The Fixer

- Share via

Willis Edwards had been in some deep holes before, but nothing had prepared him for that moment, late in 1996, when he arrived at the Veterans Administration hospital in Westwood, 130 pounds left on his 6-foot-3 frame, suffering from AIDS.

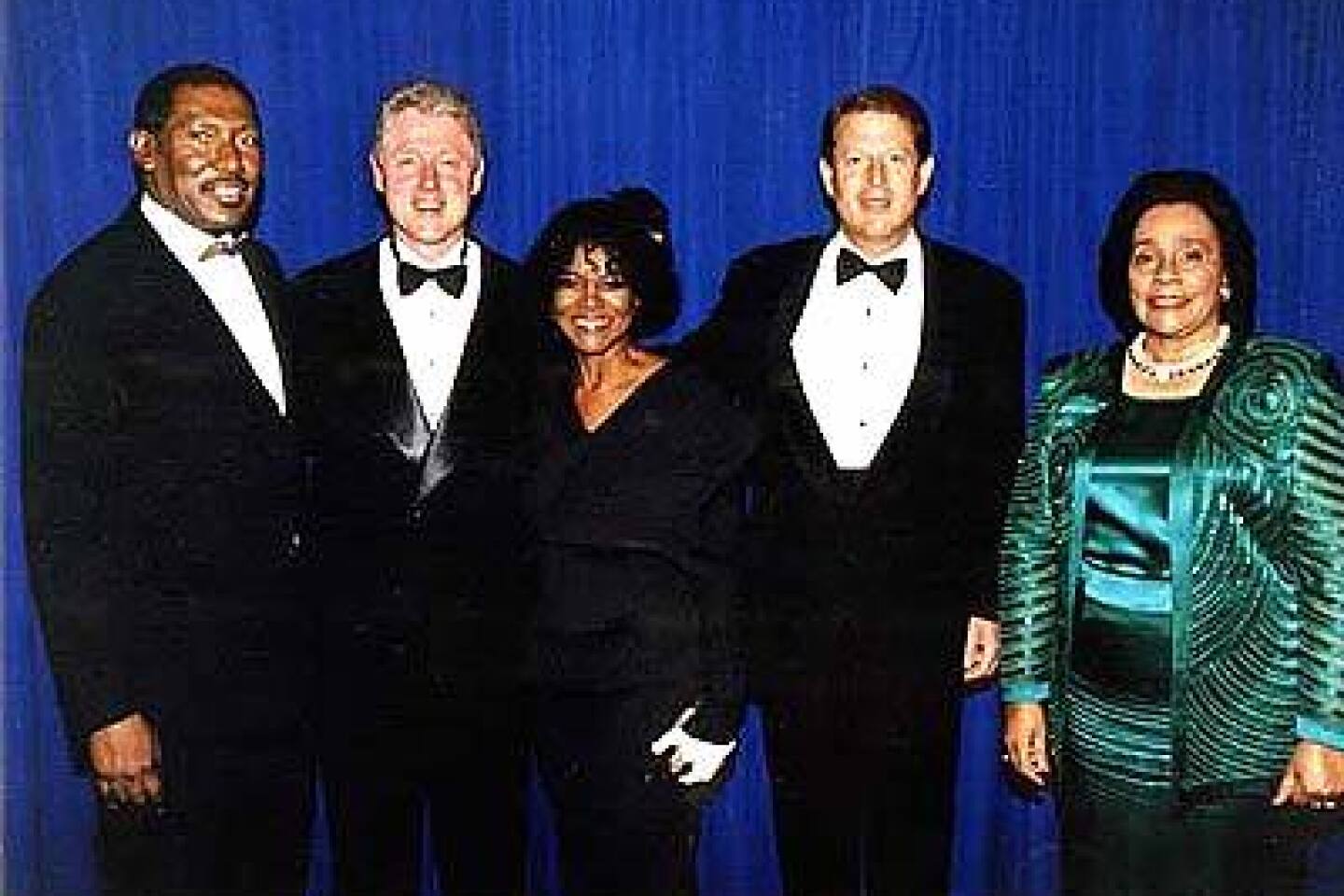

For most of his life, Edwards had been a master manipulator within black power circles. He was an operator--a fixer--with a talent for endearing himself to anyone with clout. He’d talked network executives into making the NAACP’s Image Awards a nationally televised event. He’d been the California advance man on the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s 1988 presidential campaign. He’d smoothed the way for Nelson Mandela’s trip to Los Angeles shortly after the South African anti-apartheid leader’s release from prison.

