- Share via

This story is part of Image’s May issue, which journeys through environments that encourage, nurture or require stillness.

We’re in matching pajamas — burgundy, orange, brown — spread like starfish across the heated floor. We’re in the jimjilbang, roughly translated from Korean as “heated rooms for steaming and relaxation.” Some whisper, some sleep, some stare at the ceiling, lost in thought. The pink Himalayan salt sauna glows like stained glass. I taste the salt of my own sweat gathering on my upper lip. Everything moves at half-speed. I’m here to clear mental space, like closing tabs on my phone, making room for deeper processing.

I bring big questions and big feelings to the spa, letting them work out during the rituals of bathing. I rinse off the outside world upon entry and unwind in the hot tub. The heat is a litmus test of where my mental edges are at — how long I need to return to my body after the week’s stresses. Icy cold plunges reset my nervous system — like a computer reboot — reminding me to release with every breath. I rinse and repeat, these waters providing me with safety and comfort on my path for good orderly direction.

For years, I’ve been touring spas not only in the U.S. but globally, including Japan, Denmark, Paris and Mexico. Inadvertently, I’ve become bathing-obsessed (like getting-married-at-a-hot-spring obsessed), writing my observations on a Substack named S.P.A., paying tribute to the ancient Romans who used the abbreviation to mark the presence of water — most commonly thought to stand for either Salus per Aquam (health through water) or Sanus per Aquam (sanity through water). I explore “Why not both?’” since water cleanses us — not just physically but spiritually, emotionally and mentally.

Los Angeles stands out as one of the most vast and varied bathing cities in the world. Across the city, there are dozens of Korean spas, Russian Jewish banyas and even natural hot springs hiding inside nondescript buildings and strip malls. The history of L.A.’s bathing landscape runs deep, and there is more than what meets the eye today. During the late 1800s, settlers in Los Angeles searching for gold or oil instead found water (not quite the fountain of youth but not not the fountain of youth either). Massive public swimming pools, known as “plunges,” were scattered across the city where people would learn to swim. Bimini Baths, once one of the largest, stood at the present-day intersection of Third Street and Vermont Avenue, where a Vons grocery store now sits.

One relic from this era is the Beverly Hot Springs, an artesian well once used by Native Americans that was rediscovered in 1910 when Richard S. Grant purchased the land as a wheat field. Over time, the well was forgotten, until 1984, when it was rediscovered and turned into a spa. The alkaline water with rich mineral composition is the only natural hot spring that flows directly into a building left uncapped in central Los Angeles. The walls mimic a cave and the water echoes against the bouldered ceiling. When I go, I wear a disposable hair net and pretend I’m a grotto nymph, crawling around the corners of my subconscious transporting me back in time.

