Just how hard is it to fight a parking ticket in L.A.? Here’s one Angeleno’s story

L.A. Times Today airs Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. on Spectrum News 1.

- Share via

This is a Los Angeles story, which is one way of saying that it’s about parking. Or to be more specific, a parking ticket.

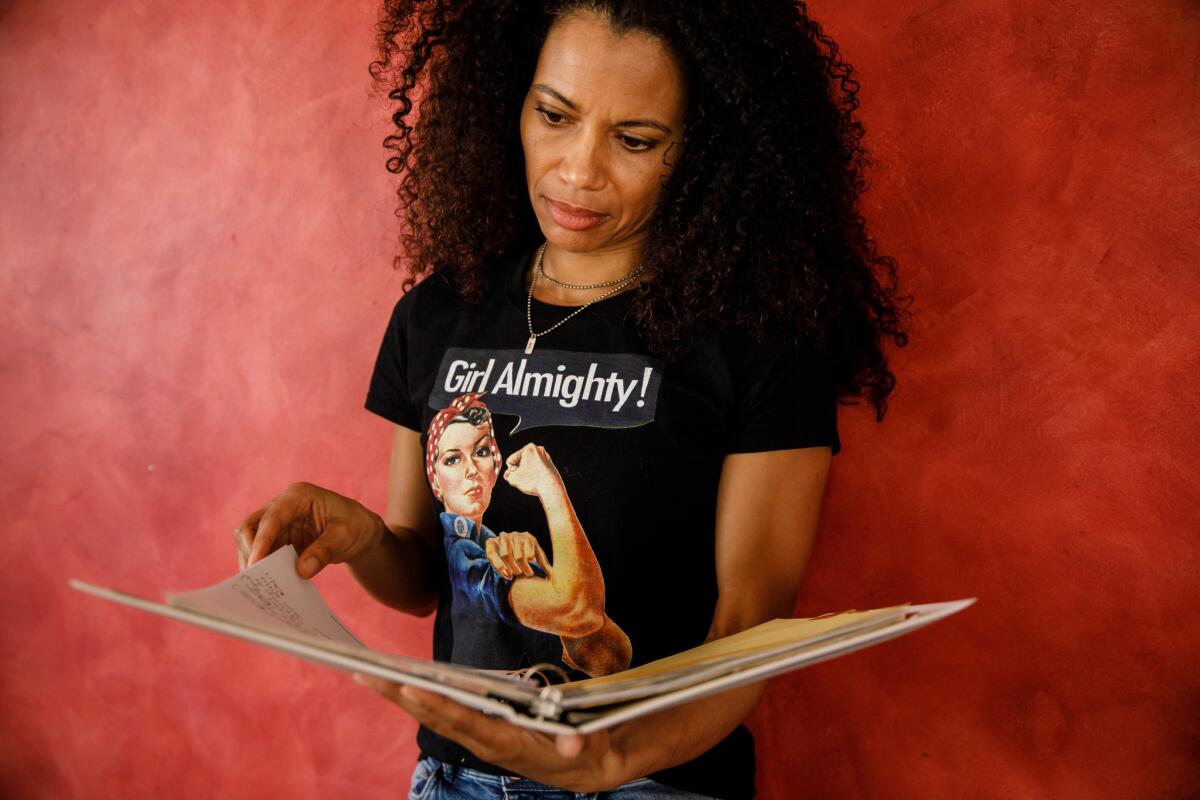

For nearly two years, Hollywood resident Lisa Soremekun fought City Hall, demanding reimbursement for the $73 parking ticket that was placed on her car — wrongly, she says — and the $239 towing fee that went with it.

The actress and filmmaker gathered affidavits from her neighbors, assembled more than a dozen court exhibits and even hired a process server to track down the city worker who caused her 2012 Ford Fiesta to be ticketed.

Soremekun, who makes much of her living appearing in television commercials, quickly learned how time-consuming, expensive and even arbitrary the city’s review process can be. But she stuck with her challenge out of a belief that the city did something wrong — ticketing and towing cars improperly, then refusing to take responsibility for what happened.

“I felt in my heart it was important to make a statement,” said Soremekun, who grew up in Toronto and goes by her stage name, Kai.