You couldn’t help but admire Edwards’ brashness. And you couldn’t help but understand the contempt he sometimes generated for his unbridled wheeling and dealing--for being a man who, without wealth or political office or a car or a 9-to-5 job, through raw gifts and sheer guff, insinuated himself into the highest levels of influence.

But now it was gone, all the compulsive deal-making juice, all the confidence. His vast network had dwindled to a handful of friends and relatives who knew about his AIDS and were organizing to help him recover. He staggered weakly from the hospital with his new regimen of drugs. Doctors told him he didn’t have long.

And then, a few weeks later, came a phone call from the mother of the civil rights movement, Rosa Parks, who’d gotten to know Edwards years earlier during one of her frequent winter stays in Los Angeles. Parks stopped by for dinner and prayers as he was convalescing, and shortly after he was asked if he would help Parks raise the profile of her civil-rights institute in Detroit.

The story of what happened next--how Willis Edwards placed 86-year-old Rosa Parks next to Hillary Clinton at the 1999 State of the Union address, where the president praised her lavishly--was a fixer’s crowning moment. Edwards created a buzz that brought Parks the most attention since 1955, when she refused to give up a bus seat to a white man in Montgomery, Ala.

Rosa Parks went to the Oscars, had an audience with the pope and received a Congressional Gold Medal--all orchestrated with Edwards’ help. And he negotiated a six-figure payment to Parks for her life story, which was televised this year.

With his spirits and health bolstered by a new sense of purpose, Edwards captured a regional seat on the NAACP’s national board and became a key player in veteran state lawmaker Diane Watson’s successful bid for Congress last year. He was on a roll, answering the critics who accused him of being out for himself, and telling everyone he knew that despite his fragile health he wasn’t throwing in the towel, just wiping off a little sweat.

“People said I was a goner,” he says. “But sickness is an attitude. I refused to buy into it.”

If Edwards’ life were a TV movie, the music director would be bringing up the stringed instruments about now. But they don’t make TV movies about 56-year-old middlemen, not even ones with coast-to-coast connections. Yes, he’s the guy to call when you need a floor pass on nominating night at the Democratic National Convention or a ticket to a sold-out Patti LaBelle concert at the Greek Theatre. But the perks Edwards dishes out often come at a price. He’s also the guy who, when he spots you in a restaurant, joins your table, surveys the menu and orders the lobster.

Yet you pick up the tab because you feel that, sooner or later, it will pay to know this guy because he knows so many people and he knows how to get a job done, damn the rules.

When I tell Edwards I’m interested in profiling him, my phone starts to ring off the hook. “Willis told me to call and add my two cents to the nice, large and favorable article you’re doing on him,” says one recorded message.

Edwards rattles off a long list of “friends” he’d like me to call: Julian Bond, Johnnie R. Carr, Dorothy Height, C. DeLores Tucker, Sheila Frazier, Beverly Todd, Judy Pace-Flood, Freda Payne, Cicely Tyson, Denise Nicholas, Angela Bassett, Ethel Bradley, Myrlie Evers-Williams, Jesse and Jacqueline Jackson, Bernard and Shirley Kinsey, Brock Peters, Julie Dash, Bill Elkins, Virna Canson, Benjamin Hooks . . .

“Willis, stop!” I say. “This is an article, not your phone book. The story is only going to be so long.”

“How long, brother?”

“Well, it’s not the whole magazine.”

“Bruh-ther,” Edwards says, exasperated, “you must learn how to negotiate.”

Edwards was born in Carthage, Texas, in 1946, and grew up in Palm Springs, but his reputation as a hard-nosed negotiator started in college, at Cal State Los Angeles, where he was active in student government. Edwards was a 22-year-old sophomore when Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968. With money saved up from bagging groceries, he joined a large contingent of mourners that flew to Atlanta for the funeral. He was signed on to Sen. Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign and was among the cheering onlookers at the Ambassador Hotel celebrating Kennedy’s victory in the California primary when the senator was assassinated. The next year, he walked precincts for a city councilman named Tom Bradley, who was defeated in a bitter mayoral race by incumbent Sam Yorty. By that time, Edwards had been drafted and was on a two-week military furlough before heading out to Vietnam. He spent 14 months in Southeast Asia, was wounded slightly in a land-mine explosion and returned home to Los Angeles with a Bronze Star.

