Some tough choices — and pushback — along the proposed bullet train route

- Share via

Urban neighborhoods, protected wetlands, olive orchards, a federal reservoir and a few sleepy towns will go by the passenger windows of the first California bullet train when it pulls out of San Jose on its way to the Central Valley.

But before that inaugural journey planned for 2025, state officials — already facing financing and technical challenges — will have to deal with opposition from land owners and expensive mitigation demands from others along the way.

The bullet train’s exact route will not be set until environmental impact reports are issued, scheduled for next year. Still, the 30-mile stretch from downtown San Jose to Gilroy is a microcosm of the problems the California High-Speed Rail Authority has encountered up and down the state.

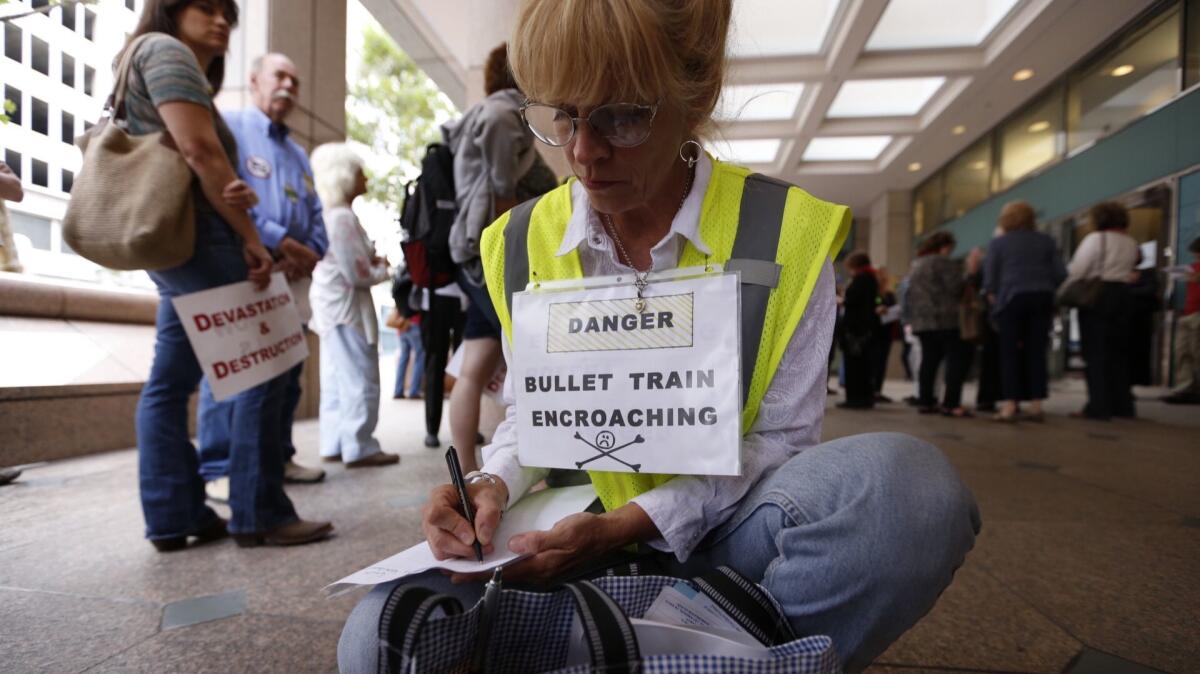

Over the last half-dozen years, the project has been bombarded by a dozen lawsuits and sharp protests — including a 2015 demonstration that drew hundreds to a downtown Los Angeles rail authority board meeting. The pushback has caused extended delays and led to costly political compromises.

Officials have said they are mindful of the project’s impacts and have tried to minimize them, but they have a railroad to build. In lengthy remarks in 2015, rail authority Chairman Dan Richard cited the larger benefits of the bullet train and lamented the effects, adding: “It just comes with the territory.”

In the low-income communities in south San Jose, residents are objecting to the bullet train’s path, arguing that their area long has been sliced and diced by freeways.

“I risked my life to buy this house,” said Jeremy Taylor, a Marine who fought in Afghanistan and has been trying to organize neighbors in his Gardner neighborhood. “They are going to have to rip it from my hands to take it away.”

According to rail authority spokeswoman Lisa Marie Alley, the state is considering building an elevated viaduct to reduce the amount of private property that will have to be acquired along the route to create a right of way.

“They are trying to thread the needle,” said Pierluigi Oliverio, who represented the area for a decade on the San Jose City Council. “There are a lot of disgruntled voices.”

As the train leaves urban San Jose, heading south along Monterey Highway, it will go by the Coyote Valley and Soap Lake open spaces.

This summer, the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority requested that rail officials construct viaducts that would allow wild animals a migration path from the Diablo Range to the Santa Cruz Mountains. The cost of such viaducts, if approved, could be millions, depending on their lengths.

“We have spent $3.5 billion in conservation investments in these two mountain ranges,” said Andrea Mackenzie, the agency’s general manager. “These are the last remaining open lands of the Silicon Valley.”

And the small, unincorporated area of San Martin is fighting a plan to locate the rail line along its main highway, arguing it would destroy the rural character. Trina Hineser, who heads an alliance of 500 households, said the community largely had been largely left out of planning until February, when the state held an outreach meeting.

Jeff Martin, an olive oil rancher in the area, said he could lose his entire 30-acre grove and new milling plant if the state decides it needs his land. “I voted for high-speed rail and I found out it is all smoke and mirrors,” he said. “This project puts hundreds and hundreds of people like me in limbo.”

The rail authority still is weighing the route through the city of Gilroy, which bills itself as the garlic capital of the world. One plan would cut through the historic downtown; another would run along undeveloped land to the east.

Some environmentalists want to protect the open land, while some residents want to preserve their main street.

“It’s a mess,” said Gary Walton, who heads a downtown business group. “You can’t pin down the rail people on anything. They tell you what you want to hear. They say they will get back to you, but they never do.”

Joseph Thompson, a Gilroy attorney, said a state proposal for high sound barriers on the rail route will leave the city looking “like it has a Berlin Wall.”

Critics also argue that the bullet train would accelerate sprawl in the Central Valley. A recent report by Spur, a nonprofit San Francisco urban planning advocacy group, said that local governments along the route do not have the planning experience and use controls needed to prevent development from eating up farm land and exacerbating environmental problems.

However, the northernmost portion of the 240-mile starter system from San Jose to south of Wasco also shows the potential of what a bullet train could mean for the economy.

The project got a big boost this year when Google announced plans to build a new campus in San Jose, right next to the future high-speed rail station. The 30,000 employees who might be based there would need housing. Those willing to take the train to Gilroy, Fresno or Merced would have lower-cost options.

Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-San Jose) said her support for the project was undiminished by the difficulties ahead.

“Building big things is not easy,” she said.

Follow me on Twitter @rvartabedian

ALSO

Another key California bullet train executive is leaving

California bullet train costs up $1.7 billion for Central Valley segment

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.