From the archives: Deadly contractor incident sours Afghans

- Share via

Reporting from Kabul, Afghanistan — Mirza Mohammed Dost stood at the foot of his son’s grave, near a headstone that read, “Raheb Dost, martyred by Americans.”

His son was no insurgent, Dost said. He was walking home from prayers on the night of May 5 when he was shot and killed on a busy Kabul street by U.S. security contractors.

“The Americans must answer for my son’s death,” Dost said as a large crowd of young men murmured in approval.

The shooting deaths of Raheb Dost, 24, and another Afghan civilian by four gunmen with the company once known as Blackwater have turned an entire neighborhood against the U.S. presence here.

Already enraged by the deaths of civilians in U.S. military airstrikes, many Afghans are also demanding more accountability from security contractors who routinely block traffic and bark orders to motorists and pedestrians.

As the war escalates in Afghanistan and the U.S. seeks to win over a wary public, incidents such as the one that left Raheb Dost dead raise uneasy ghosts of the Iraq war. With more than 70,000 security contractors or guards in Afghanistan and billions of dollars at stake in lucrative government contracts, the consequences of misconduct are significant.

A June report by the Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan cites serious deficiencies among private security companies in Afghanistan in training, performance, accountability and effective use-of-force rules.

The report says U.S. authorities in Afghanistan have not applied “lessons learned” in Iraq after a 2007 incident in which Blackwater guards shot and killed 17 Iraqi civilians in Baghdad. Iraq revoked the firm’s license, and five contractors face U.S. federal manslaughter and weapons charges.

The Afghan Interior Ministry has stepped up licensing of security contractors and is demanding stricter monitoring. The ministry says it wants limits on the number of contractors here, even as the Pentagon considers hiring a private security firm to provide more guards for its military bases.

Members of parliament, responding to complaints from constituents, have proposed legislation cracking down on contractors.

“They have caused some serious difficulties for the people,” said Fazlullah Mujadedi, a member of a parliamentary commission looking into security companies.

The extent of those difficulties is hard to gauge: The United Nations office in Kabul, the capital, didn’t break out contractor involvement in its recent report on deaths or injuries of civilians, and other agencies here don’t track such incidents.

In June, Afghan President Hamid Karzai accused Afghan guards working for U.S. forces of killing a police chief and four police officers in the southern city of Kandahar.

The U.S. military called it an “Afghan on Afghan incident” and said no U.S. forces were involved.

Such incidents have fed a sense among some Afghans that private gunmen are above the law -- both Afghan and American. Security contractors are subject to Afghan laws, but the four contractors in the May shooting left for the U.S. before Afghan authorities could mount a case against them.

Since February, oversight of security contractors in Afghanistan has been entrusted not to Congress or the Pentagon, but to a British-owned private contractor, Aegis. The company was hired by the American government after the U.S. military said it lacked the manpower and expertise to monitor security contractors. Aegis is supposed to help U.S. authorities make sure contractors are properly trained, armed and supervised.

The wartime contracting commission, set up by the U.S. last year, expressed concern over “limited U.S. government supervision” of private security contractors in Afghanistan. Many are unlicensed and unregulated, said Zemaray Bashary, an Interior Ministry official.

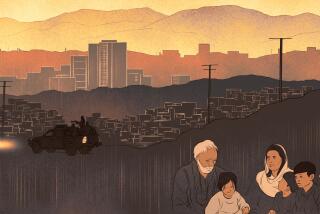

Anger toward hired gunmen runs especially high in Yaka Toot, a densely packed neighborhood in east Kabul, where residents are still simmering over the May shooting.

Residents say the U.S. contractors opened fire without provocation after one of their vehicles tipped over in a traffic accident. Killed along with Dost was Romal, 22, a passenger in a Toyota sedan on his way home from work. Like many Afghans, Romal used just one name.

Mohammed Shafi, a neighborhood elder who said he ran to the shooting scene that night, said the Toyota driver told him that the Americans ordered him to stop, then told him to move on. When the driver began pulling away, Shafi said, the Americans started shooting.

Dost, who was walking about 200 yards away, was shot in the head. No weapons were found in the Toyota, or on Dost, according to an Afghan police investigator.

