Architect Smiljan Radic is known internationally for his design of a temporary pavilion for the Serpentine Gallery in London in 2014. But in his home country of Chile, he has produced thoughtful designs that range from restaurants to homes to museums.

The museum is housed in a neoclassical building that was completed in the late colonial era (early 1800s) and served as the royal customs house. The structure surrounds a pair of interior courtyards. The first of these greets visitors with an admissions desk, a shop and a small cafe. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

One of the more striking features of the building is the way Radic redid the stairs that lead to the principal galleries. Gone are the creaking wood steps typical of colonial era structures. Instead, a coal-colored concrete staircase adds a contemporary touch. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

A three dimensional bas relief map at the rear wall charts the locations of pre-Columbian cultures throughout the Americas. The steps add some interesting geometries to the symmetrical nature of the neoclassical building. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The real drama, however, is taking the steps down to the underground gallery. The dimness and coolness of the concrete makes it feel as if you are descending into a hidden archeological site. This is the view up, with a sliver of light penetrating the concrete from above. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

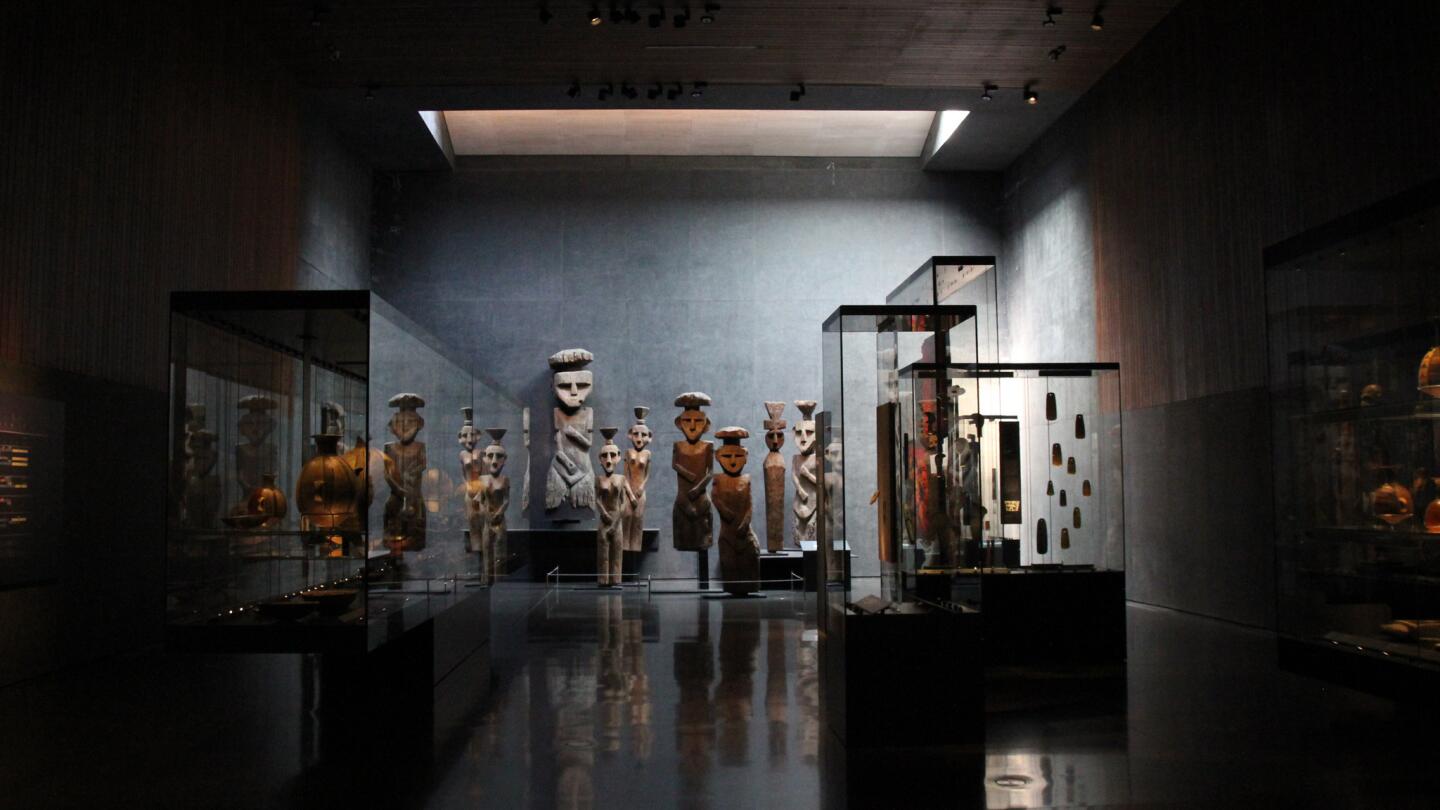

Radic’s redesign kept the colonial structure in tact, but added gallery space underground: this dramatic, nearly 5,000-square-foot hall with 25-foot ceilings that features pre-Columbian pieces from all over Chile. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