Among the Cal State L.A. students who greeted him at the airport was student body president Steve Cooley, later to become L.A. County district attorney. With Cooley’s support, Edwards would be elected the first black student body president in the school’s history. He also became a director of the National Student Lobby and head of its state operation. After graduation, Edwards was hired by USC to be its director of black student services. When Bradley defeated Yorty in 1973, he appointed Edwards to the city’s Social Services Commission.

Edwards quickly developed a habit of turning up in places where he was least expected.

In the early 1970s, Myrlie Evers Williams, activist and widow of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers, flew from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., for a sold-out performance at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. She saw Edwards, a familiar face, wearing a white denim tuxedo with satin lapels. As the crowd of luminaries meandered toward their seats, Edwards took Williams’ arm and shouted commandingly, “Mrs. Medgar Evers coming through!”

“It was like Moses parting the water,” Williams recalls. “I was embarrassed and started rushing through. But Willis had my arm. He slowed me down. He wanted me to pace my walk and just float on through.”

By the time the show started, Willis was gone. He had told Williams he didn’t have a ticket. Yet during intermission, Williams looked around and saw him. “He was in the presidential box. How he got there? I don’t know. But he was there smiling and shaking hands.”

In 1976, Edwards arrived at the Democratic National Convention in New York City, planning to sleep on the floor of a hotel room shared by Diane Watson, then a member of the Los Angeles Unified School District board, and Gwen Moore, then a community college district trustee. He talked his way into a position on the delegate credentials committee and ended up escorting Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis to a meeting with party chairman Robert Strauss and Chicago Mayor Richard Daley. Edwards asked Onassis if she wanted to also meet Bradley, who was being honored at the convention, and she said yes. “The mayor stood up like a little boy, like the queen was summoning him.” Edwards brought him in and then looked around the room at JFK’s widow, Strauss, Bradley and Daley. Willis Edwards was in his glory: the fly on the wall.

Through his work in credentialing, Edwards landed a hotel room and also ended up with some influence over convention seating. He wrangled a limo for Bradley and slipped Watson and Moore into a VIP box next to Onassis and actors Yul Brynner and Lauren Bacall. (“They needed some black faces in that picture,” he rationalized.) From their vantage point on the final nominating night of the convention, Watson and Moore watched as Edwards, who had called in a chit from Bradley, was introduced as L.A.’s youngest commissioner and led the Pledge of Allegiance.

Edwards came home inspired to be more than a fly on the wall. In 1978, he ran for an Assembly seat against Moore and seven other candidates. She defeated Edwards, despite backing from Bradley and the Rev. Jesse Jackson. His effort was marred by rumors that he was gay. (Edwards refuses to answer questions about his sexuality: “It’s nobody’s business.”) But he was about to begin a new chapter.

By 1980 Edwards had been a force in the small Beverly Hills-Hollywood branch of the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People and became interested in the Image Awards, the organization’s annual dinner salute of the entertainment industry. At a time when Hollywood was being criticized for not doing enough to promote and recognize the careers of African Americans, the Image Awards were a valued evening of recognition for the industry--and offered new connections.

When Paramount wanted to gauge black reaction to the movie “White Dog,” a film about a German shepherd trained to attack blacks, it hired Edwards and another man as private consultants. They gave the movie a thumbs-down, and the picture was shelved. The film’s director blasted the studio’s decision, accusing Edwards of acting like a “paid censor.”

In 1982, Edwards became president of the Beverly Hills-Hollywood branch of the NAACP and went on the attack, accusing the movie and TV industries of failing to hire blacks in key positions in front of and behind the cameras. He threatened to call for national boycotts and take action against advertisers. He also sold the first of two taped Image Awards shows for national syndication, a prelude to his goal of a live network telecast.

In 1986, with “The Cosby Show” tops in TV ratings, the NAACP branch decided to honor Bill Cosby with the Medgar Evers Medal of Honor, an award created for the occasion. NBC President Brandon Tartikoff was persuaded to present Cosby with the award at the Beverly Wilshire in front of an audience that included Miles Davis, Cicely Tyson, Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier. When Tartikoff went to the men’s room, Edwards followed. After a brief discussion, Tartikoff agreed to put the Image Awards on NBC. The announcement was made during the show to thunderous applause.

The branch became energized. It swelled with new members recruited by Edwards from USC and local churches in South Los Angeles and artists frustrated over a lack of opportunities. But some longtime members suspected that Edwards was exploiting his unpaid position for personal gain.

“We were volunteers,” says Bob Jones, now vice president of Michael Jackson’s MJJ Productions. “They [Edwards and his allies] were living off the NAACP. I have never known Willis to hold down a job.”

