New Branch Found in Nuclear Network

- Share via

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — Authorities pursuing traffickers in nuclear weapons technology recently uncovered an audacious scheme to deliver a complete uranium enrichment plant to Libya, documents and interviews show.

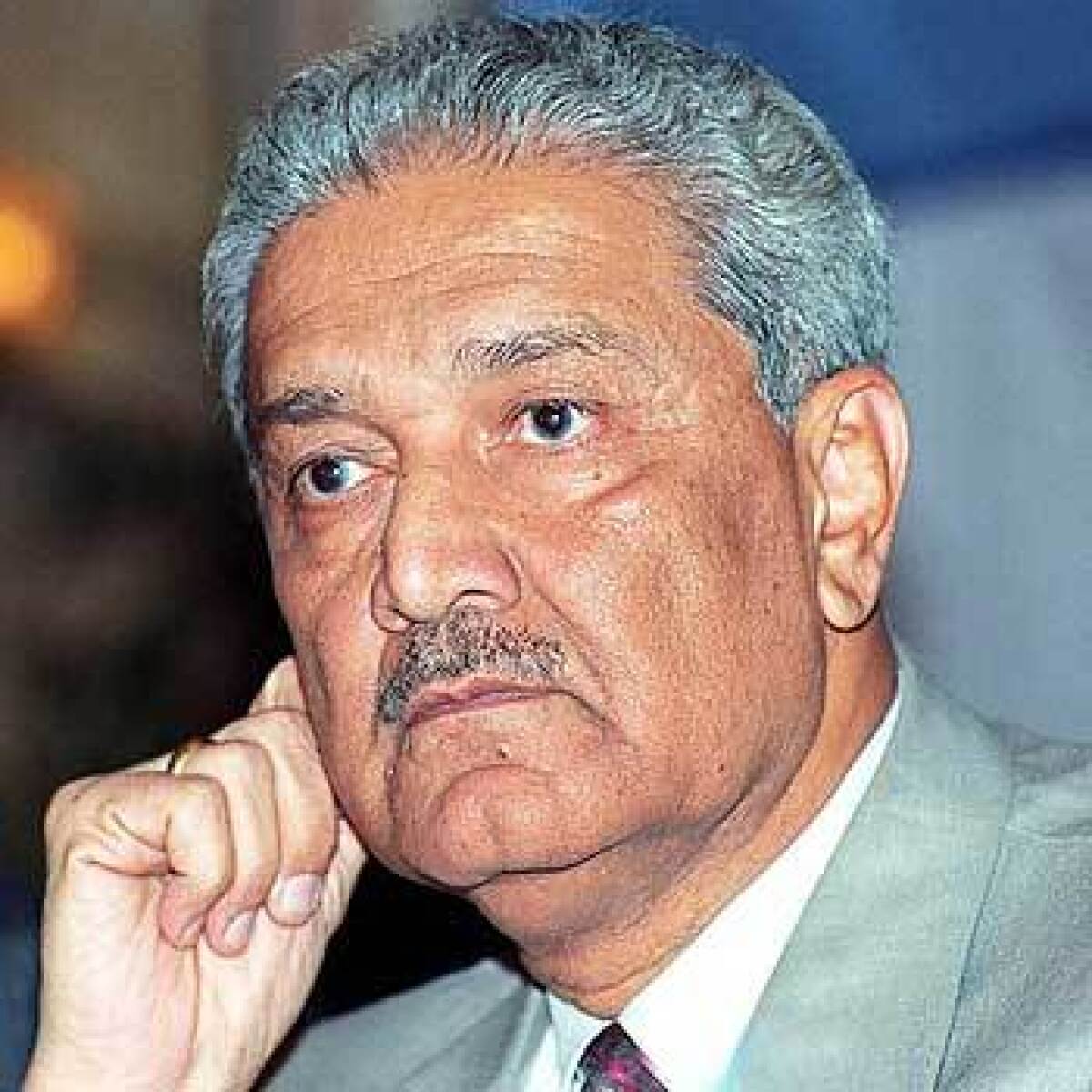

The discovery provides fresh evidence of the reach and sophistication of Pakistani scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan’s global black market in nuclear know-how and equipment. It also exposes a previously undetected South African branch of the Khan network.

