to look no farther than Quetta’s Ayub Stadium on Friday. Barely 500 people marched in and took places at the foot of the podium for the weekly rally there. A lone, badly wrinkled poster of Osama bin Laden bobbed in the front row. After a parade of religious leaders fumed at the microphone about jihad, or holy war, the crowd, which had sat almost silent through two hours of speeches, could barely muster a chorus of Allahu akbar (God is great) at the end.

There has been a profound shift in the politics of religious extremism in Pakistan over the last few weeks. After years of quietly supporting radical groups of moujahedeen--holy warriors--in Afghanistan and their radical political promoters in Pakistan, the government of President Pervez Musharraf has begun to rein in the jihad organizations and check their pervasive influence on the nation’s educational, political and social welfare systems.

The president’s recent announcement that he will clamp down on extremist groups at the conclusion of the holy month of Ramadan later this week reversed two decades of policy under which the army quietly supported moujahedeen in Afghanistan--some now blamed for possible links to international terrorism--as a means of creating freedom fighters for a proxy war against India in the disputed Himalayan region of Kashmir.

The result of that support was a network of extreme Islamic political organizations in Pakistan that would be unheard of in such Muslim countries as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Syria and Iraq, which have held Islamic militancy tightly in check. Pakistan’s jihad organizations--groups like Tehrik-e-Nifaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi, Sipah-i-Sahaba Pakistan and Jamiat-ul-Ulema-e-Islam--have in recent years rallied fighters to join the Taliban in Afghanistan, created a group of more than 10,000 madrasas, or religious schools, that dominate education throughout rural Pakistan and openly challenged the legitimacy of Pakistan’s military government.

In Pakistan alone, hundreds of people have been killed in sectarian violence fed by extremist calls to arms.

“The thing to realize is these militant organizations are not shadowy underground criminal outfits. They have offices on the main street of many cities. Their leaders get invited to dinner with ministers,” said a diplomat who follows domestic politics in Islamabad, the capital.

The rising influence of the jihad organizations in Pakistani politics has been a source of concern in the West, raising fears of a Muslim revolution that would topple Musharraf’s government and get its hands on Pakistan’s budding nuclear arsenal--the Islamic bomb.

Ironically, the American air campaign in Afghanistan, which ought to have been the one event that unleashed Islamic extremism in Pakistan, might prove to have been the turning point in containing it.

While violent demonstrations broke out in the weeks after the air campaign began, they have sputtered in recent weeks. Sparse crowds like the one in Quetta on Friday, analysts say, suggest that popular support for militant Islam is not nearly so broad as was once believed. The relative public apathy was all the ammunition Musharraf needed to make his move.

After the Eid al-Fitr feast in mid-December--the breaking of the Ramadan fast--Musharraf is expected to announce measures that will probably include the closing of some madrasas, forcibly introducing a secular curriculum into others and prosecuting the leaders of some jihad organizations. At least three top militants already have been arrested, and more than 20 criminal sedition charges have been filed against militant mullahs in Quetta alone.

The government has also moved to dismantle two militant Kashmiri freedom fighter organizations, Jaysh-e-Mohammed and Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, both of which are on the U.S. watch list of terrorist organizations.

“Everybody’s always feared Pakistan being a failed extremist state with the bomb,” said a Western diplomat in Islamabad. “This is the second- or third-largest Muslim country in the world. And Musharraf trying to turn it around from the Pakistan we feared to the Pakistan we can get along with is a huge story.”

The U.S. ambassador in Pakistan, Wendy Chamberlin, said the key to Musharraf’s success could well be whether the U.S. proffers long-term economic assistance to build on the multimillion-dollar interim aid package it approved after the Pakistani leader agreed to support the U.S. bombing campaign.

“He still is on a very shaky foundation. Yet we will continue to need Musharraf as a strong partner even after the fall of the Taliban, because a lot of these foreign terrorists are going to escape through Pakistan,” Chamberlin said. “We’re going to need him for a long time. And if the U.S. picks up and leaves, Pakistan will become a powder keg again very quickly.”

Some Extremists Could Face Execution

At a heavily guarded police post in Quetta, there is a map of the parade route used by the Muslim faithful as they have marched from mosques to the football stadium on Friday afternoons since the bombing campaign began. The inspector general, Mohammed Shoaib Suddle, said this weekend that it is possible some extremists could face execution under the new policies if their crimes are serious enough.

“It is the madrasas that have been forming the concept of jihad, producing fanatics whose aim is to hijack the country. That is the sort of thing that needs to be stopped, and I think the government is determined to do that,” Suddle said.

Islamic leaders say the government is perilously underestimating the extent of public anger over Pakistani assistance to the Americans in Afghanistan.

“Frightened people make silly choices,” said Syed Munaawar Hassan, who has been acting head of the Jamaat-i-Islami party since the arrest of its chief in the recent crackdown.

“Had it been a democratically elected person, Colin Powell wouldn’t have threatened him,” Hassan added, referring to the secretary of State’s contact with Musharraf, who took power in a 1999 military coup, before the bombing campaign. “Even inside the army, I don’t think he [the president] enjoys the confidence of the officers.”

For years, the conventional wisdom was that the Pakistani army would never brook a crackdown on jihad organizations. But Samina Ahmed, a senior analyst with the International Crisis Group who has studied the Pakistani military, says the notion of a powerful Islamic element within the army is misplaced. The army’s support for jihad groups has always been more tactical than philosophical, she contends.

“The Islamic extremists were supported and assisted and trained in Afghanistan for Kashmir. Now, the message is ‘Never let your clients gain autonomy, because once they gain autonomy, they become a threat,’ ” Ahmed said.