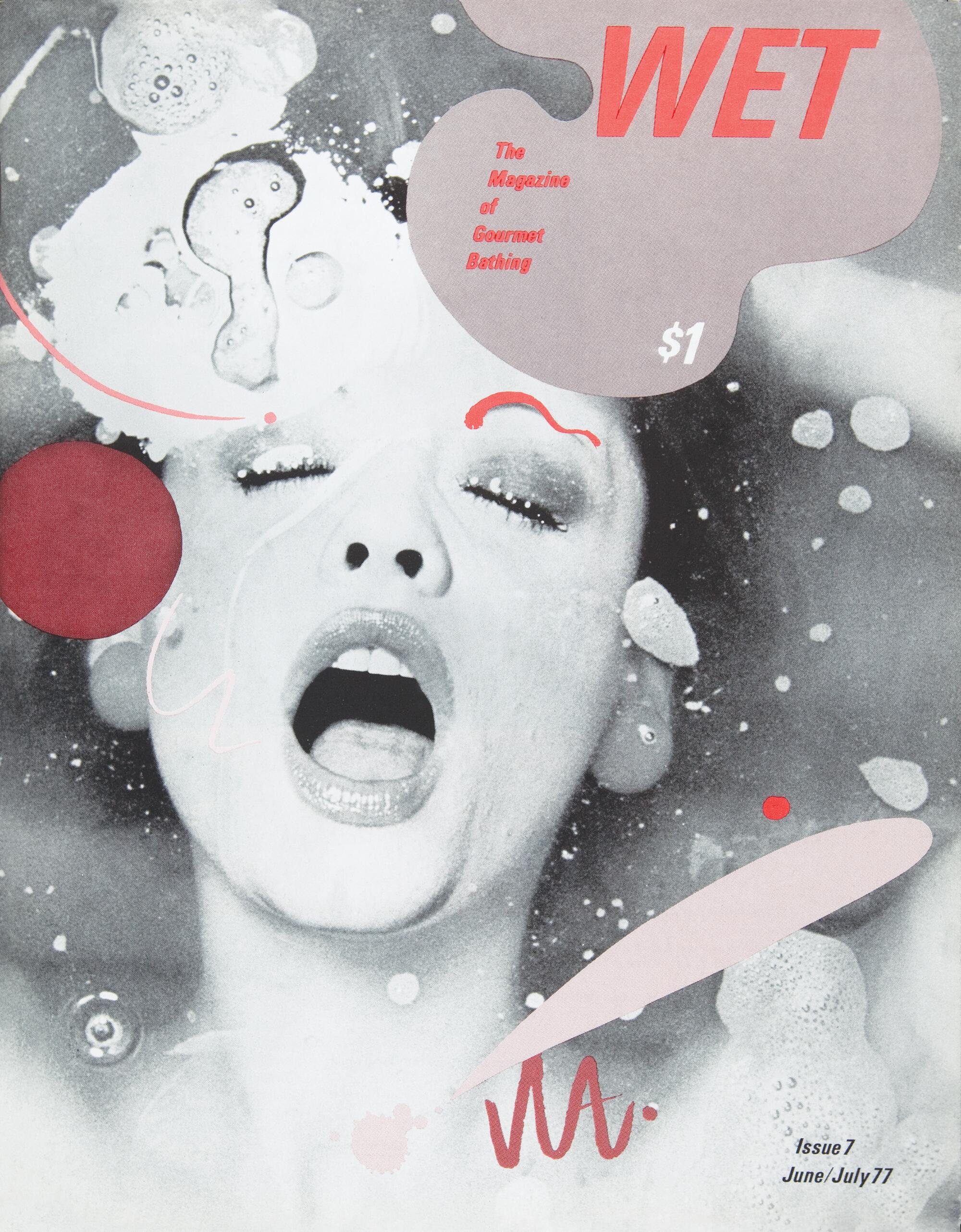

One of the earliest establishments I visited in L.A. was City Spa, a Russian bathhouse that has been operating for more than 70 years. It was here that my journey into bathing culture intersected with the pioneering work of Leonard Koren, who began documenting L.A. bathing culture back in 1976 with Wet: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing. A visit to City Spa confirmed my suspicion: This cherished Eastern European-style establishment was formerly Pico-Burnside Baths, once the stage for Koren’s artful magazine photo shoots.

Wet, which ran for 5½ years, was a glorious celebration of bathing and featured contributions from figures like Richard Gere, David Lynch, Debbie Harry and Ed Ruscha. The issue themes were playful, ranging from “Drinking Water: Bathing From the Inside Out” to “Getting Wet in Public Places” (you can peruse the back issues in the LACMA archives). The idea for the magazine came to Koren while he was in architecture school at UCLA. Disenchanted with modern and more “heroic architectures” of his day, he “became more curious about less self-conscious, more human approaches to place-making” — like the everyday space of bathrooms. The 34 issues that followed were odes to the “small, intimate environments” of bathing, and were the beginnings of Koren’s long career in publishing, as he went on to make celebrated books about raking leaves, arranging objects, Japanese fashion and more.

Curious to talk with Koren about all things bathing and Wet, I set up a call to connect with him in Rome, where he now lives.

Courtney Wittich: In your early 20s, you co-founded the Los Angeles Fine Arts Squad, a collective that made murals around the city in the ’70s, and then you pursued a master’s degree in architecture at UCLA. What pulled you toward bathing as a creative focus?

Leonard Koren: While in architecture school, I fantasized about creating a widely accessible environment that offered some of the same aesthetic wonder and intimacy as the traditional Japanese tea house did. The American bathroom, I ultimately realized, was in lots of ways a contemporary solution. This led me to further explore the silly and sacred dimensions of baths and bathing.

CW: The first bathing event you hosted was at Pico-Burnside Baths, which led you to the creation of Wet magazine. Can you tell me a bit more about that?