L.A. parking enforcement officers issued 2.3 million citations in the 2016-17 fiscal year, collecting nearly $141 million in ticket revenue and another $10.5 million in towing fees, according to figures provided by the city’s Department of Transportation.

Of that total, more than 46,000 parking tickets were overturned. And among those, only 165 were thrown out by a Superior Court judge, city officials said.

The seeds of Soremekun’s ordeal were planted in March 2017, when the city posted notices that crews would be resurfacing Van Ness Avenue, a quiet residential street around the corner from her one-bedroom apartment.

The city’s protocol was supposed to go like this: Street crews would post temporary no-parking signs on Van Ness at least 24 hours before construction, providing residents time to move their cars. Construction workers would pulverize the street, removing layers of deteriorating asphalt. Days or weeks later, they would come back to resurface.

In the interim, the temporary signs — placards attached with wire to trees or existing signposts — would be turned around to let residents know it was safe to park. Then, at least 24 hours before resurfacing began, the reversible signs would be turned back toward Van Ness.

Soremekun kept close watch over those signs, a habit formed from years of moving her car on street-sweeping days and for film shoots in the neighborhood. Each night, she said, the signs faced away from the street.

On the morning of April 3, 2017, Soremekun woke up to hear unsettling noises. Still in her pajamas, she ran out and saw the construction workers.

A ticket was on the windshield of her 2012 Ford Fiesta, which was already attached to a tow truck.

‘A last-minute thing’

Soremekun approached the tow truck driver first, paying him to release her car. She later tracked down Kevin Frazier, the equipment operator supervising the job. She asked him if workers had turned the reversible signs back to face Van Ness that morning.

According to Soremekun, Frazier said his workers had indeed turned the signs back that morning. Elena Stern, a spokeswoman for the city’s Bureau of Street Services, later disputed that account, telling The Times that Frazier uttered no such thing — and that the signs had been turned back a day earlier. Frazier could not be reached for comment.

Soremekun was livid. In her view, she had followed the city’s instructions. The penalties stung, too.

“I mean, that’s a car payment and some groceries,” she said. “I’m an artist and my money goes up and down. And when my money is down, and the city took $300 I could use, that’s hard.”

She wasn’t the only one saddled with expensive fines. Erin Senne, who lives down the street, said she too had been checking the signs.

“I watched every night, every single night,” said Senne, who produces events for KCRW-FM.

When Senne walked outside that April morning, her car was gone. She asked the parking enforcement officer what happened.

“She said it was a last-minute thing, that she was called out that morning and had ticketed and towed an entire block of cars,” Senne said.

The city won’t budge

Soremekun and her neighbors contacted the office of City Councilman David Ryu, who represents their neighborhood. He and an aide, Shannon Prior, were sympathetic.

With eight cars towed from the same block in a single morning, something must have gone wrong, the councilman later told The Times. His aide contacted the Bureau of Street Services, suggesting there had been a mistake. Officials in that agency disagreed, saying they followed the proper procedures.

Soremekun challenged her ticket and, after receiving a rejection in writing, filed an appeal with the city’s Department of Transportation. Because she had a flexible work schedule, she had the time to attend the city’s hearings, both of which were held in Van Nuys.

The agency scheduled the hearings on separate days — one to deal with her ticket, the other to address the towing fee.

The odds weren’t great. The year she received her citation, L.A. hearing officers, who are city employees, overturned just one out of every four parking citation appeals brought before them, according to figures provided by the city.

Soremekun struck out each time. Both hearing officers said she lacked evidence to show the temporary signs were not handled properly. But she pressed ahead.

As an entertainment industry veteran, Soremekun knew something about rejection. She had appeared in episodes of “Monk” and “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.” She was the dancing cheerleader in a McDonald’s ad and had played the wife of the jogger in a spot for Walgreens.

For every job she scored, at least a dozen auditions had produced nothing.

Soremekun filed another appeal.

A judge weighs in

With her parking ticket challenge moving out of City Hall and into Superior Court, Soremekun asked witnesses if they could sit down with a notary and support her claims in a formal affidavit. One of them was Senne, her neighbor. Another was Daniel Carson, a real estate agent living on Van Ness.

Carson had seen the temporary no-parking placards on the night before the mass towing while walking his dog.

“That night, they were still backwards,” he told The Times in an interview.