“Some Americans think all Afghans are terrorists or insurgents,” Shafi said.

“But if they keep killing civilians, I’m sure some Afghans will decide to become insurgents.”

Daniel J. Callahan, a Santa Ana lawyer representing the four contractors, said the men fired in self-defense after one car rammed one of the contractors’ two SUVs, forcing it into a ditch, and a second car tried to run down two contractors.

Callahan accused Blackwater, now called Xe, of “trying to make them scapegoats to take the heat off Blackwater.” He said the company falsely accused the men of drinking alcohol that night.

In fact, Callahan said, Xe supervisors issued the four men automatic rifles and told them to escort Afghan interpreters home that night. He said military investigators found no evidence the men had consumed alcohol.

A U.S. military spokesman in Kabul said in May that the four contractors, who trained Afghan security forces, were authorized to handle weapons only when conducting training. At the time of the 9 p.m. incident, he said, they were not permitted to have weapons.

Xe has said that the four men were fired for not following terms of their contract. An Xe spokeswoman, Stacy Capace, did not return phone calls and e-mails seeking comment.

A U.S. Justice Department spokeswoman declined to say whether the contractors are under criminal investigation in the United States. Callahan said the Justice Department has told him it is conducting an investigation.

Callahan, who called the contractors “four good Americans,” identified them as Chris Drotleff, Steve McClain, Justin Cannon and Armando Hamid.

The Interior Ministry has licensed 39 security companies employing 23,000 people who are assigned 17,000 weapons. More than 19,000 of the employees are Afghans.

The U.S. military employs 4,373 private security contractors, according to the wartime contracting commission. More than 4,000 are Afghans, many of them former militia fighters who help guard U.S. and coalition bases.

The State Department employs 689 security contractors, most for U.S. Embassy security. American employees traveling in certain areas are protected by Xe contractors supervised by State Department security agents.

The U.S. spent between $6 billion and $10 billion on security contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan from 2003 through 2007 alone, according to Congress.

In all, there are more than 71,000 security contractors or guards, armed and unarmed, in Afghanistan, said P.W. Singer, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who has written extensively on the subject.

Private security convoys are a common sight on Kabul’s traffic-clogged streets. Some race past in SUVs with tinted windows, sealing off traffic lanes and forcing motorists to the curb.

Many businesses hire uniformed guards armed with assault rifles. Kabul restaurants that cater to Westerners employ armed, uniformed guards who operate security gates and metal detectors.

The U.S. Embassy in Kabul, citing poor performance, fired its private security contractor, MVM, in 2007 and hired another American-owned company, ArmorGroup North America.

If U.S. or Afghan authorities don’t properly monitor companies such as Xe, those firms should answer in person to the families of civilians killed or wounded by contractors, said Raheb Dost’s aunt, who goes by one name, Friba.

“We want to confront them and ask them: Why do you think you’re allowed to do such a terrible thing?” Friba said, standing over her nephew’s grave.

Mirza Dost, the dead man’s father, said he was summoned to a police station in May to meet U.S. Embassy officials and Americans who told him they represented Xe. He said the Americans apologized and agreed to pay hospital bills for his son, who was in a coma but later died after 31 days in the hospital.

After his son’s death, Dost said, he was paid “a good sum of money”; he declined to elaborate.

Shafi, the neighborhood elder, said the family of the other man who was killed was also paid.

Dost, who lost a leg to a land mine fighting the Soviet army in 1989, said his son was the family’s sole wage earner. He said he considered Xe’s payment fair compensation but was offended that neither the embassy nor Xe paid a condolence call after his son died.

“That’s our culture, but the Americans don’t know our culture,” he said.

Dost said he does not blame all Americans, but he is wary of any American contractors or U.S. forces he encounters on the street.

“They need to be more careful and show more respect for Afghan people,” he said.

Security contractors sign contracts making them liable for prosecution for violating Afghan laws. But Dost does not insist that the Xe contractors be tried in Afghanistan. Nor does his neighbor Shafi, the community elder.

“It wouldn’t make me happy to see them face Afghan justice,” Shafi said as young men from the neighborhood leaned across Dost’s grave to hear his pronouncement.

“What would make me happy,” Shafi said, “is to never have another innocent person killed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.