In Pakistan, the displaced yearn for home

- Share via

Reporting from Mardan, Pakistan — Any early novelty is long gone. Time drags and insecurity weighs heavily. For many of the 11,000 residents of the Sheik Yaseen displacement camp, six weeks in with untold more to go, homesickness and a sense of dislocation are quickly intensifying.

On a breezy day, as the wind whipped up garbage and dirt, a fine dust settling on tents and in eyes, thoughts turned to home. For most in Sheik Yaseen, that’s the Swat Valley, a former tourist haven once dubbed “the Switzerland of Pakistan,” which they fled when the army launched its offensive against Taliban militants.

Now, as the army prepares to launch a new offensive in the tribal area of South Waziristan, 200,000 temporarily displaced Pakistanis may be added to the estimated 2 million already forced to leave their homes.

Those in this camp say they wish their fate on no one else.

“Everybody loves their own land,” says Mian Sedi Jan, a retired driver from Mingora in Swat who doesn’t know his exact age -- eightysomething -- but remembers driving to Bombay before Pakistan and India split in 1947. As children huddle around him, he whacks at them with a stick for getting too close to his spot on the floor of the tent he shares with his wife. “We just want to go home. It’s the sweetest place on Earth.”

The Pakistani government, under pressure from the U.S. and a growing number of its own citizens, sees the human cost as necessary for driving out the Islamic militants who have increasingly threatened state authority, destroyed girls schools and beheaded critics.

At the camp, however, people seem divided on whether the Swat offensive has been worth the huge price in property, lives and inconvenience.

For Mursleen Khan, a 34-year-old Swat resident, it’s the peaches that weigh most heavily on his mind. This is peak harvest time, when the boughs groan under the weight of the sweet fruit, and sharecropper Khan is distraught that fighting has kept him from his orchard, which provides the bulk of his livelihood.

“I’m here and they’re there,” he says. “It’s about all I can focus on right now.”

With no work, little distraction and no place to go, many camp dwellers find little to focus on but the unpleasant conditions, and tempers can easily flare.

“The tent’s too hot, the kids are uncomfortable, there’s not enough water, and I have no work,” says Fazal Rabi, 45, living in one of the long rows of look-alike tents with his wife, eight daughters and two sons. “We want to go home soon, God willing.”

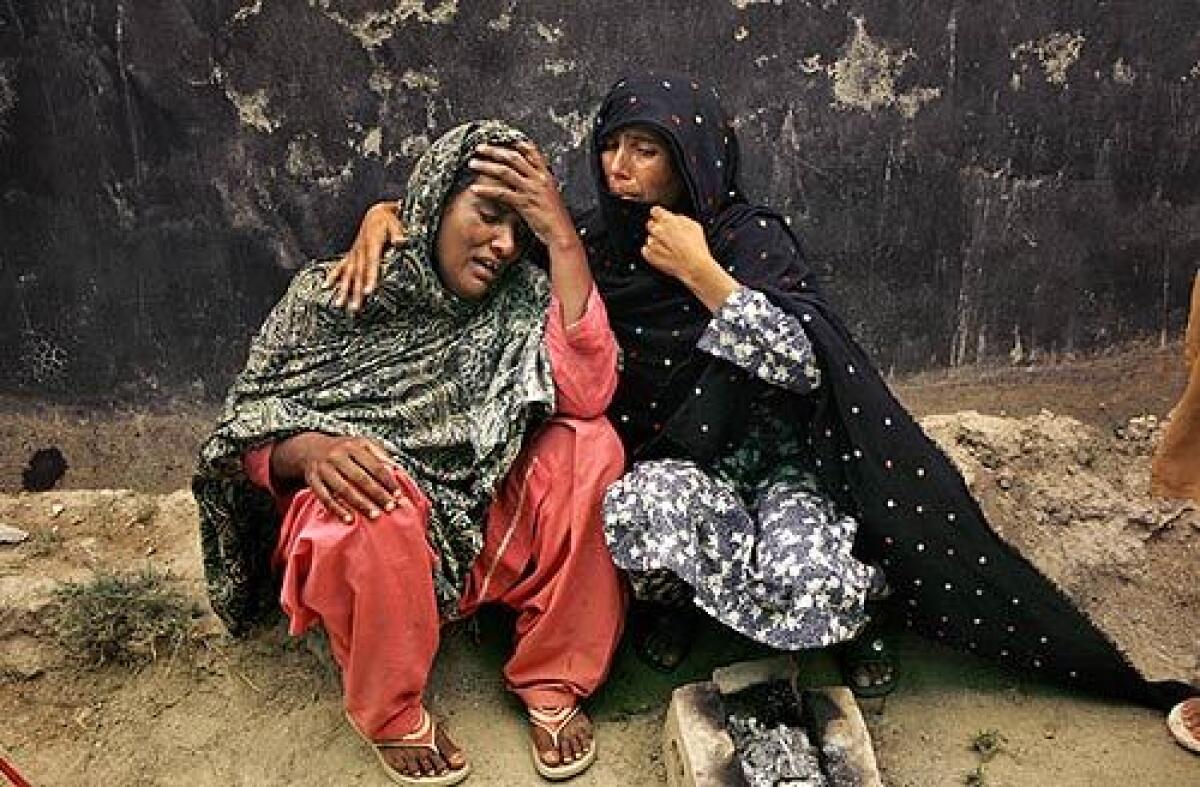

An ambulance pulls into the camp loaded with three wailing women and the body of a 70-year-old woman. The arrival draws a crowd of bored camp dwellers to watch six men carry the corpse to an area behind a plastic tarp. It takes some shouting and scuffles with the crowd for relatives to gain some privacy in which to grieve.

Even the souls of the dead -- the deceased woman had developed stomach problems and a high fever after her family was forced to flee Mingora -- want to return to Swat, says Sahib Zada, a relative who blamed the death on an overtaxed medical system and move-related stress.

“We want to bury her in her home village, but the government has blocked the road,” Zada says. “Now we’ll have to bury her here in the camp. Ideally, she should enjoy her final rest at home, and it is very disturbing not to see that.”

Government officials struggling to address the huge humanitarian crisis have announced that displaced people should be able to return to Swat within a week or so.

Those living in tents, however, note that new arrivals daily from Swat speak of continued fighting, hardly ideal conditions for going home.

“All this uncertainty and confusion creates real mental tension,” says Sher Ali, 19, a photocopy shop employee from Mingora. “And when we do finally go back, who knows whether we’ll find our house destroyed by all the fighting.”

People will return when they feel secure, but that involves more than an end to armed conflict, says Manuel Bessler, Pakistan director of the U.N. Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Necessary conditions include the resumption of electricity, water, reliable healthcare and law and order.

“We’re not there yet in a lot of places,” Bessler says.

Given the army’s use of bombs and the employment of artillery by both sides, people dread the reconstruction needs that may greet their return. One humanitarian group recently held classes at the camp on carpentry, mixing concrete and other basic building skills.

“The first thing I’ll do after getting back is check that my house isn’t wrecked,” says Fazal Wahel, 37, a furniture salesman from Mingora, whose family members attended the classes. “The second thing I’ll do is go see my friends.

“It’s such a tragedy that our beautiful Swat has suffered so much. We don’t want the army. We don’t want the Taliban. All we want is peace.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.