Great Read: Fancy feathers rule at pigeon fans’ competition

- Share via

Mike Tyson slips off his black leather jacket and takes a white homing pigeon from Luthor Nelson’s hands. The former boxer — and pigeon fancier — easily tosses it up with one hand. Then he helps open four wooden crates that hold 99 more of the birds.

The birds stream out and up, just barely clearing the people standing nearby. The air vibrates under the pressure of 198 white wings. The pigeons make a circle over the parking lot, then fly behind the Ontario Convention Center.

They look like white doves as they circle in front of the sun. But using doves would be a disaster, Nelson says.

“You’d be embarrassed,” says Nelson, who releases the birds for funerals, weddings and special events like this one, the premier annual event on the pigeon circuit: the National Pigeon Assn.’s Grand National.”They would land on you. They would poop on you. Hawks would come down and grab them right in front of us.”

And, Nelson says, you would never see them again.

When he releases his pigeons, they fly to his home in Hacienda Heights, following the 60 Freeway for about a mile on the way. He points to photos that show several white birds flying with traffic at about 55 miles per hour just feet off the ground.

“I’ve often thought that if some guy’s going, ‘God, would you just give me a sign? Should I marry her or shouldn’t I?’

“All of a sudden, BAM! White flocks. ‘God, wow, you are amazing. What a sign!’”

The common street pigeon is packed with recessive traits that can produce more than 500 different breeds within the same species. Every year, the Grand National pigeon show brings together thousands of these birds and their owners to compete.

In front of the convention center, Tyson is the celebrity draw of the Grand National, but he’s also excited to be here. “This is my Super Bowl,” he says.

He’s kept pigeons since he was a kid growing up in tough neighborhoods in New York.

“Where I come from ... the toughest guy normally has beautiful birds,” he says.

“Automatically they know they have a relationship with human beings. Anything can kill them. But they depend on us to take care of them.”

One day, he says, a neighborhood kid killed one of his birds right in front of him. And then he had his first fight.

::