The startling dimensions of the plot began to emerge in September, when police raided a factory outside Johannesburg. They found the elements of a two-story steel processing system for the enrichment plant, packed in 11 freight containers for shipment to Libya.

South African officials have disclosed only that they discovered nuclear components. The Times has learned that the massive system was designed to operate an array of 1,000 centrifuges for enriching uranium.

Once assembled in Libya, the plant could have produced enough weapons-grade uranium to manufacture several nuclear bombs a year. Delivery of the plant would have greatly accelerated Libya’s efforts to develop nuclear weapons.

Khan already had secretly shipped to Libya a supply of processed uranium fuel for the enrichment plant, according to later reports by international inspectors.

And some of the centrifuges for the plant were shipped separately from Malaysia. The interception of that cargo by U.S. and Italian authorities in October 2003 led to the Johannesburg raid and spurred Libyan leader Moammar Kadafi to renounce efforts to develop banned weapons.

In the Sept. 1 raid, police found a videotape that detailed the inner workings of Khan’s top-secret government enrichment laboratory in Pakistan, along with trunks filled with designs from the lab.

The discovery of a South African connection to Khan’s web has led to the arrests of four business and engineering figures, including some who had been involved in the former apartheid regime’s nuclear program.

Leads developed in the inquiry have opened up new avenues for investigators from South Africa, other countries and the U.N.’s International Atomic Energy Agency, who are tracing the network’s operations on three continents.

The questions confronting investigators include whether other countries sought Khan’s help and whether tougher restrictions are necessary to prevent a repeat of what officials have called the most dangerous proliferation operation in history.

The processing system found at Tradefin, an engineering and manufacturing company in Vanderbijlpark, outside Johannesburg, had been designed and built over three years. It was then tested, painstakingly dismantled and packed into 40-foot containers, factory records show.

Daniel Jacobus Van Beek, director of South Africa’s counter-proliferation office, participated in the raid and called the scheme “one of the most serious and extensive attempts” to breach international nuclear controls. He estimated that the 200 tons of equipment was worth about $33 million.

Khan, a German-trained metallurgist, used stolen designs and a shadowy network of European suppliers in the 1980s to build the Pakistani plant where uranium was enriched for that country’s first atomic bomb.

A decade later, he resurrected the network to sell nuclear technology on the world market. Secrecy surrounding the Khan ring began to unravel last December, when Libya announced that it was giving up its effort to build an atomic bomb.

As part of a deal negotiated with the U.S. and Britain, Libya disclosed evidence that Khan and his associates had sold Tripoli $100 million worth of technology over 10 years, including designs for a nuclear warhead.

That information led to the immediate shutdown of a Malaysian operation that manufactured centrifuges and sent investigators scrambling to follow up on evidence that the ring had sold enrichment technology to Iran and North Korea.

Under international pressure, Pakistan forced Khan to confess on national television that he had sold the country’s nuclear secrets. Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf pardoned Khan immediately. Investigators from the IAEA and the U.S. have not been allowed to interview the scientist, who is still revered in Pakistan.

As a result, investigators say they are still struggling to uncover the extent of the network.

In the months before police raided Tradefin, one participant said he had pressed his alleged accomplices to “melt down” the equipment, burn the designs and destroy computer files, according to statements to police. But when investigators arrived with search warrants, the evidence was intact.

Enrichment involves feeding gaseous uranium known as uranium hexafluoride into an array of slender centrifuges, which spin at ultra-high speed to transform the gas into weapons-grade material.

