Everything must go

- Share via

On a conspicuous corner of Wilshire Vista, passersby slow down, stop, take a closer look, break into smiles. The house before them bursts onto the landscape with the mad exuberance of a Mardi Gras float, vibrating with life force in the midst of the monotonous rows of buff and putty stuccos that line the streets of this mid-city neighborhood.

“Whoa! Cool!” A driver calls out from his SUV on an afternoon in early July. “You live here?”

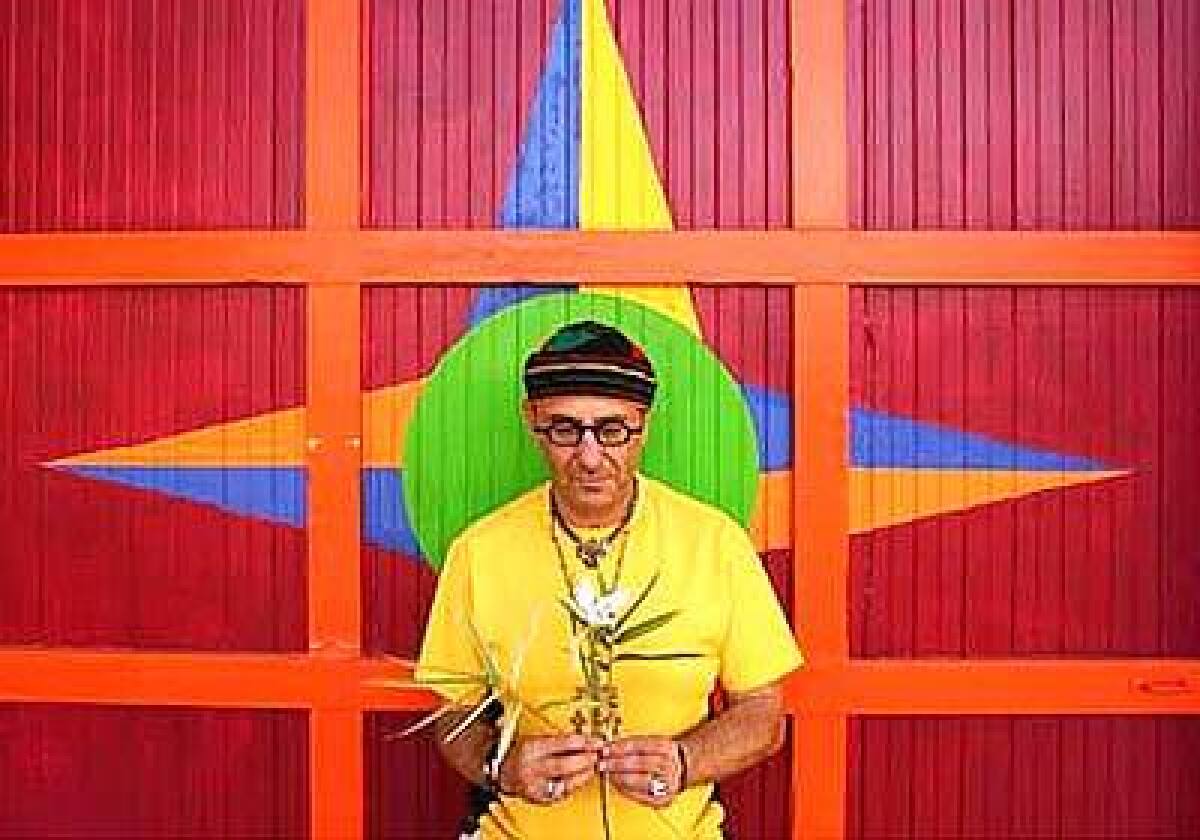

No, Harry Segil does, for the next few weeks, at least. The furniture designer emerges at that moment through the sculpted metal side door and comes down the stoop — painted with stripes in the same tones that have turned his Spanish Revival into “an iconic art piece,” as he puts it, a Technicolor confection of orange, magenta, deep-sea blue and apple green.