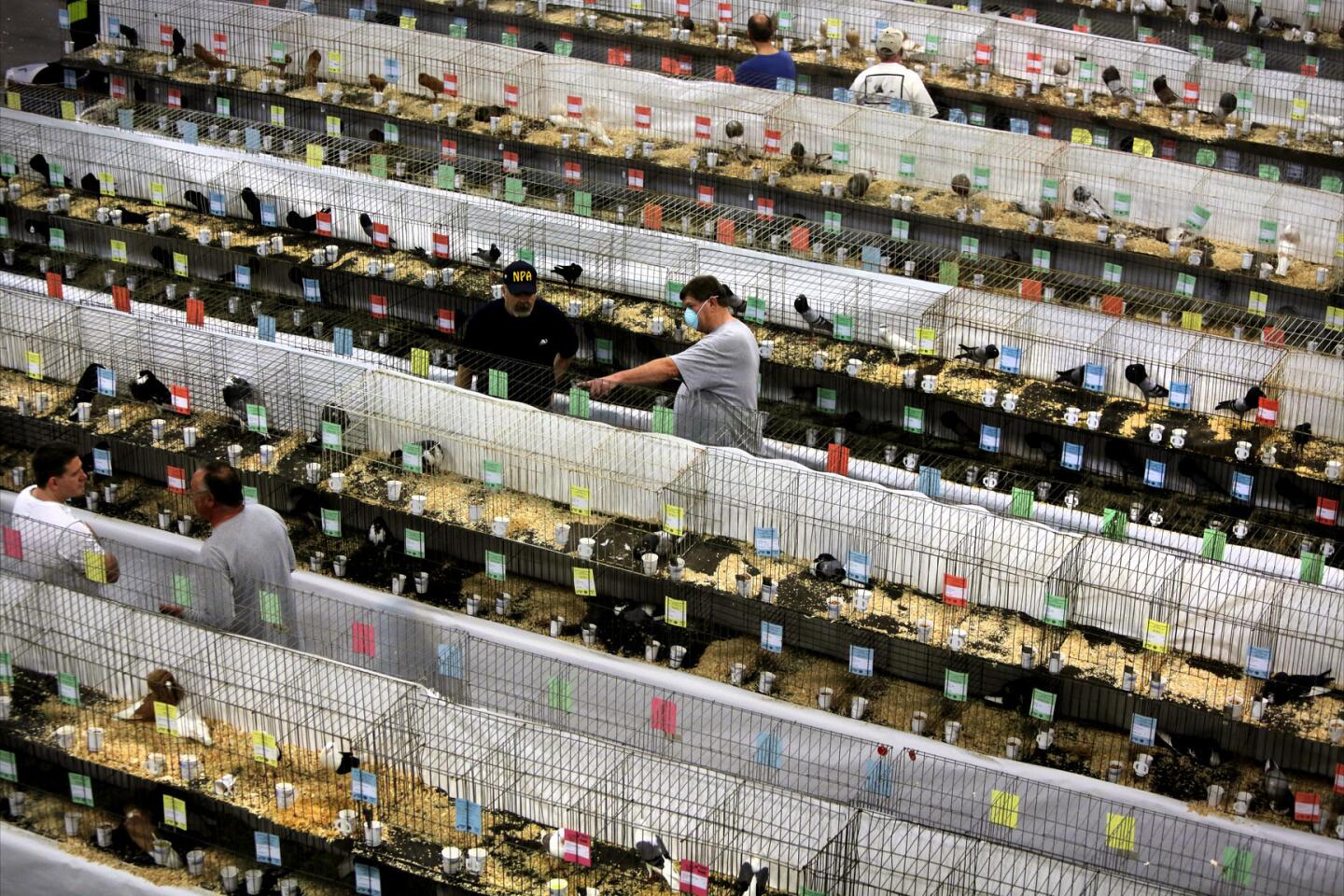

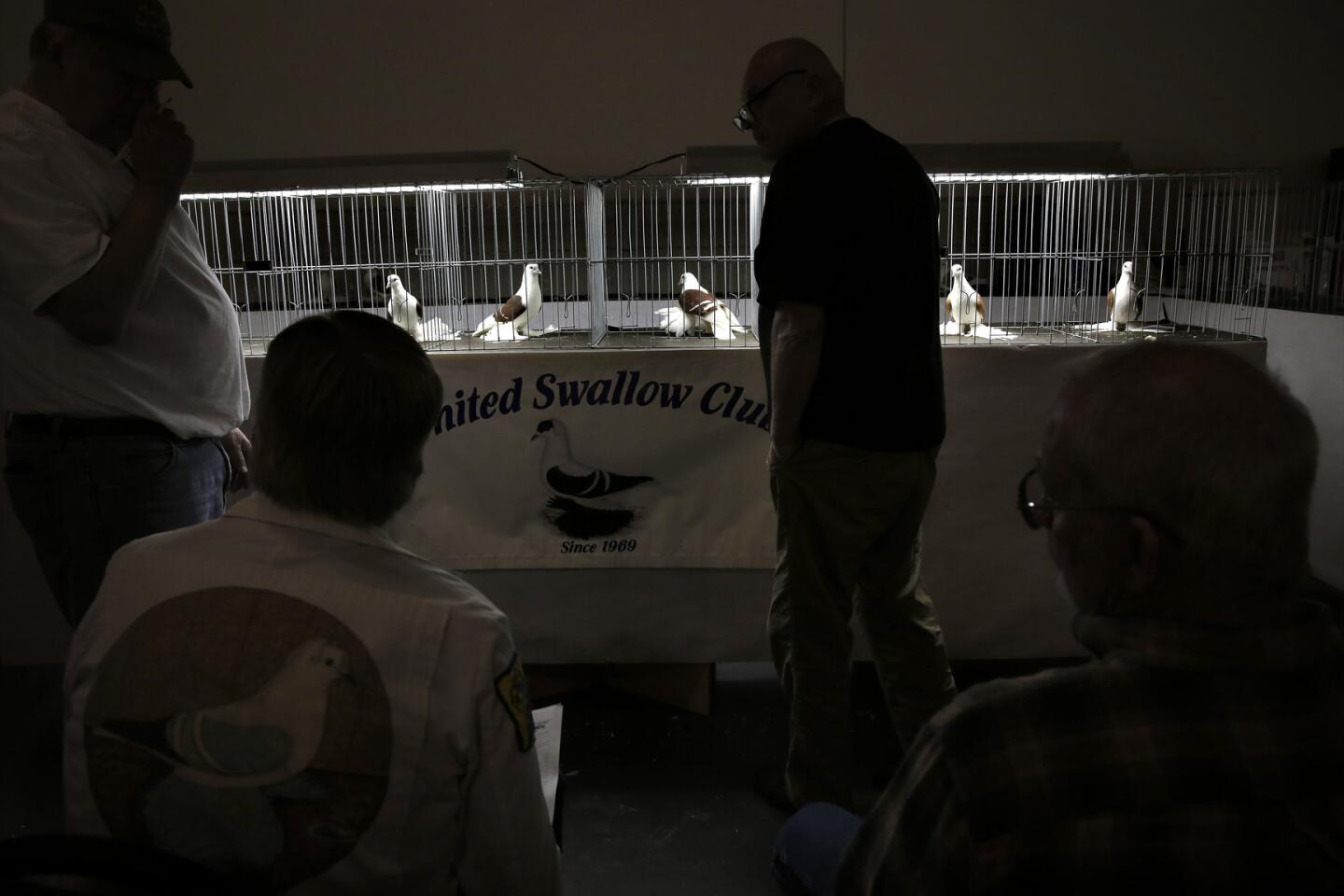

The Grand National is the pigeon world’s version of the Westminster dog show. More than 7,800 “fancy” pigeons were on display over three days last weekend.

As at the famous dog show, top bird breeds are brought and judged by each breed’s standard. The top competitors from each breed are then judged to determine a champion of the entire show.

The birds are the same species as the pigeons you can find on a downtown street, but fancy pigeons have been bred for specific characteristics over hundreds of years.

Where I come from ... the toughest guy normally has beautiful birds.

— Mike Tyson

There are hundreds of breeds, each with a distinctive look. Fantails look like little sumo-wrestling turkeys. Large feathers sprout from their tail and fan out, as the name implies. They tuck their heads back behind their breasts and bounce from foot to foot like proud warriors.

King pigeons look like small, mean chickens. Their bodies are white, but their eyes, seemingly squinted in rage, are black. Instead of scampering away from the edge of the cage as other breeds do, they dare a person to get close.

The breeders are from all over the world. Several judges come from Europe and Canada. A mechanic traveled 36 hours from South Africa to see the show. Most are men, and most are older.

Bob Smith might be the oldest pigeon fancier here. A World War II vet who trained pigeons for missions during the war, the 97-year-old sits in a wheelchair, showing off bright blue socks. He’s wrapped in a brown tweed suit jacket and topped with a matching tweed cap. He’s hanging out with the “tumbler guys.”

The birds come in many colors and have been bred for their ability to somersault during flight.

Smith fears pigeon fanciers are a dying breed.

“Kids have too much else to do today,” he says. “They don’t have time for pigeons.”

::

Melissa Ferrell, one of the few top female breeders, strokes the feathers around the face of one of her Jacobin pigeons and massages the back of its head, then places it back in its cage. The judge sits nearby with his back to the birds and breeders so that he won’t know who owns which birds.

It’s just after noon on the final day of the Grand National, and Ferrell has four Jacobins competing against eight other finalists for national champion. The judge is called to inspect the birds. Jacobins wear their feathers like 1920s movie stars, fluffy and tall like a high-collared coat. You can’t see their heads, which are hidden by even more feathers stretched high.