The pumps, gauges, valves, piping and other equipment found at Tradefin were designed to control the flow of uranium hexafluoride into 1,000 centrifuges, link them and process the enriched uranium at the end of the cycle, according to interviews, drawings and court affidavits.

Tradefin’s owner, Johan A.M. Meyer, 53, was arrested a day after the raid and charged with trafficking in nuclear technology. He quickly struck a deal to provide evidence in exchange for dismissal of the charges.

Meyer, who worked in South Africa’s uranium enrichment program in the 1980s, admitted in a sworn statement that he knew the complicated system was for a nuclear plant.

But he was unaware that Libya was its ultimate destination, defense attorney Heinrich Badenhorst said in an interview.

In his deal with prosecutors, Meyer implicated two associates, Gerhard Wisser, 65, and Daniel Geiges, 66, according to court records.

Wisser, a German, and Geiges, who is Swiss, both immigrated to South Africa in the late 1960s and became citizens. They were arrested on trafficking charges and freed on bail this month.

Wisser, whom prosecutors portray as the conduit to the Khan network, has long been managing director of Krisch Engineering, a consulting firm in Randburg, a suburb of Johannesburg. Geiges has worked for him since 1978.

Krisch Engineering imported equipment for South Africa’s nuclear program in the 1980s in violation of international sanctions, according to a sworn affidavit from Van Beek, the anti-proliferation official.

During the same period, a second company in Germany that Wisser owned sent nuclear-related components to South Africa. Records show that German authorities revoked the firm’s export privileges after learning of the shipments.

Both Wisser and Geiges have maintained their innocence regarding the Libya deal, saying they thought the equipment was for a water purification plant in an unknown country.

A South African magistrate said the explanations lacked “the ring of truth,” citing Wisser’s experience with the nuclear industry.

A fourth person associated with the South African connection, Gotthard Lerch, 61, was arrested last week by Swiss authorities on a German warrant accusing him of receiving $4.25 million to help Libya develop nuclear weapons. His office outside Zurich was raided the same day that South African police showed up at Tradefin.

An anatomy of the deal, assembled from documents and interviews, shows in stark and mundane ways how the Khan network exploited international businessmen — wittingly or unwittingly — to fashion a web of commerce and intrigue that stretched across the globe.

Encounter in Dubai

Gerhard Wisser was having a tough time finding new business in the Middle East for his engineering company. His fortunes took a dramatic turn during dinner at the home of a wealthy Arab in Dubai in late 1999.Among the guests that night, Wisser has told police, were two men he knew from past business dealings.

One was Lerch. The two men had done business together when Lerch worked for a German manufacturer of vacuum pumps. They remained friends and occasional business partners.

The other acquaintance was Buhary Syed abu Tahir, then 40, a flamboyant Sri Lankan businessman who drove a Rolls-Royce and was living in Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates.

Both Tahir and Lerch had ties to Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program. In the 1980s, Lerch acknowledged supplying vacuum pumps and other equipment to Pakistan.

Tahir also helped Pakistan’s secret nuclear effort and, by the mid-1990s, was coordinating the shipment of technology to Iran and managing Khan’s dealings with Libya, according to a statement he later gave to Malaysian police.

A few minutes into the night’s meal, Wisser recalled in his statement to South African police, Tahir asked whether Wisser’s company could manufacture “certain pipe work systems” for an unnamed client.

Wisser’s firm no longer made piping, but Tahir was not deterred. He offered a generous finder’s fee if Wisser could find another company for the job.

Wisser was in the midst of what he called “a very ugly and costly divorce. I was therefore quite interested to follow the matter up and perhaps earn a good commission.”

Tahir promised to obtain technical drawings for the system and have Lerch examine them before sending them to South Africa. Tahir said the piping was for a refinery in the United Arab Emirates.

“I couldn’t quite believe it, but left it at that,” Wisser said.