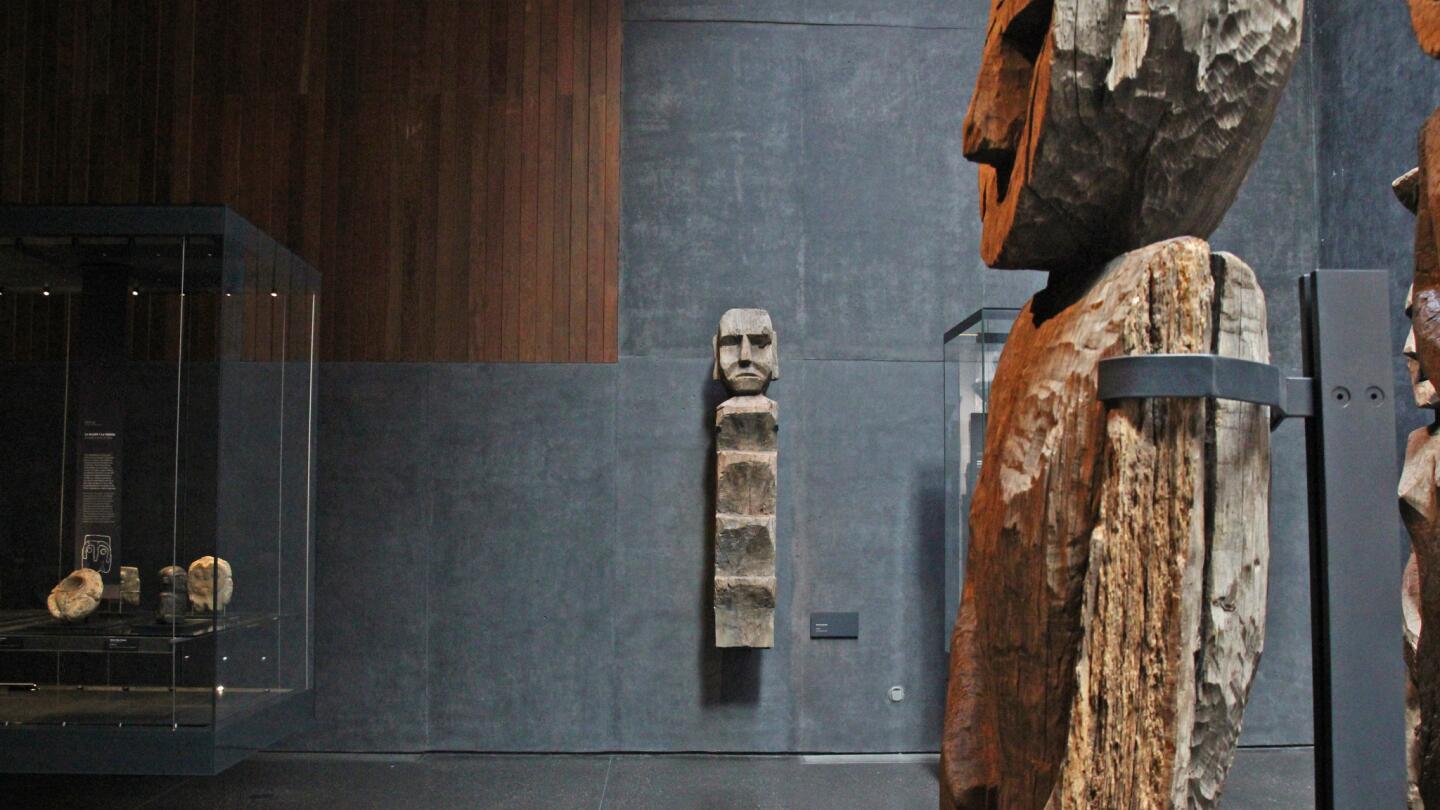

The room is lined with brut concrete and Amazonian woods, the latter providing an element of warmth. In this image, the sculptural wooden totems that once marked the graves of Mapuche leaders, an indigenous Chilean ethnicity. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