LK: I had been doing what I called “Bath Art” projects. I did silkscreen prints and lithographic prints of people bathing in various substances and various modes. There were quite a few people who had modeled for my projects, mainly friends and acquaintances, designers, people in the movie industry. And I realized that I really should repay them for their kindness. I had very little money at the time and realized that if I sent everyone $5 it wouldn’t be very meaningful to them. Then, when I was talking to a friend, he reminded me that I knew this place — the Pico Burnside Baths, which was an old Russian Jewish bathhouse. I made an appointment to talk to the owners, and I asked them if I could rent the bathhouse for the evening, and they said, “Well, we don’t do that.” After talking for a while, they said, “OK” (I believe it was $450 for the night). I said we’re going to have men and women here, and they said, “No, no, there’s never any coed bathing here.” And I said OK, and as I was walking out the door they said, “If you’re out by midnight.” And that was basically it.

I asked some friends to cater, who were great cooks. I hired an electric violinist to rove around the bathhouse and play during the event. People came in every manner of dress and undress because the invitations I sent out were purposefully vague. My theory was that people didn’t know how they should dress or how one behaves when a person, fully clothed, is talking to a nude person. New social rules were invented on the spot, creating a lot of what I call social energy. It was a very electric evening — people like Rudi Gernreich, the inventor of the modern one-piece bathing suit, and even a reporter from the L.A. Times, Beth Ann Krier; there was an article of this bath party on the front page of one of the sections of the L.A. Times. I was excited it was a very successful event, and in the following days, I thought about how I could harness this social energy. Out of that rumination came the idea to start a magazine about gourmet bathing, which I called Wet!

CW: Did this bathing event become the template for the magazine’s future events?

LK: It’s difficult to say. The bathing events of Wet were conceived as artistic social experiments, not as business prototypes. The rituals and social understandings that evolved out of the Wet bath parties were fluid, ever-changing and unpredictable. I would think that the magic of spontaneity and extemporaneous invention is something that the current bathing businesses hope for.

CW: Each issue of Wet had such a unique visual identity via the logo, layout and cover art. How did you approach the design for each issue? What influenced your choices?

LK: Wet was above all an art project. A key aspect of the project was to make each new issue of Wet as conceptually and visually different from the previous ones as possible. So all the design and editorial decisions naturally evolved from this self-imposed mandate.

CW: You were creating this whole world around bathing — events, bath art, papers, a magazine. Wet was so ahead of its time in how it blended design, philosophy and culture. Did you think of it as part of a larger cultural shift? What were you consciously responding to — or rebelling against — when you made it?

LK: I came up with the idea for Wet when living in Venice, California, in what had once been a gondola garage. At the time Venice had a tremendous amount of creative freedom because no one really cared much about what went on there. I think Wet was simply my artistic response to the absurdities inherent in being a human being at that particular time and place.

CW: While living in L.A., did you have favorite places to bathe? Any spas or springs you kept returning to?

LK: On weekends while in architecture school and while making Wet, friends and I would travel up and down California looking for obscure, undeveloped hot springs. Of the developed hot springs we found, Esalen and Tassajara, circa 1976, were my favorites.

CW: You’ve lived in California, Italy, Japan. What have you learned from each place about bathing and bathing culture?

LK: In California, I learned that nature is benevolent and magnanimous. For example, nature provides hot springs that bubble up with the perfect bathing temperature in unbelievably beautiful places. In Japan, I learned that close attention to the ways of nature can lead to enhanced levels of sensory experience. And in Italy, I learned that the extremely high level of bathing culture circa 200 C.E. has completely disappeared.

CW: These days, spas and bathhouses have become an escape from digital life. Back in the ’70s, people didn’t have phones glued to their hands. Was there anything people were trying to get away from then? Has the role or function of the spa changed because of modern technology?

LK: I think life in L.A. always had its uniquely absurd dimensions. And bathing in its myriad forms has always been a way of reveling in these absurdities — and as a way of transcending them.

Courtney Wittich is on-the-clock fashion PR, off-the-clock sauna sommelier, bathing connoisseur and water gourmand. Find her soaking it in and sweating it out.

Words Courtney Wittich

Photography Taylor Washington

Styling Autumn Lovelace

Art direction Jessica de Jesus

Models Madelane De Jesus, Cecilia Alvarez Blackwell

Makeup Paloma Alcantar

Hair Kessia Randolph

Fashion director at large Keyla Marquez

Production Cecilia Alvarez Blackwell

Photo assistant Nanichi Oliva

Styling assistant Luna Curry

Location Beverly Hot Springs