He’s sorry, his stereo — spilling samba from the second-story windows — must have drowned out the doorbell. A woman bicycling with her daughter rounds the corner.

“You’re moving?” she asks him, pointing to the “In Escrow” sign in the front garden. “Oh, no. The buyers won’t change anything, I hope,” more a plea than a statement. “We come this way every day because your house makes us so happy.”

Harry hears this, or something like it, on a regular basis, he says, shaking his head with pleasure. It just makes it harder, what he’s going through, about to walk away from it all.

The exterior only remotely prepares you for the interior, in the way a guidebook description of desert heat would prepare you for a high noon hike in the Mojave. It’s a giant-size crayon box of color, a tumult of patterns and shapes and textures that electrify the atmosphere.

The visual overload makes me momentarily lightheaded. Even Harry’s attire is in concert with these surroundings, his home for 16 years. His baggy, bright-rust pants and graphic black and white shirt, coordinated with checkered and orange canvas shoes give him the hip aspect of a man much younger than 57.

Sitting on one of his own designs, a sinuous leather sofa in repeating primary colors, he pours tea into porcelain cups and surveys the living room. “Everything will go,” he says with a sweeping toss of his hand and a grimace of a grin. “Everything.”

He has decided to rid himself of the whole caboodle, except perhaps his bed, a few chairs, a table or two, a piece of art — he’s still deciding. “I’m facing the dilemma of so much of my generation,” he says, meaning the post-50 baby boomers, aging en masse, who long to be released from the hassle of caring for large properties and lots of things, but who struggle with the magnitude of the decision.

They’ve had their mid-life crises: Call this mid-life opportunity. Time to unload themselves of burdens. Live unencumbered, not possessed by their possessions. Maybe live out a few unfulfilled fantasies if they feel like it: Free up their homes, free up their psyches.

Seven of these boomers turn 50 every minute. They’re driving what builders and housing researchers expect to be the fastest growing trend in the housing market during the next decade — smaller homes with better amenities to lighten the load of chores. Already, the signs are evident: Condo/co-op sales have reached record highs, and the square footage of the average new home has stopped increasing.

“It’s time,” says Harry, who is divorced and whose two sons are grown and firmly established. I’m committed to downsizing to a simpler way of life.”

By the end of the month, he’ll be ready to move to his new home, an industrial open-plan loft space in Culver City that will incorporate his living space and studio.

On this particular July day, his journey, as he often refers to it, has begun, fraught with no small measure of ambivalence and trepidation. “My home, like everyone’s home, is charged with my history. Every item tells a personal story.” Perhaps that’s why he’s put off the inevitable until just 3 1/2 weeks before the new owners are scheduled to move in.

For a man staring at the task of divesting himself of decades’ worth of objects, including inherited pieces, he seems reasonably confident, in a rickety sort of way — shadows of doubt creep in from time to time and darken his optimism. But they pass almost fast as they appear. “Well, I have to, don’t I? There’s no choice. It has to go.”

A statement like that can’t be made nonchalantly when you’re speaking of belongings on the order of Harry’s. They’re valuable, many of them, and covetable, most of them, and they number, I quickly calculate, in the thousands. He goes through the nine rooms, opening cabinets and drawers to reveal 30 years of over-the-top collecting. In a word: crammed. In two words: too much. And he is the first to point it out. Stuff, all that stuff.

Huge armoires, centuries old, hog wall space next to important Mid-Century designer pieces by the likes of Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen and Alvar Alto blithely mix with several of Harry’s famous creations.

“It’s almost the history of design for the last three centuries,” says Carolyn Mani, director of Sunset Estate Auctions at Bonhams & Butterfields, which will auction off a few of the most important pieces Oct. 17.

In the mid-’80s, Harry took the design world by storm after he opened an antiques showroom on La Brea, the HarRy Gallery, and began to fill it with wildly inventive furniture that he had first made “just for fun, just for myself.” Like him, it had big personality — a whimsy and theatrical posture that, from the get-go, captivated celebrities: Madonna, Cyndi Lauper, Diane Keaton, Robin Williams, Philippe Starck, Valentino: In they came, out they went with his furniture.