But the threat is a manageable one, she added.

“Yes, extremist groups are well trained and well armed. But as we can see, there’s very little support base. And if the military cracks down, that’s basically going to be the end of it.”

All the same, there are doubts that Musharraf is prepared to rein in Kashmiri fighters in the same way he dropped his support for the Taliban in Afghanistan. By supporting moujahedeen groups that were dispatching fighters to Chechnya and Bosnia-Herzegovina as well as to Afghanistan, Pakistan created a de facto army in Kashmir.

“Without losing a single regular soldier, they have engaged . . . 600,000 Indian soldiers in occupied Kashmir,” said Talat Hussain, a Pakistani journalist who has written about extremist groups--although others question whether that estimate of Indian troops is exaggerated.

“But,” Hussain said, “they didn’t look at the overall political consequences. They didn’t realize that some of those groups would develop their own political agenda.”

More Than 2,000 Sent to Back Taliban

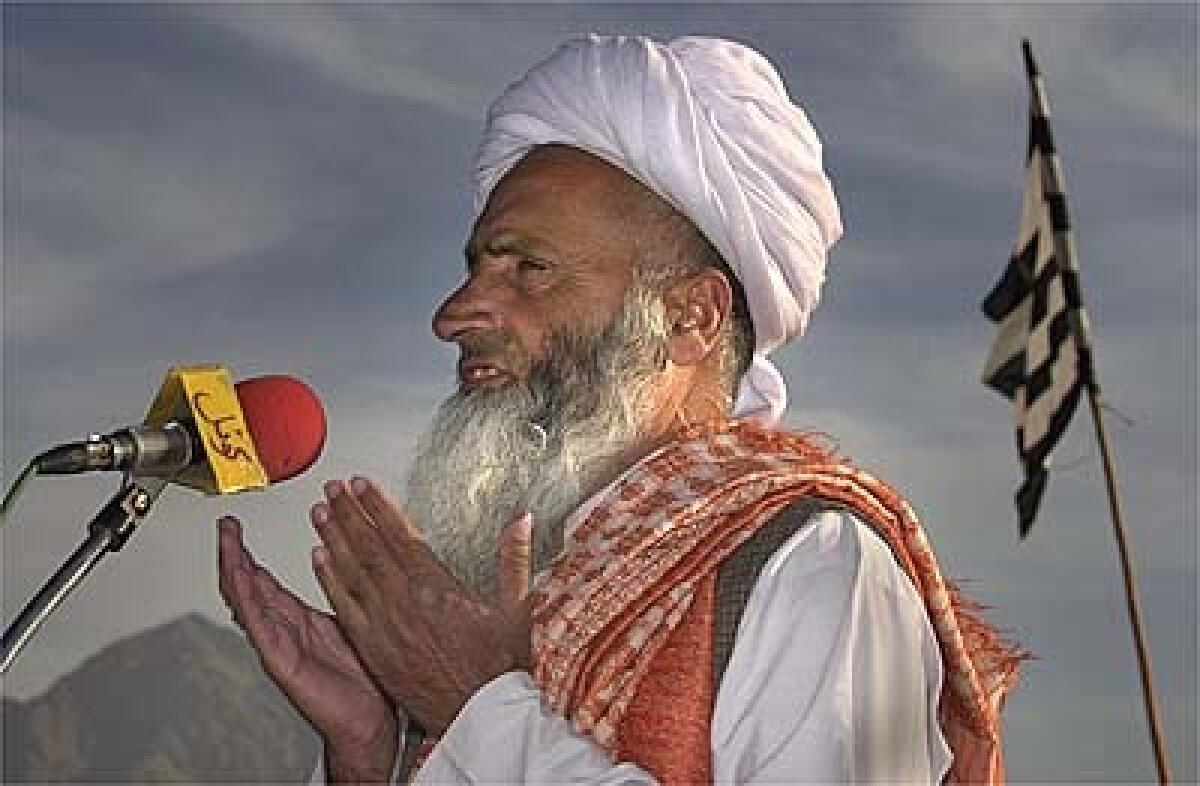

High above a crowded street in the heart of downtown Quetta, Maulana Noor Mohammed, local head of the Jamiat-ul-Ulema-eIslam, sat this weekend on a soft carpet spread out on the rooftop of a mosque. Lightly fingering his prayer beads, he was surrounded by half a dozen followers lazily reading newspapers. The JUI, whose madrasas sent more than 2,000 fighters to support the Taliban in Afghanistan, will probably be one of the groups most affected by the government crackdown.

At Friday’s rally, Mohammed called angrily for a new guerrilla war in Afghanistan to defeat the Americans. He faces criminal charges for a previous speech critical of the government. But in the haze of late morning earlier in the week, and in the quiet monotone of Mohammed’s voice, it was easy to underestimate the implied violence of his aims.

“If the government tries to close our madrasas, then the home of every Muslim will be a madrasa, and we will teach there. If the government stops our madrasas, it will pave the way for us to go underground, and we will then be very dangerous for the government and for the non-Muslim forces, meaning America and its allies,” he said.

“The Americans are only afraid of the nuclear program in Pakistan because they are afraid of the religious forces,” Mohammed said. “If nuclear weapons are not good for mankind, then why is America not ready to get rid of its own? If they are not ready for a Muslim country to have an atomic weapon, why do they keep theirs?”

When the end of the world comes, and Mohammed believes it is near, the Koran says that all religions but Islam will disappear. All men, he says, will accept Islam. “So in this condition, there is no need to use any weapon against anyone,” he said. “But if some forces compel us, then we will use it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.