Gov. Brown reinvents himself as the anti-politician politician

- Share via

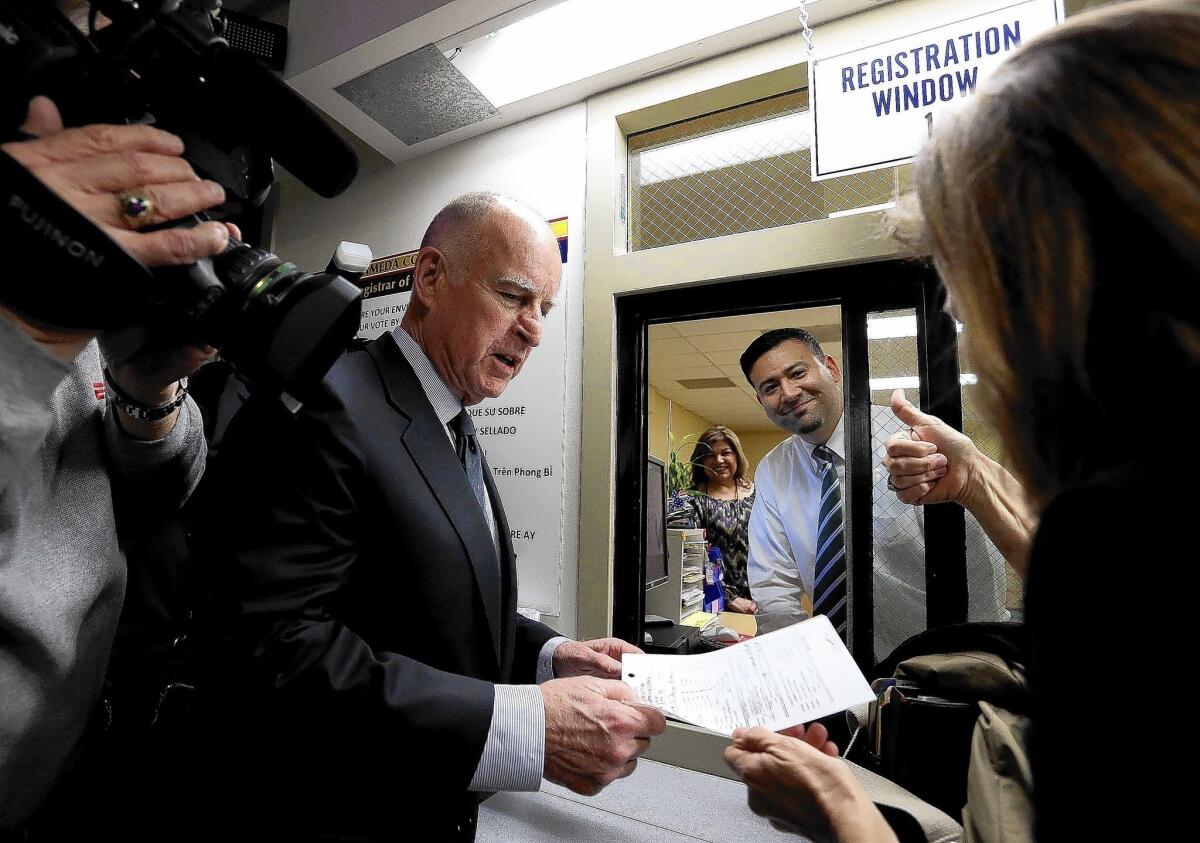

SACRAMENTO — On a recent Thursday morning, Jerry Brown walked unannounced into the basement office of the Alameda County registrar’s office to draw reelection papers. With a post on Twitter and an email to supporters, he then declared his bid for an unprecedented fourth term as California governor.

The moment — low-key, offhand, deliberately anticlimactic — captured the essence of the Democrat’s newest incarnation: Late in life, at age 75 and apparently done seeking higher office, Brown has reinvented himself again, this time as the anti-politician politician.

He shuns most trappings of the office. There’s no motorcade, no entourage. The governor showed up at the elections department with a lone campaign advisor and his wife, who snapped a photo using her smart phone.

Brown fashions many of his own speeches, veto messages and even press releases. His staff in the governor’s office is about half that of his Republican predecessor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, who employed as many as 230.

He often goes months without a public appearance, sometimes holed up at his home in the Oakland hills, calling authors, experts and others he wrings for information — conversations that usually open, “Hello, this is Jerry Brown. Do you have a minute?”

It is as though Brown wants to run the most populous state in the nation more or less by himself, tackling matters large (California’s budget) and small (picking a poem to mark Arbor Day) with the same degree of supreme confidence and minimal public display.

“A lot of organizations quickly take on extra layers and unnecessary procedures ... just to carry on the business,” Brown said in an interview. “We’re leaner, and I think more coherent as a result.”

Brown being Brown, there are the usual idiosyncrasies.