Two guys from Saudi Arabia wait nearby. They’ve expressed interest in buying Ferrell’s birds and are eager to learn the winner.

About 50 people watch the judging process. Some have phones out, recording. One breeder, a hairdresser from Dallas, points at one of Ferrell’s birds. “That’s a big contender,” he says.

Ferrell’s lips are pursed in a thin line, and she’s gripping her hands tightly behind her back.

“I have no chance in hell,” she says.

Ferrell, 44, has spent months preparing her stock.

“I’ve been working the last two months out there every weekend giving baths and cleaning toenails,” she says. “And it’s over in two days.”

She was born into the sport. Her dad was a well-known breeder.

As kids, Ferrell and her brothers would go with their dad to the national shows.

“We would just sit and color all day long,” she says. “We never went on vacation.”

Ferrell avoided pigeons as an adult, until one day about 12 years ago when her father called from his home in San Bernardino County. A wildfire was racing toward his house and his birds. He needed help.

They took the birds back to Ferrell’s house in Tulare, which was the family’s old house. When the fire cleared and her dad rebuilt, he came back for his birds. He left Ferrell two, and from that couple, she’s been breeding highly sought-after birds.

Jacobins can fetch from $25 to several hundred dollars. But champions can sell for thousands.

::

Another breeder in contention, Drew Lobenstein, gets in position with a camera at the ready. He’s wearing a long white lab coat. He’s been preparing his birds for years. He wants a champion.

Lobenstein, 68, has about a thousand birds on his half-acre plot in Reseda.

He got his first pigeons when he was 6. His dad brought home several pigeons, intending to raise them in their yard and then eat them for supper.

Drew was in tears at the dinner table when the cooked squab was brought out.

“It was a scene,” Lobenstein recalls. “My father says, ‘Ah! We’re not going to do this anymore. Enough of that.’”

From then on, the pigeons were Lobenstein’s to take care of, and he’s owned pigeons ever since.

A few years later, Lobenstein fell in with the pigeon people at the Los Angeles Pigeon Club, which has been active for more than 100 years.

There he met a family, the Atwoods, who invited Lobenstein to visit their birds and talk pigeons.

“I used to drop by on my way to high school and visit with the grandpa and learn about pigeons,” he says.

The Atwood family willed the house — and a few of the coops — to him about two years ago, and he moved out of an apartment and into the house.

“The best pigeon man in the game was on this property,” he says, pointing at the ground. “And my birds are in his buildings and on this lot. I just get the sense that his influence is here.”

Lobenstein teaches six public-speaking classes split between Moorpark College and Los Angeles City College. And the rest of his time is dedicated to his pigeons.

About a week before the Grand National, workers scurry around his house and yard, remodeling the living room and preparing the yard and pigeons for visitors. The birds coo softly in their coops near an empty oval-shaped swimming pool. A couple of orange cats mill about. They ignore the birds; they’re hunting for mice.

Friends call his yard “genetic Disneyland” for the diversity in the breeds and his stock.

Referring to his flock of about 1,000 pigeons, he says, “I have just as many birds as the zoo might have.”

::

The judge flattens his hand vertically, guiding a Jacobin to stand up straighter. He prods another so he can see it properly from the side. He hands a few birds away and begins to shuffle birds between one of six cages. He’s ordering them, calculating their points in his head.

The judge moves one of Ferrell’s birds to the first cage, a good sign.

He steps back to look at other birds and reorganizes them.

And then he pats the top of the first cage.

“The champion,” he says. The crowd applauds, and Ferrell starts crying. It’s her first national champion.

Her brother moves in for a hug. “Wishing Dad was here,” she says.

The judge, a top Jacobin breeder and cattle rancher, elaborates on his decision. “He has so much wealth of feather, and he carries himself so well. He’s a power host.”

“He’s just a very nice pigeon.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.