Before long, he attracted international attention. Publications from France to Israel to Saudi Arabia ran stories about HaRry Art Furniture, as it was known. They viewed it as quintessential L.A. and a seminal expression of American pop culture and everything it conjured: pink Cadillacs, palms, rock ‘n’ roll, neon signs, the myth of Hollywood. It appeared in commercials. for Budweiser, Pepsi, Nike, McDonald’s, Mattel, General Motors.

The NBC peacock chair? HaRry art.

His bold and energetic pieces pushed the limits of furniture design with their witty mix of materials and styles: cast-iron legs with lacquered backs, say, and a ‘60s picture on the side covered with vinyl. If he was capturing American pop culture at its most vivid, he was also recapturing his roots: the profusion of colorful flora from his native South Africa that affected his aesthetic sensibilities early on. “The universe is filled with color,” he says. “There are no beige or gray flowers.”

Although his designs were suggestive of any number of influences — Noguchi, Vladimir Kagan, Art Deco, ‘50s diners, Warhol, Hockney, Dali, tribal African art — they were wholly original.

But in 1992, he decided he’d had enough. “I couldn’t stand all the attention anymore,” he says. At his peak, he closed the high-profile La Brea shop. He moved to his old 4,000-square-foot warehouse on Venice Boulevard, which “remained a full, cluttered space until the past January, when I closed it, too.”

His mother’s death three years ago precipitated a long period of introspection, during which it became clear to him that he had to make drastic changes: “My house and my life were cluttered up with the past.” It takes an event of this enormity, he believes — death, divorce, illness, loss of a job — to shock you into the reality of “who you want to be and how you really want to live.”

Working every day and night for five months, he cleared out the warehouse: sold some things, tossed some, hauled five truckloads away to a thrift store. “It gave me the courage to take on my home,” he says. “Now I’m fighting the dragon.”

He’s doing this not so much because he’s tired of dusting all those surfaces and ceramics in the 3,300-square-foot house, but because he wants “new adventures and new experiences. We hold onto possessions and tired relationships, and eventually they tie up our emotions in barbed wire,” he says. “But it’s a helluva task to let go of them. I mean, there have been times during the last few weeks when I’ve felt choked, unable to breathe, numb, terrified. It’s painful on every level.”

With a small crew of hired help, he manages to sell off the bulk of the house’s contents to dealers, friends, strangers who hear about the last-weekend estate sale.

Now, a month later, he’s set up a well-lighted living quarters in less than 800 square feet, with a mere six or seven pieces — easy, functional pieces by ‘60s designers. And very little adornment. “In this one small area I can read, listen to music, cook a meal, exercise, entertain friends, sleep or do a creative project. It’s as much as I’ll ever need.”

Well, make that as much as he needs for a while. He admits it’s a way station.

“I’m weaning myself from the traditional kind of suburban houses to create a bridge to the next place. I can live here without so much sentimental attachment to the place. When I’m ready to leave next time, it’ll be easy. I’ll just up and go.” Lately, he’s pared down his look, too. Elegant tailored slacks, custom shirts, a ring and a watch. Neutral tones. Some of the time, at least. With his shaved head and postmodern round glasses, he’s sort of Ben Kingsley meets Swifty Lazar.

The simplicity and “the huge weight of responsibility” that’s off him is already beginning to do what he hoped it would: Fresh ideas for designs, he says, are “engulfing his mind.” The inspiration has struck to create an “institute of creativity” in his studio, open it up for lectures, exhibitions, workshops.

His new palette? White. White? Harry Segil, living without color? “White is a combination of all colors,” he corrects me. “And besides, I can be colorful in white, I can be colorful naked, I can be colorful swinging from the treetops. But don’t worry. I’ll stick with the white part for now.”

*

Barbara King, editor of the Home section, can be reached at barbara.king@latimes.com