Soremekun’s big problem was Frazier, the supervisor on the Van Ness job. Although she had a process server, she still hadn’t been able to find him to summon him to testify. She asked the judge for more time.

Weeks later, while driving to the supermarket with her mother, Soremekun saw a crew doing street repairs. She pulled over to ask the supervisor about the city’s handling of temporary signs, part of her research for her upcoming court date.

To her surprise, Frazier was there.

Soremekun immediately called her process server, who showed up and handed Frazier a subpoena. The city later informed her that if she wanted him to appear, she would need to pay a $275 witness fee.

In March 2018, Soremekun finally received her day in court. By then, the odds had shifted in her favor. During that period, judges were overturning three out of every five L.A. parking tickets challenged in Superior Court.

At the hearing, Soremekun and the judge posed questions to Frazier about the temporary signs and how they were handled on Van Ness.

Frazier said city crews make sure to turn the no-parking signs toward the street a day in advance. But he noted that, because residents frequently tamper with the signs, workers sometimes have to turn them back toward the street on the day construction begins. He also said it was possible that one or two signs might have faced the wrong direction that morning.

Superior Court Judge Edward Moreton overturned the ticket, citing Frazier’s testimony.

“The witness described … how the signs get turned around by various people, and sometimes they even turn them around in the morning,” he said. “I don’t think you get fair notice of when you can and can’t park when they’re doing that.”

Soremekun emerged from the courtroom beaming. Not only had she won her case, but she had plenty of time to get to a fitting for the dog treat commercial she had landed.

Another round in court

It turned out her fight wasn’t over. Even though she had prevailed, the judge said she needed to go back to the city to get reimbursed for her witness fee and other costs.

A lawyer for City Atty. Mike Feuer received Soremekun’s request for payment weeks later and rejected it without explanation. Feuer spokesman Rob Wilcox later told The Times that Soremekun missed the deadline for filing her claim by two days.

Soremekun decided to take the city to L.A. County small claims court, demanding $634 from the city to cover her towing fee and expenses.

“Once I got my ticket reversed, I was all in,” she said.

Soremekun showed up in small claims court last summer, as did Jonathan Luevano, an investigator in Feuer’s office assigned to oppose her claim. The case was postponed to November, then January.

To prepare for the hearing, she went to court a day early to observe the judge up close.

The showdown never happened.

In the run-up to the hearing, Soremekun had asked Ryu’s deputy to serve as a witness in her case. Unbeknownst to her, another Ryu staffer — the councilman’s new chief of staff — had gotten involved. He emailed Feuer’s office the day before the hearing to say he thought the city should settle.

“Our office believes the constituent was in the right,” he wrote.

Two hours later, Feuer’s investigator called Soremekun with a straightforward offer: The city would pay her towing fee and her legal costs.

The $704 check arrived in February and the case was dismissed last month.

Soremekun was grateful to Ryu and his staff for fighting on her behalf. Yet the victory felt somewhat bittersweet.

Feuer’s team only backed down, she said, after Ryu’s last-minute intervention. Her neighbors, who paid hundreds of dollars in tickets and impound fees, never got their money back. Because the city denied wrongdoing, there hadn’t been a reckoning over the reversible signs, she said.

Officials with the Bureau of Street Services say they have been responsive. In the wake of Soremuken’s case, road repair crews have begun photographing the street on the day that repairs resume, to show the signs are facing the proper direction.

Staffers in Ryu’s office questioned whether that added step is helpful. It would make more sense, said Ryu spokesman Estevan Montemayor, for workers to take the photo the day the signs are turned toward the street, to demonstrate that residents have received proper notice.

Montemayor said his boss still worries that the city’s reliance on temporary signs, which are easily tampered with, will cause more cars to be improperly ticketed and towed. And because the process of challenging a citation is so time-consuming, most Angelenos will simply roll over and pay the penalties, he said.

“This was a very long process, and it takes a persistent person to fight through that,” Montemayor added. “Most people would just take the loss and move on, and that’s not right.”

Soremekun said she never expected her parking ticket challenge would result in nine trips to court, plus two city hearings and a one-on-one with Ryu. But she has no regrets.

“When I commit to things,” she said, “I try to see them through to the end.”

Twitter: @DavidZahniser

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.