At the time, Iran and North Korea were no longer buying nuclear technology at their earlier pace and the Khan network was looking for ways to satisfy an eager new customer — Libya.

Two years earlier, in 1997, Libyan officials had contacted Khan about helping their country’s stalled efforts to build an atomic bomb. The result was a business arrangement called Project Machine Shop 1001.

Tahir, who is in custody in Malaysia, gave police an extensive description of the network’s operation after he was detained a year ago.

Tahir said the arrangement with Libya grew out of a meeting in Istanbul, Turkey, between Khan and Mohammed Matuq Mohammed, head of Libya’s nuclear program.

Unlike Iran and North Korea, Libya lacked the technical expertise or manufacturing base to build the complex plants necessary to enrich uranium and develop a weapon.

As a result, the network had to develop an off-the-shelf enrichment facility for Libya.

Tahir said Lerch was in charge of supplying key parts for the project “by sourcing from South Africa.”

South Africa offered plenty of sophisticated engineering firms and an advanced steel industry. Though the government in Pretoria had voluntarily abandoned its nuclear weapons in 1991, some of the program’s industrial infrastructure remained.

Wisser had used his involvement in that program to justify a request to carry a weapon. In a 1984 application for a gun permit, he told authorities, “I very often carry highly confidential and classified documentation” from the nuclear and arms industries.

At dinner in Dubai 15 years later, the Khan network turned to Wisser, offering him a $1-million commission.

South African Visitor

Returning to Dubai a few weeks later, Wisser brought Meyer, the owner of Tradefin and an old acquaintance from the South African nuclear program. Meyer, who had built an engineering firm after leaving the government, agreed to take on Tahir’s project.Wisser was pleased for two reasons: He looked forward to his “generous commission,” and he was happy to steer some “lucrative business” to a friend.

They intended to call on Tahir. Wisser wanted to introduce Meyer to the people paying the bills. But the Khan associate turned them away.

“Mr. Tahir had no wish to meet Mr. Meyer and insisted that I should rather relay payment requests and other information to him via telephone,” Wisser recalled.

It was not the only oddity in their business relationship: Meyer also was never told where the finished product would be sent.

But whatever doubts Wisser and Meyer may have shared, they launched the project early in 2000 and the money started coming in.

Meyer received direct payments from Tahir, according to investigative reports. Meyer also received prepaid shipments of instruments and other material from outside South Africa, the reports said.

Wisser received the first of three installments on his commission, deposited into a Zurich bank account at a time when attorneys for his ex-wife were scouring the globe to identify his assets. Later payments were sent to his accounts in Dubai and Liechtenstein.

The initial design drawings from Pakistan were of such poor quality that Meyer complained to Wisser. During one meeting, he pointed to an 18-inch stack of design papers and called it “the beast.” Wisser loaned him Geiges to refine the drawings and help supervise the project.

A two-story high complex of pipes and pumps grew in Meyer’s factory, and he received periodic payments from Dubai.

“It was a very ingenious plant,” said Badenhorst, Meyer’s lawyer. “It was one of a kind, a work of art.”

He said Meyer never tried to conceal the project. The work occurred in an open area of his factory, where visitors could see it.

“He knew he was making a system for uranium enrichment somewhere,” Badenhorst said. “He didn’t know where.”

In late 2000, a specialized lathe capable of making uranium enrichment centrifuges was shipped to Tradefin from a company called Gulf Technical Industries in Dubai, according to shipping records.

Peter Griffin, a British citizen who lives on the French Riviera, set up Gulf Technical Industries, and it is now run by his son, Paul, according to records from the Malaysian police.

The Griffins have not been charged; both have said they had no dealings with Libya or with nuclear equipment.

The lathe was supposed to be used in South Africa to manufacture cylindrical rotors for the 1,000 centrifuges. However, Badenhorst said, this part of the project was abandoned because the specialized steel required for the rotors was not available in South Africa.

