Carrying all his possessions, Norman Williams heads to a Palo Alto, Calif., church where he will spend the night. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

Norman Williams, recently released from prison, checks on his clothes in the back of a car owned by Michael Romano, a Stanford law school lecturer who launched the Criminal Defense Clinic. Williams was raised as one of 12 children in a household without a father and with an alcoholic mother who abandoned the children for days at a time. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

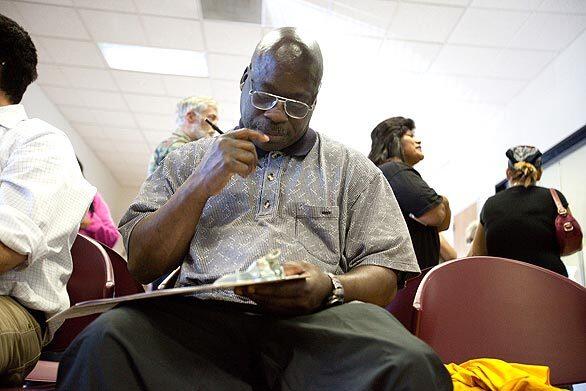

Norman Williams fills out forms for general assistance in San Jose. In court papers, Stanford law students argued that Williams horrific upbringing meant he should be spared a life sentence. They noted that he had never acted violently and was known as gentle and caring to his family, having donated a kidney to an older brother. After more than a decade in prison, he was also free from the grip of drugs. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

Advertisement

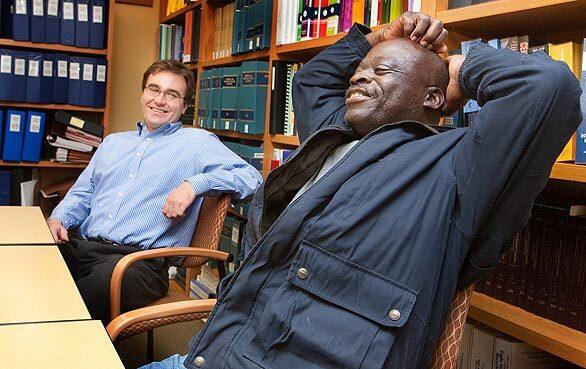

Norman Williams, right, with Mark Melahn, who worked to get the third-strike offender’s 25-years-to-life sentence reduced. Williams had lived most of his adult life either behind bars or on the streets. He earned cash by collecting cans for recycling, but also stole to buy food and drugs. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

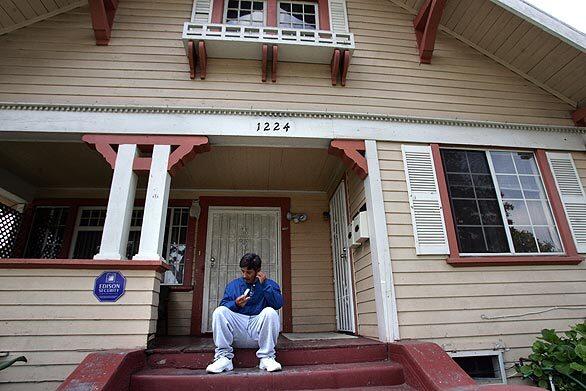

Charles Ramirez listens to a newly purchased CD player at a halfway house in Los Angeles. He got 25 years to life in 1996 for his third strike, stealing a van’s radio. After efforts by Stanford law students, his sentence was reduced to six years and he was released. (Bob Chamberlin / Los Angeles Times)

Charles Ramirez was neglected by his mother and physically abused by his father and his girlfriend. He became homeless and addicted to drugs. Before his third strike, his criminal history constituted mostly drug and theft convictions, including two residential burglaries committed in October 1991. (Bob Chamberlin / Los Angeles Times)

Forty-two-year-old Charles Ramirez at a halfway house in Los Angeles. (Bob Chamberlin / Los Angeles Times)