At one Image Awards, Tavis Smiley, then a young aide to Bradley, used his credit card to rent a Lincoln Town Car for Edwards, but Edwards would not turn the car in. “The bill was enormous.” Smiley recalls. “I’m a young kid, not making any money. He eventually made good on it but it tested our relationship.”

Edwards dismisses the episode.

“I don’t understand what the big deal is,” he says. “Tavis was paid.”

Comedian Arsenio Hall went further, condemning Edwards as an “extortionist” and “tennis-shoe pimp” in 1988. Edwards, Hall claimed, had threatened to go public with a complaint that Hall had not hired a sufficient number of blacks to work on his talk show. For a $40,000 contribution to the NAACP, Edwards was willing to remain silent, Hall said. In response, Edwards filed a $10-million defamation lawsuit against Hall. The lawsuit was eventually settled for a substantial sum, Edwards says. Hall would not comment.

Edwards was reelected branch president in 1989, but resigned that same year amid criticism that the branch wasn’t keeping a tight rein on its finances. He was also under fire for taking a $25,000 payment to be co-executive producer for the Image Awards, and the national NAACP took over the ceremony.

Edwards lost his national platform, but that didn’t slow him down. “He has always been someone who comes out of the ashes,” says Sandra Evers-Manly, president of the Black Hollywood Education and Resource Center.

He focused on local issues, such as coordinating Mandela’s visit to Los Angeles, working on Watson’s losing campaign for the Board of Supervisors and operating inside Bradley’s entourage. He put together a video salute to Bradley after he suffered a heart attack and stroke. But he remained bitter about the controversy over the Image Awards. He felt betrayed, both by the national organization and by the branch members who revolted against his leadership.

“I got into my own life,” he says. And then AIDS intruded.

His family, like many of his friends, had watched in silence as his weight decreased, suspecting the worst. Now Edwards was forced to tell people he had “the virus,” to admit that he needed help with transportation, housing, food and medication. He was staying with a friend in View Park, one of Los Angeles’ wealthiest black neighborhoods, in early 1997, when he learned that Rosa Parks was going to visit.

Willis Edwards was 9 when Rosa Parks’ simple act of civil disobedience rocked the nation and captured his childhood imagination. He first met her in 1980, when he escorted her at the Image Awards where she was honored. “Rosa Parks stands for something,” he says. “Children write stories about her. I’ve walked in a room, a restaurant with her and watched. People start whispering: ‘Rosa Parks is here! Rosa Parks is here!’ And they start clapping.”

And now she was going to visit him. “I got on the phone and started calling people. ‘Rosa Parks is coming to my house!’ There is a network of people and if you call them, you know the word will spread around the city.” The visit lasted three hours.

Edwards regained some of his strength throughout the year. By 1998 he was back in step, organizing events for Parks. A week before the Oscars, with the help of a high school friend who was coordinating red carpet arrivals at the event, Edwards scored seventh-row seats and a police motorcade for Rosa Parks, approved by then-Police Chief Bernard Parks. She walked down the red carpet with Edwards on her arm.

Edwards was looking healthier than many people had seen him in a long time. He was eating well and walking every day in Griffith Park. It was on one of his early morning walks that Edwards imagined Rosa Parks in the gallery--in the first lady’s box--when President Clinton delivered the 1999 State of the Union speech. The political calculation was easy: Clinton, immensely popular with blacks and facing impeachment, was likely to welcome the public relations glow from Parks. Edwards called the White House and got nowhere. So he employed elemental leverage: He called the staff of House Republican Leader Dennis Hastert (R-Ill), who said that Hastert would be more than happy to seat Parks in the speaker’s box with his wife, Jean. That accomplished, Edwards called a friend over in the White House. Do you know Dennis Hastert has agreed to seat Rosa Parks in his box? “I’ll get back to you,” was the reply. Within minutes, Edwards had secured a seat next to Hillary Clinton.

“We know it’s been a long journey,” Clinton told Congress in his speech as he described an initiative to bridge the racial divide. “For some it goes back to before the beginning of our republic, for others back since the Civil War, for others throughout the 20th century. But for most of us alive today, in a very real sense this journey began 43 years ago when a woman named Rosa Parks sat down on a bus in Alabama and wouldn’t get up. She’s sitting down with the first lady tonight, and she may get up or not as she chooses. We thank her.” It was the loudest applause of the night, and Edwards felt vindicated. Only now, he told himself, did the initially resistant Clinton staff members get it.