The lawyer said the lathe sat in the Tradefin factory for several months before Meyer was told to return the machine to Gulf Technical Industries in December 2001.

U.S. authorities later discovered the lathe in Libya, according to a sworn statement by Capt. Benjamin Nel, head of the South African police investigation.

With the South Africans unable to fulfill that part of the contract, the network had to find another source for the centrifuges. In late 2001, Tahir arranged for their production at a factory outside Kuala Lumpur, the Malaysian capital.

Meanwhile, work continued in South Africa. By May 2003, the sprawling stainless-steel structure in Meyer’s workshop was fully assembled and tested. Wisser’s $1-million commission had been paid in full. But Meyer still awaited shipping instructions.

One day that month, two Arabs arrived to inspect the work. They said they were Egyptians, according to Wisser. They stayed at a nearby Holiday Inn and spent a week examining and testing the system.

During their visit, Wisser said, Meyer provided a list of questions for the inspectors — asking, among other things, who was to receive the finished product.

“His questions were never answered,” Wisser said during his 10-hour interrogation by German investigators.

Nonetheless, they pressed ahead. The completed system was photographed, then dismantled carefully and packed in sequence into the 11 freight containers so they could be opened in order and the structure reassembled at its destination.

Shortly after the inspectors’ visit, another payment arrived in Meyer’s South African bank account.

Wisser told German police, “This payment, as an alarmed Meyer told me, came from Libya.”

Sensitive Cargo

On Oct. 4, 2003, a German-registered freighter with the name BBC China painted on its hull left the Suez Canal and entered the Mediterranean Sea. An American spy satellite was tracking its wake.U.S. intelligence had information that the ship was bound for Libya with sensitive cargo. The Italian coast guard was asked to intercept.

The BBC China was forced to divert to the southern Italian port of Taranto. There, five containers were removed and hauled to a nearby warehouse. Inspection confirmed the U.S. intelligence.

The wooden containers bore the stamp of the Malaysian factory used by the Khan network, and they were packed with thousands of parts and components for centrifuges destined for Libya.

The seizure helped persuade Kadafi to pledge to abandon his nuclear, chemical and biological weapons programs and turn over information to the U.S. and IAEA about the Khan network.

The interception was kept secret for weeks. U.S. and British intelligence agents sought to find out as much as possible about Khan’s operation before Kadafi’s public announcement of his decision.

The investigation focused quickly on Tahir, who had arranged the BBC China shipment. In November, acting on information from the CIA and its British equivalent, MI6, Malaysian police took Tahir into custody. He provided authorities with an extensive accounting of the network’s reach, describing its connections in Spain, Turkey, Switzerland, Germany and Dubai.

He did not disclose the South African connection, but U.S. investigators in Libya had discovered the lathe and a trail of import and export records.

In December 2003, American authorities asked the South African government to look into evidence that Tradefin had supplied Libya with restricted nuclear technology, according to investigative records.

The only evidence the South African police could find was that one lathe had been imported from and later returned to Gulf Technical Industries, which had been implicated by Tahir.

The police inquiries set off alarms with Wisser. He told police later that it “dawned upon [us] that something was quite wrong here.”

Still no word came regarding where to ship the cargo containers, which remained stacked in a corner of the factory. When Meyer complained that he still was owed about 15% of his fee, Wisser said he paid his partner about $150,000 from his own pocket.

Wisser also said he urged Meyer to destroy everything. The two-story labyrinth of stainless steel, Wisser said, should be sent to a smelter and melted down. The design drawings from Pakistan, Wisser said, should be committed to “an Easter bonfire.”

Meyer was reluctant to destroy a project that belonged to the unknown client, and his lawyer said that Meyer regarded it as “a work of art.”

So when police arrived at Tradefin on Sept. 1, they found the 11 shipping containers. They also found five trunks filled with photographs, designs, manuals and other documents — an unexpected trove of leads.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.