For three days last summer, as the federal government hurtled toward a shutdown, the governor checked out to attend a conference in Oakland on the ideas of the late social critic Ivan Illich, opening the session by noting the two met in the 1970s at Green Gulch, a Zen monastery in Marin County.

llich, who had been a Jesuit priest, railed against institutionalized education, the prevalence of automobiles and modern medicine — or, as the Jesuit-educated Brown put it that day, challenged “the certitudes of modernity.”

For Brown, a spokesman said, the getaway was “the equivalent of you or I going to a baseball game.”

The conspicuously inconspicuous approach may be at odds with today’s culture of rapid-fire tweets, blogging and around-the-clock news coverage. Other governors huddle with tacticians who stage-manage their public appearances, focus-group their statements and work to shoehorn them into every passing news event.

But ever since his last unsuccessful presidential bid, in 1992, Brown has shown an acute sense of political timing, serving as his own strategist and methodically climbing back to political power one elected post — Oakland mayor, state attorney general, governor — after another. (He has ruled out — reluctantly — a fourth try for the White House in 2016.)

“Going dark is not a strategy I would recommend for 99.9% of other politicians,” said Steve Maviglio, who ran Gov. Gray Davis’s press operation and served as spokesman for three California Assembly speakers.

For Brown, though, “if not being in the newspaper or in front of the camera every day is working for him, why mess with success?”

Still, there is no shortage of critics.

Costs have soared for one of Brown’s pet causes, a $68-billion high-speed rail project, and voters have distinctly cooled on the idea. One of Brown’s main GOP rivals for office this year, Neel Kashkari, has made opposition a centerpiece of his campaign.

Another major proposal, a $25-billion project to redistribute water throughout the state, is opposed by environmentalists and others.

Some fellow Democrats, speaking privately to avoid the governor’s ire, say he should do more to address the state’s soaring pension costs, be more daring in overhauling public education and use his high profile to become a leading national voice in the debates over immigration and same-sex marriage.

Brown, though, appears unmoved by those who question his style, practicing an almost improvisational form of governing, without the office structure or hierarchy typical of most governors. “Making it up as he goes along, day-by-day, depending on the nuances,” as one insider put it, speaking anonymously so as not to anger Brown or his wife.

Late into the night, Brown pecks away at his iPhone, conducting his own policy research with a decades’ accumulation of sources, people he sorts by subject. “Jerry puts us in silos, silos of expertise and knowledge,” said Rusty Areias, a former Central Valley lawmaker whom Brown has known since the 1970s and typically consults about water, agriculture and other rural issues.

The governor usually won’t telegraph his thinking, preferring to exhaust a subject with questions and move on to the next phone call.

“He’s constantly synthesizing … foraging for information,” Areias said.

It is not advice that Brown seems to want from those he consults, said Areias and others who speak regularly with the governor, but rather facts and some perspective to help guide his decisions.

A former seminarian and Yale Law School graduate, Brown has never been shy about flaunting his intellect, quoting obscure philosophers and sprinkling his conversation with Latin proverbs. He can be quick to dismiss those who question his judgment or the purity of his convictions.

When the Sacramento Bee raised questions about the construction of the $6.4-billion San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, Brown called the reporters “amateurs” and said their work “border[ed] on malpractice.”

Nine months later, when various defects delayed the bridge opening, the governor told reporters, “I mean, look, [stuff] happens.”

Not surprisingly, some find Brown’s manner off-putting and arrogant. But if he is not warmly regarded in all quarters, he is widely respected, and since returning to the governor’s office in 2011, he has more or less had his way.

California’s finances are on the mend after years of teetering near collapse, thanks to an improving economy but also the tax hike the governor won from voters in an uphill fight. And he has rarely been challenged by the Legislature, even when Democrats had a veto-proof supermajority.

Despite some grumbling, lawmakers have supported most of his major policy initiatives: a shift in school funds from richer to poorer neighborhoods, changes in public pension arrangements, the prison “realignment” program that altered custody rules for felons, elimination of redevelopment agencies to help balance the budget. Brown gets strong marks from California voters, with a public approval rating in the 60% range —impressive for an incumbent — and is the prohibitive favorite to win in November.

The governor has never been a charmer or back-slapper like his father, the late Gov. Edmund G. Brown Sr. But what some regard as hubris or intellectual high-handedness, friends and allies say is simply awkwardness. He tries reaching out a little more now than he did the last time he was governor, when overtures were rare.

By now, that effort has a familiar, somewhat stilted routine: Visitors are invited to the governor’s Capitol office, where Brown shows off a portrait of his great-grandfather, a German immigrant who came to California during the Gold Rush. He points to some rocks on his desk, taken from his family’s ranch outside the town of Williams.

But politics is always in the background.

Democratic state Sen. Kevin DeLeon of Los Angeles was wrapping up a meeting with Brown outside that history-laden office last year when the lawmaker casually expressed concern that the governor would not approve a bill widely granting driver’s licenses to immigrants in the state illegally.

“Send me the bill,” Brown fired back, “and I’ll sign it.”

With that, a years-long political log jam was broken.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.