Edwards “could see the picture, the image and the power of the image,” says Minyon Moore, then the political director at the White House. “Once he has that idea and image in his head, you can forget it. It will become a reality.”

The speech made other things possible. Parks flew to St. Louis to meet with Pope John Paul II. And Rep. Julia Carson (D-Indiana) nominated her for a Congressional Gold Medal, which required two-thirds approval of Congress.

Tavis Smiley, by now a contributor to a nationally syndicated black-oriented radio network in 100 U.S. markets, got a call from Edwards. “Brother, I have a little project for you,” Edwards said. Smiley agreed to broadcast the names of those who had not signed the legislation. Within weeks there were more than enough signatures to place Parks among the select group receiving the highest award bestowed by the U.S. government.

Hundreds gathered in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol in June in 1999 as Clinton, top lawmakers and civil rights leaders honored Parks with a congressional medal designed by African American artist Artis Lane--a Willis touch. That same year, she received an honorary doctoral degree from USC. When Parks needed a place to stay in Washington, D.C., Edwards arranged for her to check in at the Mansion on O Street, a luxury hotel. “I’ll put her up free for life,” H.H. Leonard, the owner, told Edwards. In 2000, Parks’ institute obtained more than $1 million in federal and private donations, the largest amount it has garnered in a single year. And Troy State University Montgomery’s Rosa Parks Library Museum opened up on the site of the Empire Theater--at the same spot where Parks was arrested on that bus in 1955. Meanwhile, “The Rosa Parks Story,” a television movie that aired in February, began preparation, with Edwards as executive producer.

The surge of energy Edwards experienced from working with Parks soon pushed him back to the NAACP. He was elected to the national board in 1999 and two years later encouraged the national civil rights organization to have its annual board meeting in Los Angeles, the first time in its 93-year history. He was appointed by Chairman Julian Bond to the committee that oversees the Image Awards. He was also the parliamentarian of the NAACP’s convention in Houston this past July.

At last year’s convention in New Orleans, Edwards spoke about the hardships of living with HIV.

“The NAACP, after initially not having the best attitude [about AIDS], has overcome that, and to a large extent we have Willis to thank for that,” Bond says. “Here is a functioning person whom we know.”

But Edwards is not always an easy person to know. “He lives on his wits and flashes of brilliance,” says Watson. “Willis is that pilot light that sparks the fire that cooks the food.”

He was an early spark in her decision to run for the congressional seat left vacant by the death of Julian Dixon. She was U.S. Ambassador to Micronesia when Edwards called, urging her to run and then becoming instrumental in her campaign’s fund-raising. (He receives a percentage of the funds he raises.) “He has a gift of making the deal,” she says.

Still, Watson did not offer Edwards a congressional staff job after her victory.

“You can’t say, ‘Willis, go do this and that and bring back a report,’ ” she says. “He’s too compulsive. He works for the moment.” She describes her longtime friend as a free spirit who wouldn’t work well in a structured environment.

After walking six miles in the hills of Griffith Park, Edwards sits down one morning to breakfast: oatmeal, eggs (easy over), toast, peaches, hash browns, milk, orange juice and coffee. The medication makes it difficult to taste the food he is eating, but he has to eat a heavy meal to maintain his weight. He’s been told he has diabetes. He has good days and bad days.

He’s trying to interest the mother of Emmet Till, the teenager whose death at the hands of racists in Mississippi was another major civil rights outrage of 1955, in a movie deal. He worries about his 87-year-old mother’s comfort and the future for his nieces and nephews. He’d like to buy a car and move out of his two-bedroom apartment and into a house. He’s mulling whether to write his autobiography.

Interesting. What would the Edwards’ legacy be? I ask. For once his tongue freezes. He offers the legacies of others, of unsung heroes in Los Angeles, people such as the late Rev. Thomas Kilgore of Second Baptist Church, and South-Central social activists such as Mary Henry and Lillian Mobley. But not his.

“It’s something I have to think about,” he says. “Give me 20 minutes.”

“No, Willis,” I say. “You like to negotiate. Let’s negotiate your legacy.”

“I can’t define my legacy to you,” he says. “It’s better for others to say.”

I realize that a middleman has no legacy without the people whose lives he travels between. The legacy of a middleman is: He loved the game. He loved getting people on the outside inside the door. He liked to make sure the people he admired got invited to dinner. And he always made sure he had a good seat.

John L. Mitchell is a Times staff writer whose last article for the magazine was an interview with Rodney King.