The subterranean gallery contains some of the most important pre-Columbian treasures ever uncovered in Chile. The dim lighting allows for the display of delicate textiles. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

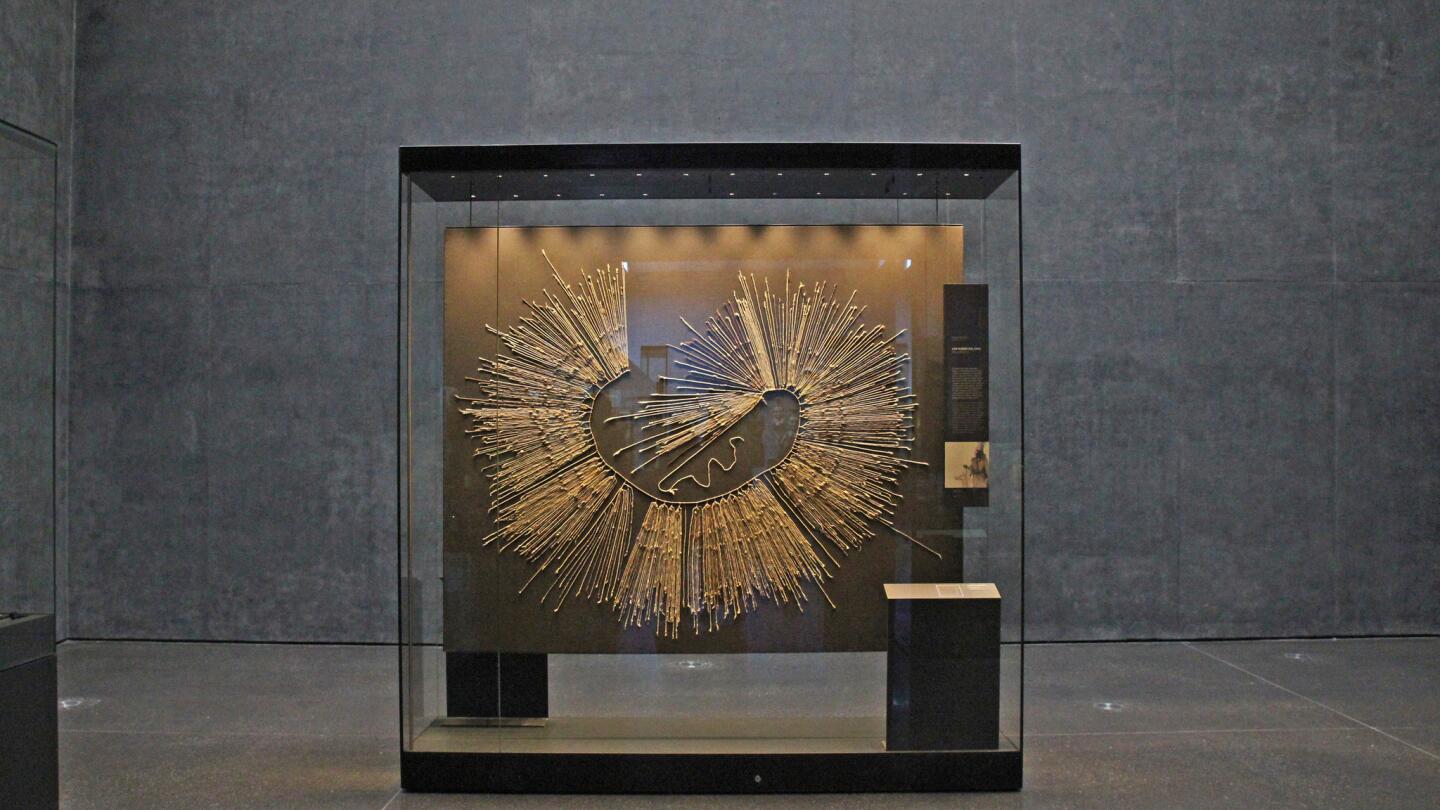

A massive quipu -- the record-keeping system of threads and knots used by the Incas -- is given its own display case on one side of the gallery. This example was unearthed in the northern Chilean city of Arica, which once was part of the Inca empire. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

The upstairs galleries adhere to the traditional forms of the building, situated around the interior courtyards. Pre-Columbian galleries can often feel cluttered, vitrines jammed with a million bits of clay. But the installation design by Geoffrey Pickup lets everything breathe. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

Opened in 1981, the museum contains a rich collection of pre-Columbian works from all over the Americas, though its strengths lie in Chilean and South American art. Seen her, a Moche vessel, in feline form, from northern Peru, crafted circa AD 1-200. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)